4.4: Vectors, Lists and Functions- \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\)

- Page ID

- 1864

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

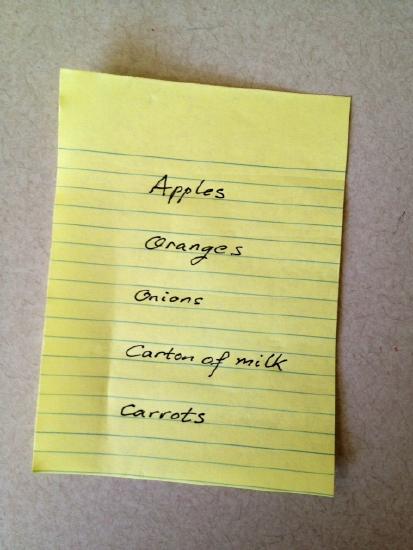

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Suppose you are going shopping. You might jot down something like this on a piece of paper:

We could represent this information mathematically as a set, $$S=\{\rm apple, orange, onion, milk, carrot\}\, .\]

There is no information of ordering here and no information about how many carrots you will buy. This set by itself is not a vector; how would we add such sets to one another?

If you were a more careful shopper your list might look like this:

What you have really done here is assign a number to each element of the set \(S\). In other words, the second list is a function

$$

f:S\longrightarrow {\mathbb R}\, .

$$

Given two lists like the second one above, we could easily add them -- if you plan to buy 5 apples and I am buying 3 apples, together we will buy 8 apples! In fact, the second list is really a 5-vector in disguise.

In general it is helpful to think of an \(n\)-vector as a function whose domain is the set \(\{1,\dots,n\}\). This is equivalent to thinking of an \(n\)-vector as an ordered list of \(n\) numbers. These two ideas give us two equivalent notions for the set of all \(n\)-vectors:

$$

{\mathbb{R}}^{n} :=\left\{ \begin{pmatrix}a^{1} \\ \vdots \\ a^{n}\end{pmatrix} \middle\vert \, a^{1},\dots a^{n} \in \mathbb{R} \right\}

=\{ a:\{1,\dots,n\}\to \mathbb{R}\} := \mathbb{R}^{ \{1,\cdots,n\} }

$$

The notation \(\mathbb{R}^{ \{1,\cdots,n\} }\) is used to denote functions from \(\{1,\dots,n\}\) to \(\mathbb{R}\). Similarly, for any set \(S\) the notation \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\) denotes the set of functions from \(S\) to \(\mathbb{R}\):

$$

\mathbb{R}^{S}:=\{ f:S\to \mathbb {R}\}\, .

$$

When \(S\) is an ordered set like \(\{1,\dots,n\}\), it is natural to write the components in order. When the elements of \(S\) do not have a natural ordering, doing so might cause confusion.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Consider the set \(S=\{*, \star, \# \}\) from chapter 1 review problem 9. A particular element of \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\) is the function \(a\) explicitly defined by

$$ a^{\star}=3, a^{\#}=5, a^{*}=-2.$$

It is not natural to write

$$

a=\begin{pmatrix}3 \\ 5 \\ -2\end{pmatrix} ~{\rm or} ~a=\begin{pmatrix}-2\\ 3 \\ 5\end{pmatrix}

$$

because the elements of \(S\) do not have an ordering, since as sets \(\{*, \star, \# \}=\{*,\star,\#\}\).

In this important way, \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\) seems different from \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\). What is more evident are the similarities; since we can add two functions, we can add two elements of \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\):

Addition in \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\)

If \(a^{\star}=3, a^{\#}=5, a^{*}=-2\) and \(b^{\star}=-2, b^{\#}=4, b^{*}=13\)

then \(a+b\) is the function

$$(a+b)^{\star}=3-2=1, (a+b)^{\#}=5+4=9, (a+b)^{*}=-2+13=11\, .\]

Also, since we can multiply functions by numbers, there is a notion of scalar multiplication on \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\):

Scalar Multiplication in \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\)

If \(a^{\star}=3, a^{\#}=5, a^{*}=-2\),

then \(3a\) is the function

$$(3a)^{\star}=3\cdot3=9, (3a)^{\#}=3\cdot5=15, (3a)^{*}=3(-2)=-6\, .\]

We visualize \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) and \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) in terms of axes. We have a more abstract picture of \(\mathbb{R}^{4}\), \(\mathbb{R}^{5}\) and \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\) for larger \(n\) while \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\) seems even more abstract. However, when thought of as a simple "shopping list'', you can see that vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^{S}\) in fact, can describe everyday objects. In chapter 5 we introduce the general definition of a vector space that unifies all these different notions of a vector.

Contributor

David Cherney, Tom Denton, and Andrew Waldron (UC Davis)