4.2: Interval Notation

- Page ID

- 83128

Inequalities slice and dice the real number line into segments of interest or intervals. An interval is a continuous, uninterrupted subset of real numbers. How can we notate intervals with simplicity? The table below introduces Interval Notation.

| Inequality | Associated Circle | Associated Endpoint Closures |

|---|---|---|

|

Either \(<\) or \(>\) |

|

Left Parenthesis: ( or Right Parenthesis: ) |

|

Either \(≤\) or \(≥\) |

|

Left Square bracket: [ or Right Square Bracket: ] |

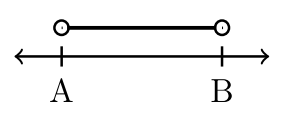

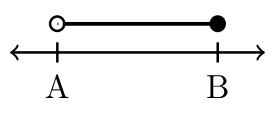

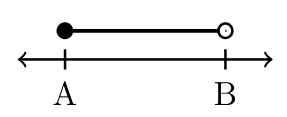

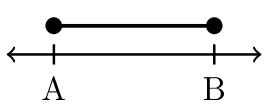

Inequalities have \(4\) possible interval closures:

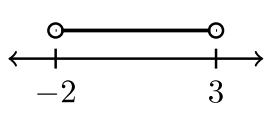

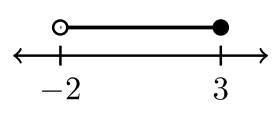

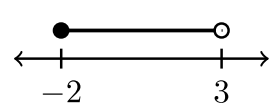

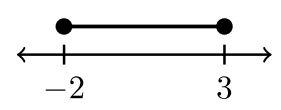

| \((A,B)\) | \((A,B]\) | \([A,B)\) | \([A,B]\) |

|

|

|

|

|

The least number in the interval, \(A\), is always stated first. A comma is placed. The largest number in the interval, \(B\), is stated after the comma. The appropriate closure is considered for each value \(A\) and \(B\).

Four Examples of Interval Notation

| \(−2 < x < 3\) | \(−2 < x ≤ 3\) | \(– 2 ≤ x < 3\) | \(– 2 ≤ x ≤ 3\) |

|

|

|

|

|

| \((−2, 3)\) | \((−2, 3]\) | \([−2, 3)\) | \([−2, 3]\) |

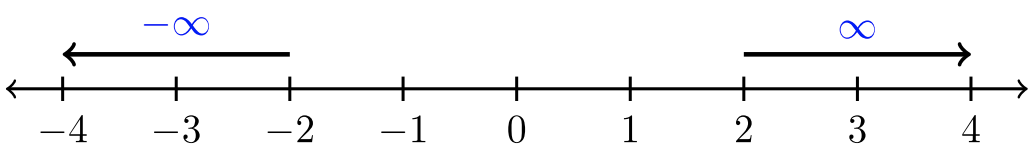

The Infinities

There are two infinities: positive and negative. Each define a direction on the number line:

Infinity is not a real number. It indicates a direction. Therefore, when using interval notation, always enclose \(∞\) and \(−∞\) with parenthesis. We never enclose infinities with square bracket.

The table below shows four examples of interval notation that require the use of infinity.

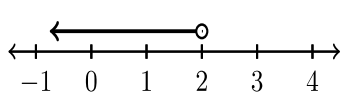

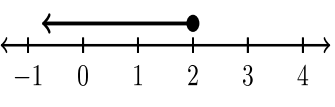

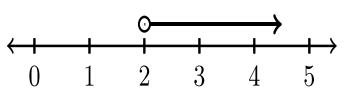

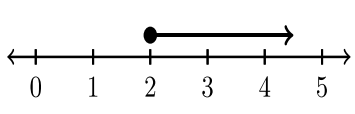

| \(x < 2\) | \(x ≤ 2\) | \(x > 2\) | \(x ≥ 2\) |

|

|

|

|

|

| \((−∞, 2)\) | \((−∞, 2]\) | \((2, ∞)\) | \([2, ∞)\) |

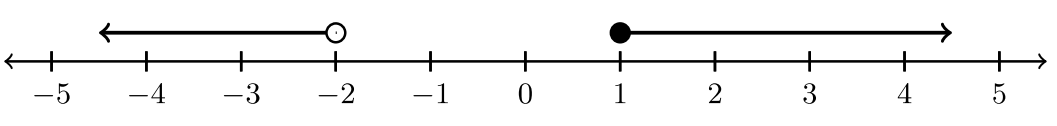

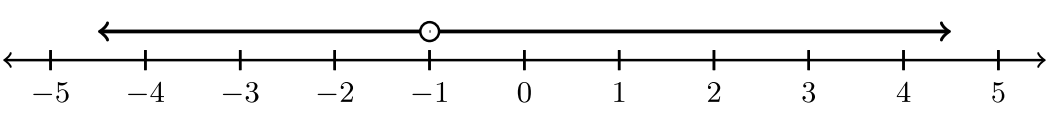

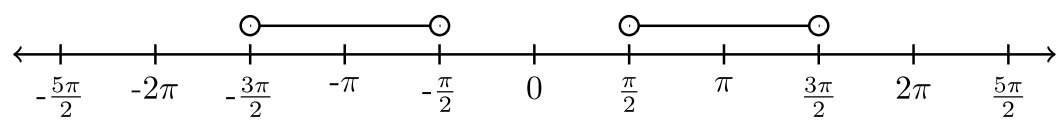

Combinations of Intervals

If two or more intervals are interrupted with a gap in the number line, set notation is used to stitch the intervals together, symbolically. The symbol we use to combine intervals is the union symbol: \(∪\). The table below shows four examples:

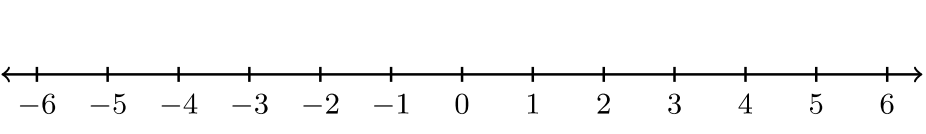

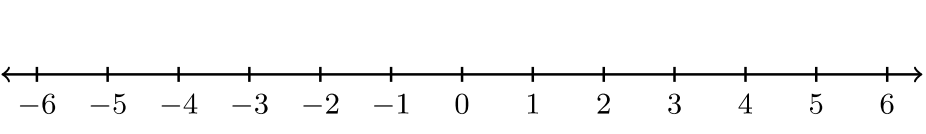

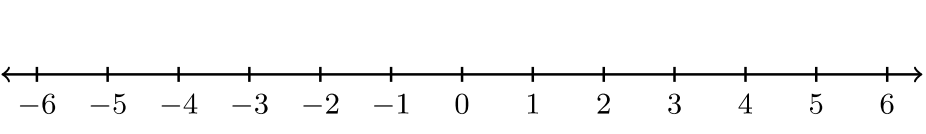

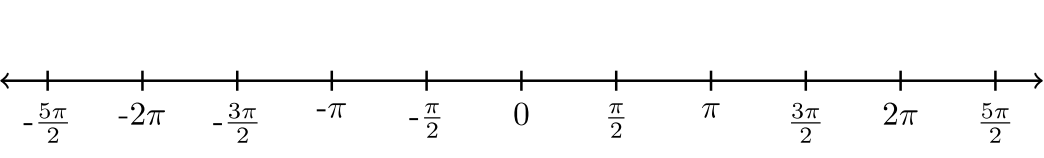

| Interval Notation | Graph | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| \((−∞, −2) ∪ [1, ∞)\) |  |

||

| \((−∞, −1) ∪ (−1, ∞)\) |  |

||

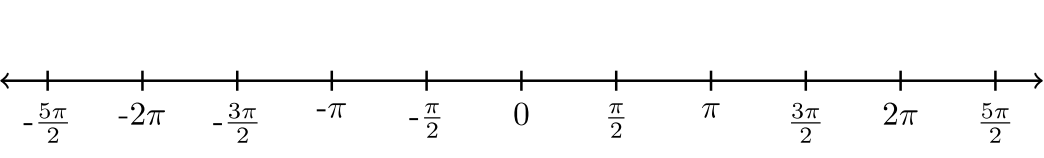

| \(\left(−\dfrac{3 \pi}{2} , −\dfrac{\pi}{2} \right) ∪ \left( \dfrac{\pi}{2}, \dfrac{3 \pi}{2} \right)\) |  |

||

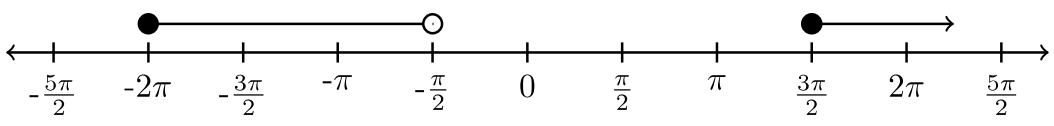

| \(\left[−2 \pi, − \dfrac{\pi}{2} \right) ∪ \left[ \dfrac{3 \pi}{2} , ∞ \right)\) |  |

||

Compound Inequalities

Intervals that have gaps, like the ones shown above, translate to compound inequalities. Real solutions belong in one interval or another. The word “or” plays a key role when translating. For example: the interval \((−∞, −2) ∪ [1, ∞)\) translates to its associated compound inequality:

\(x < -2\) or \(x ≥ 1\)

The word “and” cannot be used between the inequalities because a number cannot belong to both intervals at once. For example, \(x = 5\) is a solution because \(5\) belongs in the interval \(x ≥ 1\), but \(5\) does not belong in the interval \(x < −2\). Nevertheless, because of the word “or,” \(x = 5\) is a solution to the interval \((−∞, −2) ∪ [1, ∞)\).

Try It! (Exercises)

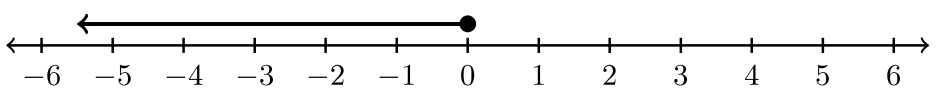

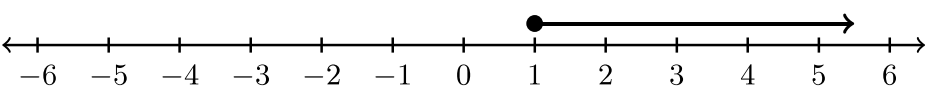

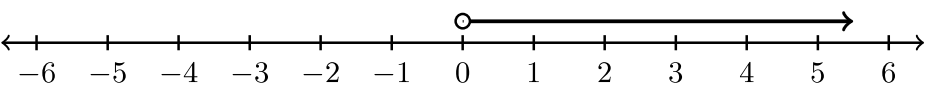

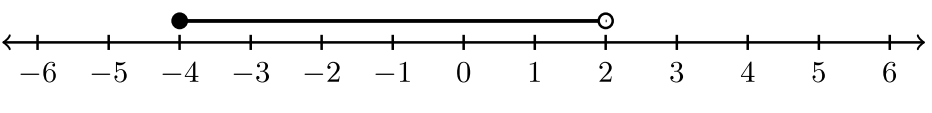

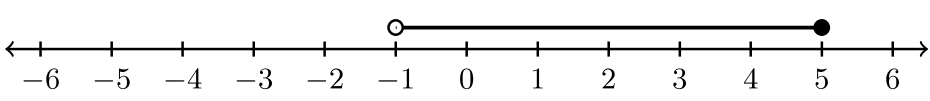

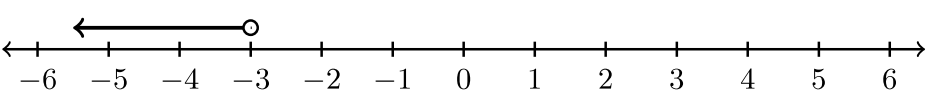

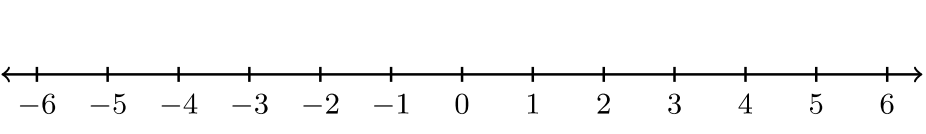

For exercises #1-6, state the inequality and the interval notation associated with the graph.

| Graph | Inequality | Interval Notation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

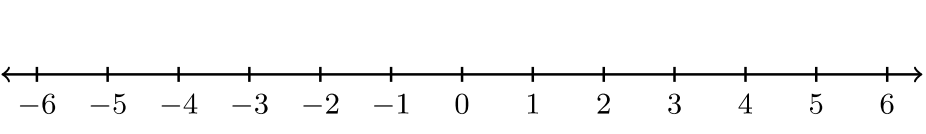

For exercises #7-10, state the interval notation and sketch the graph associated with the inequality.

| Graph | Inequality | Interval Notation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

\(−3 ≤ x ≤ 1\) | |||

|

\(x < 4\) | |||

|

\(x ≥ −2\) | |||

|

\(0 ≤ x < 3\) | |||

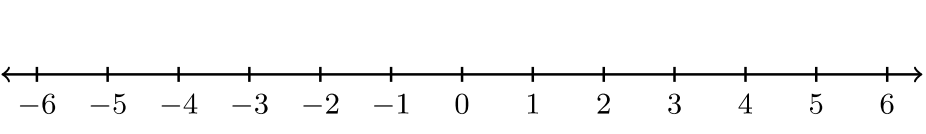

For exercises #11-17, sketch the graph associated with the given interval notation.

| Graph | Interval Notation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

\((−∞, 4)\) | ||

|

\((−∞, −3) ∪ [0, ∞)\) | ||

|

\([−1, 1) ∪ [2, ∞)\) | ||

|

\((−∞, −5] ∪ (−1, 5)\) | ||

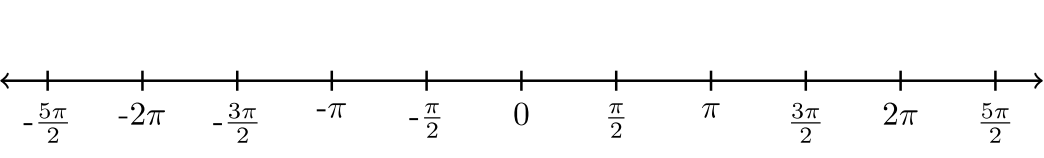

|

\(\left[−\dfrac{\pi}{2} , \dfrac{\pi}{2} \right]\) | ||

|

\((−∞, −\pi] ∪ [\pi, ∞)\) | ||

|

\(\left(−\dfrac{3\pi}{2} , −\dfrac{\pi}{2} \right) ∪ \left(-\dfrac{\pi}{2} , 0\right)\) | ||

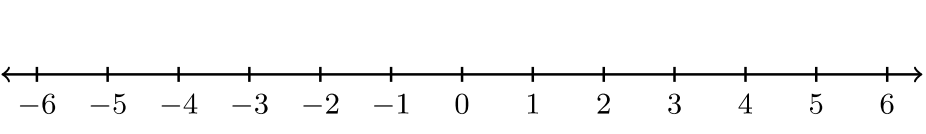

For #18-21

a. Sketch a graph of the compound inequality.

b. State the interval using interval notation.

- \(x ≥ 4\) or \(x ≤ 0\)

- \(x ≤ – 2\pi\) or \(x > \pi\)

- \(−1 > x\) or \(2 ≤ x\)

- \(x > 3\pi\) or \(x < – \pi\)