8.5: Continuous Real Functions

- Page ID

- 100751

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In this section, we will explore the concept of continuity, which you likely encountered in high school.

Definition 8.95. A real function is any function \(f:A\to \mathbb{R}\) such that \(A\) is a nonempty subset of \(\mathbb{R}\).

There are several equivalent definitions of continuity for real functions. The following characterization is typically referred to as the epsilon-delta definition of continuity. Our definition mimics the definition of continuity used in metric spaces, which \(\mathbb{R}\) equipped with absolute value happens to be an example of. Recall that \(|a-b|<r\) means that the distance between \(a\) and \(b\) is less than \(r\) (see discussion below Corollary 5.31).

Definition 8.96. Suppose \(f\) is a real function such that \(a\in dom(f)\). We say that \(f\) is continuous at \(a\) if for every \(\varepsilon>0\), there exists \(\delta>0\) such that if \(x\in dom(f)\) and \(|x-a|<\delta\), then \(|f(x)-f(a)|<\varepsilon\). If \(f\) is continuous at every point in \(B\subseteq dom(f)\), then we say that \(f\) is continuous on \(B\). If \(f\) is continuous on its entire domain, we simply say that \(f\) is continuous.

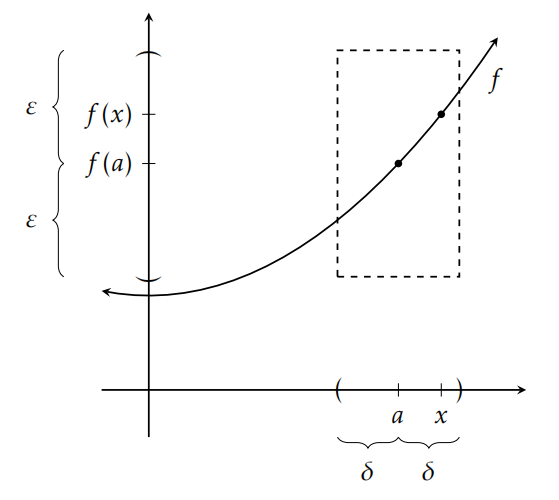

Loosely speaking, a real function \(f\) is continuous at the point \(a\in dom(f)\) if we can get \(f(x)\) arbitrarily close to \(f(a)\) by considering all \(x\in dom(f)\) sufficiently close to \(a\). The value \(\varepsilon\) is indicating how close to \(f(a)\) we need to be while the value \(\delta\) is providing the “window" around \(a\) needed to guarantee that all points in the window (and in the domain) yield outputs within \(\varepsilon\) of \(f(a)\). Figure 8.5 illustrates our definition of continuity. Note that in the figure, the point \(a\) is fixed while we need to consider all \(x\in dom(f)\) such that \(|x-a|<\delta\). The dashed box in the figure has dimensions \(2\delta\) by \(2\varepsilon\) and is centered at the point \((a,f(a))\). Intuitively, the function is continuous at \(a\) since given \(\varepsilon>0\), we could find \(\delta >0\) so that the graph of the function never exits the top or bottom of the dashed box.

Perhaps you have encountered the phrase “a function is continuous if you can draw its graph without lifting your pencil." While this description provides some intuition about what continuity of a function means, it is neither accurate nor precise enough to capture the meaning of continuity.

When proving that a function is continuous at a point, the choice of \(\delta\) depends on both the point in question and the value of \(\varepsilon\). An example should be helpful.

Example 8.97. Define \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) via \(f(x)=3x+2\). Let’s prove that \(f\) is continuous (at every point in the domain). Let \(a\in\mathbb{R}\) and let \(\varepsilon>0\). Choose \(\delta=\varepsilon/3\). We will see in a moment why this is a good choice for \(\delta\). Suppose \(x\in\mathbb{R}\) such that \(|x-a|<\delta\). We see that \[|f(x)-f(a)|=|(3x+2)-(3a+2)|=|3x-3a| = 3\cdot |x-a|<3\cdot \delta = 3\cdot \varepsilon/3 =\varepsilon.\] We have shown that \(f\) is continuous at \(a\), and since \(a\) was arbitrary, \(f\) is continuous.

Problem 8.98. Prove that each of the following real functions is continuous using Definition 8.96.

- \(f:\mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}\) defined via \(f(x)=x\).

- \(g:\mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}\) defined via \(g(x)=x+42\).

- \(h:\mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}\) defined via \(h(x)=5x\).

The next result tells us that every linear real function is continuous. Do not forget to handle the case when \(m=0\) in your proof. Note that the case when \(m=0\) proves that every constant function is continuous.

Theorem 8.99. If \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) is defined via \(f(x)=mx+b\) for \(m,b\in\mathbb{R}\), then \(f\) is continuous.

The second part of the next problem is much harder than you might expect.

Problem 8.100. Define \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) via \(f(x)=x^2\).

- Prove that \(f\) is continuous at 0.

- Prove that \(f\) is continuous at 1.

Problem 8.101. Define \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) via \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\). Prove that \(f\) is continuous at 0.

Problem 8.102. Suppose \(f\) is a real function. Write a precise statement for what it means for \(f\) to not be continuous at \(a\in dom(f)\).

Problem 8.103. Define \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) via \[f(x)=\begin{cases} 1, & \text{if }x=0\\ x, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases}\] Determine where \(f\) is continuous and justify your assertion.

Problem 8.104. Define \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) via \[f(x)=\begin{cases} 1, & \text{if }x\in \mathbb{Q}\\ 0, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases}\] Determine where \(f\) is continuous and justify your assertion.

After completing the next problem, reflect on the statement “a function is continuous if you can draw its graph without lifting your pencil."

Problem 8.105. Define \(f:\mathbb{N}\to\mathbb{R}\) via \(f(x)=1\). Notice the domain! Determine where \(f\) is continuous and justify your assertion.

Theorem 8.106. Suppose \(f\) is a real function. Then \(f\) is continuous if and only if the preimage \(f^{-1}(U)\) of every open set \(U\) is an open set intersected with the domain of \(f\).

The previous characterization of continuity is often referred to as the “open set definition of continuity," although for us it is a theorem instead of a definition. This is the definition used in topology. Another notion of continuity, called “sequential continuity", makes use of convergent sequences. All of these characterizations of continuity are equivalent for the real numbers (using the standard definition of an open set). However, there are contexts in mathematics where the epsilon-delta definition of continuity is undefined (because there is not a notion of distance in either the domain or codomain) and others where continuity and sequential continuity are not equivalent.

Since every open set is the union of bounded open intervals (Definition 5.53), the union of open sets is open (Theorem 5.58), and preimages respect unions (Theorem 8.92), we can strengthen Theorem 8.106 into a slightly more useful result.

Theorem 8.107. Suppose \(f\) is a real function. Then \(f\) is continuous if and only if the preimage \(f^{-1}(I)\) of every bounded open interval \(I\) is an open set intersected with the domain of \(f\).

Now that we have two methods for verifying continuity (Definition 8.96 and Theorem 8.106/8.107), you can use either one when approaching the remaining problems in this section. Sometimes it does not matter which approach you take and other times one method might be better suited to the task.

Problem 8.108. Define \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) via \(f(x)=x^2\). Prove that \(f\) is continuous.

Problem 8.109. Define \(f:\mathbb{R}\setminus\{0\}\to\mathbb{R}\) via \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\). Determine where \(f\) is continuous and justify your assertion.

The previous problems once again calls into question the phrase “a function is continuous if you can draw its graph without lifting your pencil."

Problem 8.110. Find a continuous real function \(f\) and an open interval \(I\) such that the preimage \(f^{-1}(I)\) is not an open interval.

For the next few problems, if you attempt to construct counterexamples, you may rely on your previous knowledge about various functions that you encountered in high school and calculus.

Problem 8.111. Suppose \(f\) is a continuous real function. If \(U\) is an open set contained in \(dom(f)\), is the image \(f(U)\) always open? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.

Problem 8.112. Suppose \(f\) is a continuous real function. If \(C\) is a closed set, is the preimage \(f^{-1}(C)\) always a closed set? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.

Problem 8.113. Suppose \(f\) is a continuous real function. If \([a,b]\) is a closed interval contained in \(dom(f)\), is the image \(f([a,b])\) always a closed interval? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.

Problem 8.114. Suppose \(f\) is a continuous real function. If \(C\) is a closed set contained in \(dom(f)\), is the image \(f(C)\) always a closed set? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.

Problem 8.115. Suppose \(f\) is a continuous real function. If \(B\) is bounded set contained in \(dom(f)\), is the image \(f(B)\) always a bounded set? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.

Problem 8.116. Suppose \(f\) is a continuous real function. If \(B\) is a bounded set, is the preimage \(f^{-1}(B)\) always a bounded set? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.

Problem 8.117. Suppose \(f\) is a continuous real function. If \(K\) is a compact set, is the preimage \(f^{-1}(B)\) always a compact set? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.

Problem 8.118. Suppose \(f\) is a continuous real function. If \(C\) is a connected set contained in \(dom(f)\), is the image \(f(C)\) always connected? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.

Problem 8.119. Suppose \(f\) is a continuous real function. If \(C\) is a connected set, is the preimage \(f^{-1}(C)\) always a connected set? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.

Perhaps you noticed the absence of one natural question in the previous sequence of problems. If \(f\) is a continuous real function and \(K\) is a subset of the domain of \(f\), is the image \(f(K)\) a compact set? It turns out that the answer is “yes", but proving this fact is beyond the scope of this book. This theorem is often proved in a real analysis course and is then used to prove the Extreme Value Theorem, which you may have encountered in your calculus course.

The next result is a special case of the well-known Intermediate Value Theorem, which states that if \(f\) is a continuous real function whose domain contains the interval \([a,b]\), then \(f\) attains every value between \(f(a)\) and \(f(b)\) at some point within the interval \([a,b]\). To prove the special case, utilize Theorem 5.87 and Problem 8.118 together with a proof by contradiction.

Theorem 8.120. Suppose \(f\) is a real function. If \(f\) is continuous on \([a,b]\) such that \(f(a)<0<f(b)\) or \(f(a)>0>f(b)\), then there exists \(r\in [a,b]\) such that \(f(r)=0\).

If we generalize the previous result, we obtain the Intermediate Value Theorem.

Theorem 8.121. Suppose \(f\) is a real function. If \(f\) is continuous on \([a,b]\) such that \(f(a)<c<f(b)\) or \(f(a)>c>f(b)\) for some \(c\in \mathbb{R}\), then there exists \(r\in [a,b]\) such that \(f(r)=c\).

Problem 8.122. Is the converse of the Intermediate Value Theorem true? If so, prove it. Otherwise, provide a counterexample.