9.4: Countable Sets

- Page ID

- 95463

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Recall that if \(A=\emptyset\), then we say that \(A\) has cardinality 0. Also, if \(card(A)=card([n])\) for \(n\in\mathbb{N}\), then we say that \(A\) has cardinality \(n\). We have a special way of describing sets that are in bijection with the natural numbers.

Definition 9.36. If \(A\) is a set such that \(card(A)=card(\mathbb{N})\), then we say that \(A\) is denumerable and has cardinality \(\mathbf{\aleph_0}\) (read “aleph naught").

Notice if a set \(A\) has cardinality \(1,2,\ldots\), or \(\aleph_0\), we can label the elements in \(A\) as “first", “second", and so on. That is, we can “count" the elements in these situations. Certainly, if a set has cardinality 0, counting is not an issue. This idea leads to the following definition.

Definition 9.37. A set \(A\) is called countable if \(A\) is finite or denumerable. A set is called uncountable if it is not countable.

Problem 9.38. Quickly justify that each of the following sets is countable. Feel free to appeal to previous problems. Which sets are denumerable?

- \(\{a,b,c\}\)

- Set of odd natural numbers

- Set of even natural numbers

- \(\{\frac{1}{2^n}\mid n\in \mathbb{N}\}\)

- Set of perfect squares in \(\mathbb{N}\)

- \(\mathbb{Z}\)

- \(\mathbb{N}\times \{a\}\)

Utilize Theorem 9.31 or Corollary 9.33 when proving the next result.

Theorem 9.39. Every infinite set contains a denumerable subset.

Theorem 9.40. Let \(A\) and \(B\) be sets such that \(A\) is countable. If \(f:A\to B\) is a bijection, then \(B\) is countable.

For the next proof, consider the cases when \(A\) is finite versus infinite. The contrapositive of Corollary 9.32 should be useful for the case when \(A\) is finite.

Theorem 9.41. Every subset of a countable set is countable.

Theorem 9.42. A set is countable if and only if it has the same cardinality of some subset of the natural numbers.

Theorem 9.43. If \(f:\mathbb{N}\to A\) is a surjective function, then \(A\) is countable.

Loosely speaking, the next theorem tells us that we can arrange all of the rational numbers then count them “first", “second", “third", etc. Given the fact that between any two distinct rational numbers on the number line, there are an infinite number of other rational numbers (justified by taking repeated midpoints), this may seem counterintuitive.

Here is one possible approach for proving the next theorem. Make a table with column headings \(0, 1, -1, 2,-2,\ldots\) and row headings \(1,2,3,4,5,\ldots\). If a column has heading \(m\) and a row has heading \(n\), then the entry in the table corresponds to the fraction \(m/n\). Find a way to zig-zag through the table making sure to hit every entry in the table (not including column and row headings) exactly once. This justifies that there is a bijection between \(\mathbb{N}\) and the entries in the table. Do you see why? But now notice that every rational number appears an infinite number of times in the table. Resolve this by appealing to Theorem 9.41.

Theorem 9.44. The set of rational numbers \(\mathbb{Q}\) is countable.

Theorem 9.45. If \(A\) and \(B\) are countable sets, then \(A\cup B\) is countable.

We would like to prove a stronger result than the previous theorem. To do so, we need an intermediate result.

Theorem 9.46. Let \(\{A_n\}_{n=1}^{\infty}\) be a collection of sets. Define \(B_1:= A_1\) and for each natural number \(n>1\), define \[B_n:= A_n\setminus \bigcup_{i=1}^{n-1}A_i.\] Then we we have the following:

- The collection \(\{B_n\}_{n=1}^{\infty}\) is pairwise disjoint.

- \(\displaystyle \bigcup_{n=1}^{\infty}A_n =\bigcup_{n=1}^{\infty}B_n\).

The next theorem states that the union of a countable collection of countable sets is countable. To prove this, consider two cases:

- The collection of sets is finite.

- The collection of sets is infinite.

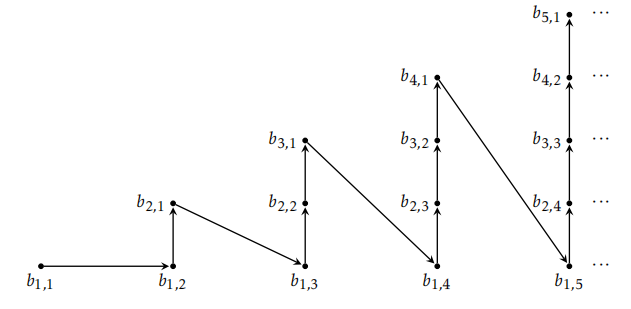

To handle the first case, use induction together with Theorem 9.45. The second case is substantially more challenging. First, use Theorem 9.46 to construct a collection \(\{B_n\}\) of pairwise disjoint sets whose union is equal to the union of the original collection. Since each \(B_n\) is a subset of one of the sets in the original collection and each of these sets is countable, each \(B_n\) is also countable by Theorem 9.41. This implies that for each \(n\), we can write \(B_n=\{b_{n,1}, b_{n,2},b_{n,3},\ldots\}\), where the set may be finite or infinite. From here, we outline two different approaches for continuing. One approach is to construct a bijection from \(\mathbb{N}\) to \(\bigcup_{n=1}^{\infty}B_n\) using Figure 9.2 as inspiration. One thing you will need to address is what to do when a set in the collection \(\{B_n\}\) is finite. For the second approach, define \(f:\bigcup_{n=1}^{\infty}B_n\to \mathbb{N}\) via \(f(b_{n,m})=2^n3^m\), verify that this function is injective, and then appeal to Theorem 9.41. Try using both of these approaches when tackling the proof of the following theorem.

= [circle, draw, fill=black,inner sep=0pt, minimum size=.7mm]

Theorem 9.47. Let \(\Delta\) be equal to either \(\mathbb{N}\) or \([k]\) for some \(k\in\mathbb{N}\). If \(\{A_n\}_{n\in\Delta}\) is a countable collection of sets such that each \(A_n\) is countable, then \(\bigcup_{n\in \Delta}A_n\) is countable.

Do you use the Axiom of Choice when proving the previous theorem? If so, where?

Theorem 9.48. If \(A\) and \(B\) are countable sets, then \(A\times B\) is countable.

Theorem 9.49. The set of all finite sequences of 0’s and 1’s (e.g., \(0110010\) is a finite sequence consisting of 0’s and 1’) is countable.

Theorem 9.50. The collection of all finite subsets of a countable set is countable.