3.2: Critical points and Fatou theorem

- Page ID

- 101394

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

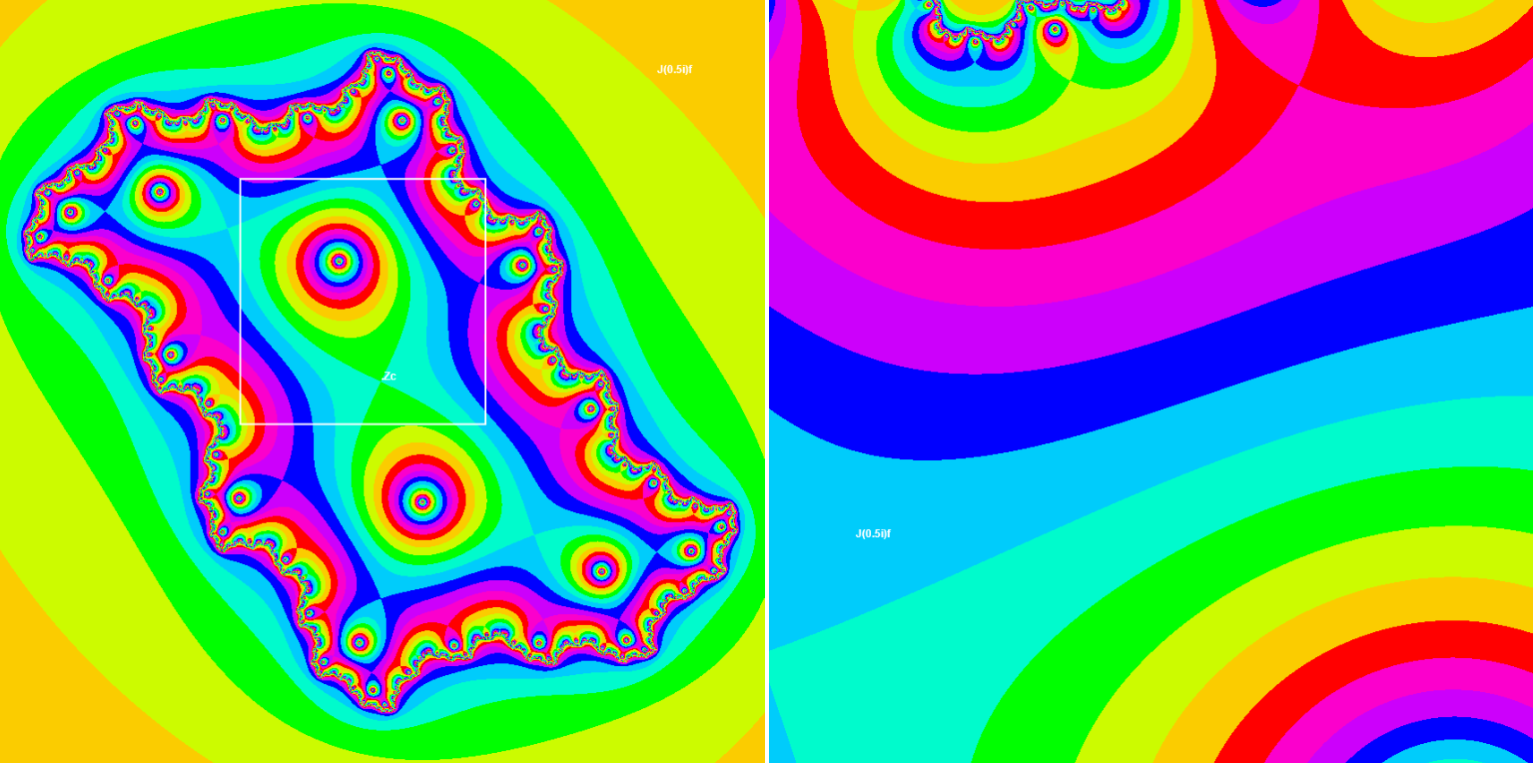

The orbit starting at zo = 0 which converges to the attracting fixed point z∗ = f(z∗ ) is shown to the left. For small ε

fc(z∗ + ε ) = z∗ + λ ε + O(ε 2), |λ| < 1

therefore f maps every disk with radius R into the next smaller one with radius |λ|R (really the "circles" are distorted a little by the O(ε 2) terms).

You see these small circles around the attracting fixed points below (here |λ| = 0.832). One of two branches of the inverse function f -1(z) maps the disks vice versa. We can extend the map analytically, while f -1(z) is a smooth nonsingular function with finite derivative [1].

Differentiating f -1(f(z)) = z we get

f -1(t)'|t = f(z) = 1 / f '(z).

Therefore the map is singular if f '(z) = 0. Points zc for which f '(zc ) = 0 are called critical points of a map f. E.g. quadratic map fc(z) = z2 + c with derivative fc(z)' = 2z has the only critical point zc = 0 and inverse function fc-1(z) = ±(z - c)½ is singular at z = c. We can continue fc-1 up to the outside border of the yellow region.

The border contains the point z = c and is mapped on the figure eight curve with the critical point zc in the center. Therefore iterations fcon(zc ) converge to z∗ for large n (the orbit is called the critical orbit). This is the subject of the Fatou theorem.

Fatou theorem: every attracting cycle for a polynomial or rational function attracts at least one critical point.

As since quadratic maps have the only critical point zc = 0 then quadratic J may have the only finite attractive cycle! (There is one more critical point at infinity which attracts diverging orbits.) Thus, testing the critical point shows if there is any finite attractive cycle.