3.3.1: Examples

- Page ID

- 2173

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Example 3.3.1.1: Beltrami Equations

\begin{eqnarray}

\label{belt1}\tag{3.3.1.1}

Wu_x-bv_x-cv_y&=&0\\

\label{belt2}\tag{3.3.1.2}

Wu_y+av_x+bv_y&=&0,

\end{eqnarray}

where \(W,\ a,\ b,\ c\) are given functions depending of \((x,y)\), \(W\not=0\) and the matrix

$$

\left(\begin{array}{cc}

a&b\\

b&c

\end{array}\right)

\]

is positive definite.

The Beltrami system is a generalization of Cauchy-Riemann equations. The function \(f(z)=u(x,y)+iv(x,y)\), where \(z=x+iy\), is called a quasiconform mapping, see for example [9], Chapter 12, for an application to partial differential equations.

Set

$$

A^1=\left(\begin{array}{cc}

W&-b\\

0&a

\end{array}\right),\ \

A^2=\left(\begin{array}{cc}

0&-c\\

W&b

\end{array}\right).

\]

Then the system (\ref{belt1}), (\ref{belt2}) can be written as

$$

A^1\left(\begin{array}{c}

u_x\\v_x

\end{array}\right)+

A^2\left(\begin{array}{c}

u_y\\v_y

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{c}0\\0\end{array}\right).

\]

Thus,

\begin{eqnarray*}

C(x,y,\zeta)=\left|\begin{array}{cc}

W\zeta_1&-b\zeta_1-c\zeta_2\\

W\zeta_2&a\zeta_1+b\zeta_2

\end{array}\right|

=W(a\zeta_1^2+2b\zeta_1\zeta_2+c\zeta_2^2),

\end{eqnarray*}

which is different from zero if \(\zeta\not=0\) according to the above assumptions. Thus the Beltrami system is elliptic.

Example 3.3.1.2: Maxwell Equations

The Maxwell equations in the isotropic case are

\begin{eqnarray}

\label{max1}\tag{3.3.1.3}

c\ \text{rot}_x\ H&=&\lambda E+\epsilon E_t\\

\label{max2}\tag{3.3.1.4}

c\ \text{rot}_x\ E&=&-\mu H_t,

\end{eqnarray}

where

- \(E=(e_1,e_2,e_3)^T\) electric field strength, \(e_i=e_i(x,t)\), \(x=(x_1,x_2,x_3)\),

- \(H=(h_1,h_2,h_3)^T\) magnetic field strength, \(h_i=h_i(x,t)\),

- \(c\) speed of light,

- \(\lambda\) specific conductivity,

- \(\epsilon\) dielectricity constant,

- \(\mu\) magnetic permeability.

Here \(c,\ \lambda,\ \epsilon\) and \(\mu\) are positive constants.

Set \(p_0=\chi_t,\ p_i=\chi_{x_i}\), \(i=1,\ldots 3\), then the characteristic differential equation is

$$

\left|\begin{array}{cccccc}

\epsilon p_0/c&0&0&0&p_3&-p_2\\

0&\epsilon p_0/c&0&-p_3&0&p_1\\

0&0&\epsilon p_0/c&p_2&-p_1&0\\

0&-p_3&p_2&\mu p_0/c&0&0\\

p_3&0&-p_1&0&\mu p_0/c&0\\

-p_2&p_1&0&0&0&\mu p_0/c

\end{array}\right|=0.

\]

The following manipulations simplifies this equation:

- multiply the first three columns with \(\mu p_0/c\),

- multiply the 5th column with \(-p_3\) and the the 6th column with \(p_2\) and add the sum to the 1st column,

- multiply the 4th column with \(p_3\) and the 6th column with \(-p_1\) and add the sum to the 2th column,

- multiply the 4th column with \(-p_2\) and the 5th column with \(p_1\) and add the sum to the 3th column,

- expand the resulting determinant with respect to the elements of the 6th, 5th and 4th row.

We obtain

$$

\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

q+p_1^2&p_1p_2&p_1p_3\\

p_1p_2&q+p_2^2&p_2p_3\\

p_1p_3&p_2p_3&q+p_3^2

\end{array}\right|=0,

\]

where

$$

q:=\frac{\epsilon\mu}{c^2}p_0^2-g^2

\]

with \(g^2:=p_1^2+p_2^2+p_3^2\). The evaluation of the above equation leads to \(q^2(q+g^2)=0\), i. e.,

$$

\chi_t^2\left(\frac{\epsilon\mu}{c^2}\chi_t^2-|\nabla_x\chi|^2\right)=0.

\]

It follows immediately that Maxwell equations are a hyperbolic system, see an exercise.

There are two solutions of this characteristic equation. The first one are characteristic surfaces \(\mathcal{S}(t)\), defined by \(\chi(x,t)=0\), which satisfy \(\chi_t=0\). These surfaces are called stationary waves The second type of characteristic surfaces are defined by solutions of

$$

\frac{\epsilon\mu}{c^2}\chi_t^2=|\nabla_x\chi|^2.

\]

Functions defined by \(\chi=f(n\cdot x-Vt)\) are solutions of this equation.

Here is \(f(s)\) an arbitrary function with \(f'(s)\not=0\), \(n\) is a unit vector and \(V=c/\sqrt{\epsilon\mu}\).

The associated characteristic surfaces \(\mathcal{S}(t)\) are defined by

$$

\chi(x,t)\equiv f(n\cdot x-Vt)=0,

\]

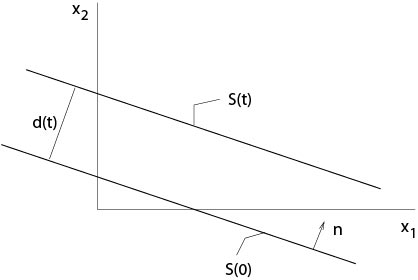

here we assume that \(0\) is in he range of \(f:\ \mathbb{R}^1\mapsto\mathbb{R}^1\). Thus, \(\mathcal{S}(t)\) is defined by \(n\cdot x-Vt=c\), where \(c\) is a fixed constant. It follows that the planes \(\mathcal{S}(t)\) with normal \(n\) move with speed \(V\) in direction of \(n\), see Figure 3.3.1.1.

Figure 3.3.1.1: \(d'(t)\) is the speed of plane waves

\(V\) is called speed of the plane wave \(\mathcal{S}(t)\).

Remark. According to the previous discussions, singularities of a solution of Maxwell equations are located at most on characteristic surfaces.

A special case of Maxwell equations are the telegraph equations, which follow from Maxwell equations if \(\text{\div}\ E=0\) and \(\text{div}\ H=0$\) i. e., \(E\) and \(H\) are fields free of sources. In fact, it is sufficient to assume that this assumption is satisfied at a fixed time \(t_0\) only, see an exercise.

Since

$$

\text{rot}_x\ \text{rot}_x\ A=\mbox{grad}_x\ \text{div}_x\ A-\triangle_xA

\]

for each \(C^2\)-vector field \(A\), it follows from Maxwell equations the uncoupled system

\begin{eqnarray*} \triangle_xE&=&\frac{\epsilon\mu}{c^2}E_{tt}+\frac{\lambda\mu}{c^2}E_t\\

\triangle_xH&=&\frac{\epsilon\mu}{c^2}H_{tt}+\frac{\lambda\mu}{c^2}H_t.

\end{eqnarray*}

Example 3.3.1.3: Equations of Gas Dynamics

Consider the following quasilinear equations of first order.

$$

v_t+(v\cdot\nabla_x)\ v+\frac{1}{\rho} \nabla_x p =f\ \ \ \mbox{(Euler equations)}.

\]

Here is

- \(v=(v_1,v_2,v_3)\) the vector of speed, \(v_i=v_i(x,t)\), \(x=(x_1,x_2,x_3)\),

- \(p\) pressure, \(p=(x,t)\),

- \(\rho\) density, \(\rho=\rho(x,t)\),

- \(f=(f_1,f_2,f_3)\) density of the external force, \(f_i=f_i(x,t)\),

\((v\cdot\nabla_x)v\equiv (v\cdot\nabla_x v_1,v\cdot\nabla_x v_2,v\cdot\nabla_x v_3))^T\).

The second equation is

$$

\rho_t+v\cdot\nabla_x\rho+\rho\ \text{div}_x\ v=0\ \ \ \mbox{(conservation of mass)}.

\]

Assume the gas is compressible and that there is a function (state equation)

$$

p=p(\rho),

\]

where \(p'(\rho)>0\) if \(\rho>0\). Then the above system of four equations is

\begin{eqnarray}

\label{euler}\tag{3.3.1.5}

v_t+(v\cdot\nabla)v+\frac{1}{\rho}p'(\rho)\nabla\rho&=&f\\

\label{cont}\tag{3.3.1.6}

\rho_t+ \rho\ \text{div}\ v+v\cdot\nabla\rho&=&0,

\end{eqnarray}

where \(\nabla\equiv\nabla_x\) and \(\text{div}\equiv\text{div}_x\), i. e., these operators apply on the spatial variables only.

The characteristic differential equation is here

$$

\left|\begin{array}{cccc}

\frac{d\chi}{dt}&0&0&\frac{1}{\rho}p'\chi_{x_1}\\

0&\frac{d\chi}{dt}&0&\frac{1}{\rho}p'\chi_{x_2}\\

0&0&\frac{d\chi}{dt}&\frac{1}{\rho}p'\chi_{x_3}\\

\rho\chi_{x_1}& \rho\chi_{x_2}&\rho\chi_{x_3}&\frac{d\chi}{dt}

\end{array}\right|=0,

\]

where

$$\dfrac{d\chi}{dt}:=\chi_t+(\nabla_x\chi)\cdot v. \]

Evaluating the determinant, we get the characteristic differential equation

\begin{equation}

\label{chargas}\tag{3.3.1.7}

\left(\frac{d\chi}{dt}\right)^2\left(\left(\frac{d\chi}{dt}\right)^2-p'(\rho)|\nabla_x\chi|^2\right)=0.

\end{equation}

This equation implies consequences for the speed of the characteristic surfaces as the following consideration shows.

Consider a family \(\mathcal{S}(t)\) of surfaces in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) defined by \(\chi(x,t)=c\), where

\(x\in\mathbb{R}^3 \) and \(c\) is a fixed constant. As usually, we assume that \(\nabla_x\chi\not=0\).

One of the two normals on \(\mathcal{S}(t)\) at a point of the surface \(\mathcal{S}(t)\) is given by, see an exercise,

\begin{equation}

\label{surfnormal}\tag{3.3.1.8}

{\bf n}=\frac{\nabla_x\chi}{|\nabla_x\chi|}.

\end{equation}

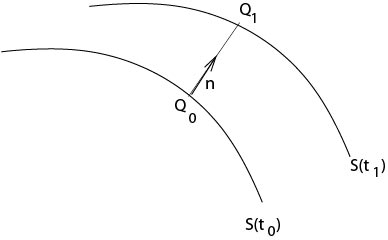

Let \(Q_0\in\mathcal{S}(t_0)\) and let \(Q_1\in\mathcal{S}(t_1)\) be a point on the line defined by \(Q_0+s{\bf n}\), where \({\bf n}\) is the normal (\ref{surfnormal}) on \(\mathcal{S}(t_0)\) at \(Q_0\) and \(t_0<t_1\), \(t_1-t_0\) small, see Figure 3.3.1.2.

3.3.1.2: Definition of the speed of a surface

Definition. The limit

$$

P=\lim_{t_1\to t_0}\frac{|Q_1-Q_0|}{t_1-t_0}

$$

is called speed of the surface \(\mathcal{S}(t)\).

Proposition 3.2. The speed of the surface \(\mathcal{S}(t)\) is

\begin{equation}

\label{speedsurf}

P=-\frac{\chi_t}{|\nabla_x\chi|}.

\end{equation}

Proof. The proof follows from \(\chi(Q_0,t_0)=0\) and \(\chi(Q_0+d{\bf n},t_0+\triangle t)=0\), where \(d=|Q_1-Q_0|\) and \(\triangle t=t_1-t_0\).

\(\Box\)

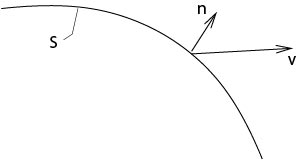

Set \(v_n:=v\cdot{\bf n}\) which is the component of the velocity vector in direction \({\bf n}\).

From ({\ref{surfnormal}) we get

$$

v_n=\frac{1}{|\nabla_x\chi|}v\cdot \nabla_x\chi.

\]

Definition. \(V:=P-v_n\), the difference of the speed of the surface and the speed of liquid particles, is called relative speed.

Figure 3.3.1.3: Definition of relative speed

Using the above formulas for \(P\) and \(v_n\) it follows

$$

V=P-v_n=-\frac{\chi_t}{|\nabla_x\chi|}-\frac{v\cdot\nabla_x\chi}{|\nabla_x\chi|}=-\frac{1}{|\nabla_x\chi|}\frac{d\chi}{dt}.

$$

Then, we obtain from the characteristic equation (\ref{chargas}) that

$$

V^2|\nabla_x\chi|^2\left(V^2|\nabla_x\chi|^2-p'(\rho)|\nabla_x\chi|^2\right)=0.

$$

An interesting conclusion is that there are two relative speeds: \(V=0\) or \(V^2=p'(\rho)\).

Definition. \(\sqrt{p'(\rho)}\) is called speed of sound.

Contributors and Attributions

Integrated by Justin Marshall.