1.2: Triangles

- Page ID

- 146231

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

To succeed in this section, you'll need to use some skills from previous courses. While you should already know them, this is the first time they've been required. You can review these skills in CRC's Corequisite Codex. If you have a support class, it might cover some, but not all, of these topics.

The following is a list of learning objectives for this section.

|

.png?revision=1) To access the Hawk A.I. Tutor, you will need to be logged into your campus Gmail account. |

Triangle Basics

The study of Trigonometry inevitably involves understanding everything we possibly can about triangles.

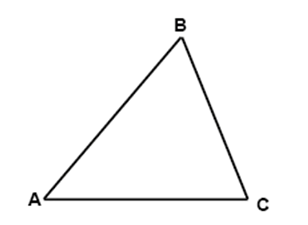

In Figure \( \PageIndex{ 1 } \), the sides are denoted \( \overline{AB} \), \( \overline{BC} \), and \( \overline{AC} \). The vertices (plural of vertex) are \( A \), \( B \), and \( C \). The angles are denoted \( \angle A \), \( \angle B \), and \( \angle C \). Using the notation \( \triangle A B C \), we refer to the triangle by its vertices.

If one tears off the corners of any triangle and lines them up, as shown in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 2 } \), they will always form a straight angle.

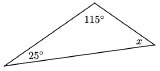

Two of the angles in the triangle shown below are \(25^{\circ}\) and \(115^{\circ}\). Find the third angle.

- Solution

-

To find the third angle, we write an equation.\[\begin{array}{crrclr}

& & x+25+115 & = & 180 & (\text{Triangle Sum}) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\mathrm{Arithmetic} & \implies & x+140 & = & 180 & (\text{add}) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \textrm{Algebra} & \implies & x & = & 40 & (\text{subtract }140\text{ from both sides})\\

\end{array} \nonumber \]The third angle is \(40^{\circ}\).

To get you used to the Mathematical Mantra, every once in a while I will include the "thought processes" during solutions. Just to review, we perform Mathematics in the order we learned it - Arithmetic, Algebra, Trigonometry, \( \ldots \). At each step during a "mechanical" solution process, we should pause and ask ourselves if there is some simple Arithmetic to be done. If not, we move on to any Algebra that can be done. If there is no Algebra to be done, we then move on to Trigonometry.

Thus,

- "\( \mathrm{Arithmetic} \implies\)" in a solution means that there is some Arithmetic we could do to clean up the previous expression

- "\( \xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} \implies\)" means there isn't any Arithmetic but there is some Algebra we could use to clean up the previous expression or equation

- "\( \xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \xcancel{\mathrm{Algebra}} \to \mathrm{Trigonometry} \implies\)" means there isn't any Arithmetic nor is there any Algebra that can be done to clean up the previous step, so we need to start looking at doing something from Trigonometry.

Find all the unknown angles in each figure.

-

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 4 } \)

-

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 5 } \)

- Answer

-

- \(x = 39^{\circ}, 2x = 78^{\circ}, 2x-15 = 63^{\circ}\)

- \(\alpha=40^{\circ}, \beta=140^{\circ}, \gamma=75^{\circ}, \delta=65^{\circ}\)

In any triangle, the longest side is always opposite the largest angle, and the shortest side is opposite the smallest, as illustrated in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 6 } \). Although obvious to most people, this fact will become invaluable as we move through Trigonometry.

It is common (though not necessary) to label the angles of a triangle with capital letters and the side opposite each angle with the corresponding lowercase letter, as shown in the Figure \( \PageIndex{ 7 } \). We will follow this practice unless indicated otherwise.

In \(\triangle F G H, \angle F=48^{\circ}\), and \(\angle G\) is obtuse. Side \(f\) is 6 feet long. What can be concluded about the other sides?

- Solution

-

Because \(\angle G\) is greater than \(90^{\circ}\), we know that \(\angle F+\angle G\) is greater than \(90^{\circ}+48^{\circ}=138^{\circ}\), so \(\angle H\) is less than \(180^{\circ}-138^{\circ}=42^{\circ}\). Thus, \(\angle H<\angle F<\angle G\), and consequently \(h<f<g\). We can conclude that \(h<6\) feet long, and \(g>6\) feet long.

In triangle \(\triangle R S T\), \(\angle S\) is \(72^{\circ}\). The remaining two angles have the same size. Which side is longer, \(s\) or \(t\)?

- Answer

-

\(s\) is longer

The Triangle Inequality

The sum of the lengths of any two sides of a triangle must be greater than the third side; otherwise, the two sides will not meet to form a triangle. This fact is known as the triangle inequality. The theorem is presented without proof (however, you can always find a suitable proof online).

We cannot use the triangle inequality to find the exact lengths of a triangle's sides, but we can find the largest and smallest possible values for the length.

Two sides of a triangle have lengths 7 inches and 10 inches, as shown below. What can be said about the length of the third side?

- Solution

-

We let \(x\) represent the length of the third side of the triangle. By looking at each side in turn, we can apply the triangle inequality in three different ways to get\[7<x+10, \quad 10<x+7, \quad \text { and } \quad x<10+7 \nonumber\]We solve each of these inequalities to find\[-3<x, \quad 3<x, \quad \text { and } \quad x<17 \nonumber\]We already know that \(x>-3\) because \(x\) must be positive, but the other two inequalities do give us new information. The third side must be greater than 3 inches but less than 17 inches long.

Can a triangle be made with three wooden sticks of lengths 14 feet, 26 feet, and 10 feet? Sketch a picture, and explain why or why not.

- Answer

-

No, \(10+14\) is not greater than 26.

Types of Triangles

There are three types of triangles classified by whether they have three equal side lengths, two equal side lengths, or no side lengths that are equal. These are called the equilateral, isosceles, and scalene triangles, respectively.

Equilateral Triangles

Since all three sides of an equilateral triangle have the same length, there is no smallest side for which the smallest angle will be opposite, and there is no largest side for which the largest angle will be opposite. This gives us the following theorem.

All three sides of a triangle are 4 feet long. Find the angles.

- Solution

-

The triangle is equilateral, so all of its angles are equal. Thus\[\begin{array}{crrclr}

& & 3 x & = & 180 & (\text{Triangle Sum}) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & x & = & 60 & (\text{divide both sides by }3) \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]Each of the angles is \(60^{\circ}\).

Find \(x, y\), and \(z\) in the triangle.

- Answer

-

\(x=60^{\circ}, y=8, z=8\)

Isosceles Triangles

In Example \( \PageIndex{ 5 } \), we introduce another common notation used throughout Geometry - the tick mark. We use tick marks on line segments to denote they have equal length. Similarly, tick marks on angles denote that the angles have the same measure.

Explain why \(\alpha=\beta\) in the triangle below.

- Solution

-

Because they are the base angles of an isosceles triangle, \(\theta\) (theta) and \(\phi\) (phi) are equal. Also, \(\alpha=\theta\) because they are vertical angles, and similarly \(\beta=\phi\). Therefore, \(\alpha=\beta\) because they are equal to equal quantities.

Find \(x\) and \(y\) in the triangle.

- Solution

-

The triangle is isosceles, so the base angles are equal. Therefore, \(y=38^{\circ}\). To find the vertex angle, we solve\[ \begin{array}{crrclr}

& & x+38+38 & = & 180 & (\text{Triangle Sum}) \\

\scriptscriptstyle{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} & \implies & x+76 & = & 180 & (\text{add}) \\

\scriptscriptstyle{\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra}} & \implies & x & = & 104 & (\text{subtract }76\text{ from both sides}) \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]The vertex angle is \(104^{\circ}\).

Find \(x\) and \(y\).

- Answer

-

\(x=140^{\circ}, y=9\)

Scalene Triangles

Finally, we have the scalene triangles.

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 14 } \) shows a general scalene triangle. The different "hash marks" on the sides indicate the side lengths are different. The same is true for the angles.

Scalene triangles become important in this course when we learn the Law of Sines and the Law of Cosines.

Classification of Triangles by Largest Angle

Most people are not likely to refer to a triangle by its type (equilateral, isosceles, or scalene); however, knowing the features of each type of triangle is important in Trigonometry. Another classification system for triangles, and one that will be referenced constantly in Trigonometry, is based on the size of the triangle's largest angle. Three classifications exist: right, obtuse, and acute triangles.

Obtuse Triangles

We start with the class of triangles having their largest angle greater than \( 90^{ \circ } \).

Recall that an obtuse angle has measure strictly between \( 90^{ \circ } \) and \( 180^{ \circ } \) (meaning that we exclude \( 90^{ \circ } \) and \( 180^{ \circ } \)). Since the sum of the interior angles of a triangle must be \( 180^{ \circ } \), and one of the angles in an obtuse triangle is greater than \( 90^{ \circ } \), the two smaller angles in an obtuse triangle must sum to strictly less than \( 90^{ \circ } \).

Right Triangles

Reducing the largest possible angle to exactly \( 90^{ \circ } \), we arrive at arguably the most essential triangle classification in Trigonometry - the right triangles.

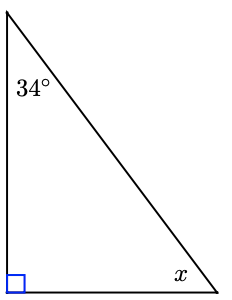

One of the smaller angles of a right triangle is \(34^{\circ}\). What is the third angle?

- Solution

-

The sum of the two smaller angles in a right triangle is \(90^{\circ}\). So\[\begin{array}{crrclr}

& & x+34 & = & 90 & \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & x & = & 56 & (\text{subtract }34\text{ from both sides}) \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]The unknown angle must be \(56^{\circ}\).

Two angles of a triangle are \(35^{\circ}\) and \(45^{\circ}\). Can it be a right triangle?

- Answer

-

No.

Right Triangles: The Pythagorean Theorem

Arguably, the most important theorem in Trigonometry is the Pythagorean Theorem, mainly because without it, Trigonometry would not exist.

The proof of the Pythagorean Theorem is left as a guided exercise in the homework.

A 25-foot ladder is placed against a wall so that its foot is 7 feet from the base of the wall. How far up the wall does the ladder reach?

- Solution

-

We sketch the situation, as shown below, and label any known dimensions. We will call the unknown height \(h\).

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 16 } \)

The ladder forms the hypotenuse of a right triangle, so we can apply the Pythagorean Theorem. Substituting 25 for \(c, 7\) for \(b\), and \(h\) for \(a\), we get the following:\[ \begin{array}{rrrclcl}

& & a^2+b^2 & = & c^2 & & \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & h^2+7^2 & = & 25^2 & \quad & \left( \text{substitution} \right)\\

\scriptscriptstyle\mathrm{Arithmetic} & \implies & h^2+49 & = & 625 & \quad & \left( \text{apply powers} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & h^2 & = & 576 & \quad & \left(\text{subtract }49\text{ from both sides}\right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & h & = & \pm \sqrt{576} & \quad & \left(\text{Extraction of Roots}\right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & h & = & \pm 24 & \quad & \left(\text{simplify the radical}\right) \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]The height must be a positive number, so the solution \(-24\) does not make sense for this problem. The ladder reaches 24 feet up the wall.

A baseball diamond is a square with sides that are 90 feet long. When the catcher sees a runner on first trying to steal second, he throws the ball to the second baseman. Find the straight-line distance from home plate to second base.

- Answer

-

\(90 \sqrt{2} \approx 127.3\) feet

Most people do not realize that the Pythagorean Theorem is a bijection. That is, the converse of the theorem is also true. If the sides of a triangle satisfy the relationship \(a^2+b^2=c^2\), then the triangle must be a right triangle with hypotenuse \( c \). We can use this fact to test whether a given triangle has a right angle.

Mike is paving a patio in his backyard and would like to know if the corner at \(C\) is a right angle. He measures 20 cm along one side from the corner and 48 cm along the other, placing pegs \(P\) and \(Q\) at each position, as shown below. The line joining those two pegs is 52 cm long. Is the corner a right angle?

- Solution

-

If it is a right triangle, its sides must satisfy \(p^2+q^2=c^2\). We find\[\begin{array}{rcl}

p^2+q^2 & = & 20^2+48^2 \\

& = & 400+2304 \\

& = & 2704 \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]and\[\begin{array}{rcl}

c^2 & = & 52^2 \\

& = & 2704 \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]Therefore, yes, because \(p^2+q^2=c^2\), the corner at \(C\) is a right angle.

The sides of a triangle measure 15, 25, and 30 inches long. Is the triangle a right triangle?

- Answer

-

No

The Pythagorean Theorem relates the sides of right triangles. However, for information about the sides of other triangles, the best we can do (without Trigonometry) is the triangle inequality. Moreover, the Pythagorean Theorem doesn't help us find the angles in a triangle - that comes later.

Acute Triangles

Finally, we reduce the largest possible angle within a triangle to strictly less than \( 90^{ \circ } \) and obtain the acute triangles.

Special Triangles

We finally arrive at what could be considered the most essential triangles in elementary Trigonometry - the special triangles. These triangles are revered in Trigonometry because they allow the learner (read as "you") to perform computations without needing a calculator. This, in turn, allows you to focus on concepts rather than computations.

In order to derive one of the theorems we are about to introduce, we need a quick definition.

The altitude of a triangle introduces a right angle, as the following theorem states.

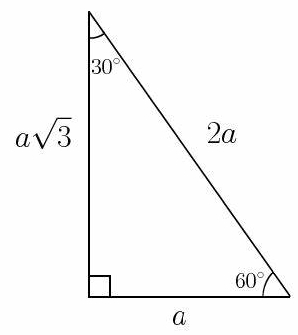

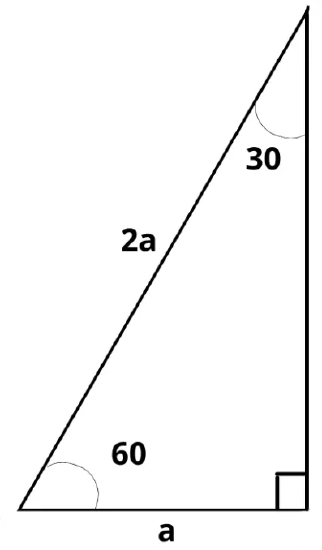

The \( 30^{ \circ } \)-\( 60^{ \circ } \)-\( 90^{ \circ } \) Triangle

Our first of our two special triangles is the \( 30^{ \circ } \)-\( 60^{ \circ } \)-\( 90^{ \circ } \) triangle.

Working with this triangle allows us to know the length of all three sides if only given the length of one side.

Before we go any further, notice in the proof of this theorem the convention of writing \( x = a \sqrt{3} \) instead of \( x = \sqrt{3} a \). This is purposeful. The latter often leads the reader to think that the \( a \) is "under" the square root. It's good form always to write the radical at the end of a term to avoid this visual ambiguity.

Matterhorn Chocolate bars are sold in boxes shaped like triangular prisms. The two triangular ends of a box are equilateral triangles with 8-centimeter sides. When stacking the boxes on a shelf, the second level will be a triangle’s altitude above the bottom level. Find the exact length of the triangle’s altitude, \(h\).

- Solution

-

The altitude divides the triangle into two \(30^{\circ}-60^{\circ}-90^{\circ}\) right triangles, as shown in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 18 } \) below.

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 18 } \)

We see that the hypotenuse is \( 2a = 8 \), which implies the shortest side (opposite the \( 30^{ \circ } \) angle) is \( a=4 \). Hence, the side opposite the \( 60^{ \circ } \) angle is \( a\sqrt{3} = 4 \sqrt{3} \approx 6.9282 \) centimeters long.

A ladder is leaning against a house so that the top is 12 feet above the ground, and the bottom makes a \( 60^{ \circ } \) angle with the ground. Assuming the wall of the house is perpendicular to the ground (and the ground is level), how long is the ladder? State your answer in exact form and round to two decimal places.

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{24}{\sqrt{3}} \approx 13.86 \) feet

Note that the exact form of the answer in Checkpoint \( \PageIndex{ 10 } \) was left as \( \frac{24}{\sqrt{3}} \). While it is true that you could rationalize the denominator to get\[\dfrac{24}{\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{24}{\sqrt{3}} \cdot \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{24 \sqrt{3}}{3} = 8\sqrt{3}, \nonumber \]we will commonly leave radicals in the denominators of purely numeric expressions.

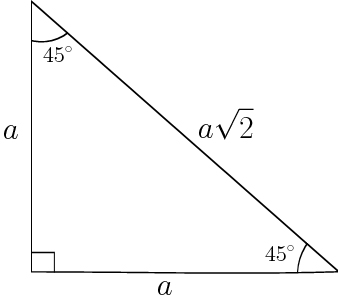

The \( 45^{ \circ } \)-\( 45^{ \circ } \)-\( 90^{ \circ } \) Triangle

The second of our our two special triangles is the \( 45^{ \circ } \)-\( 45^{ \circ } \)-\( 90^{ \circ } \) triangle. This is also known as an isosceles right triangle.

Since the right angle takes \( 90^{ \circ } \), the remaining two angles must share the remaining \( 90^{ \circ } \) evenly. That is, the remaining two angles must be \( 45^{ \circ } \) each.

Just as with our first special triangle, knowing one side of a \( 45^{ \circ } \)-\( 45^{ \circ } \)-\( 90^{ \circ } \) triangle allows us to easily compute the lengths of the remaining sides.

You are hired to build a truss to support a balcony. Figure \( \PageIndex{ 19 } \) shows the design plans you have submitted for the project. What is the length of the beam needed from point \( A \) to point \( D \)?

- Solution

- \( \triangle ABD \) is a \( 45^{ \circ } \)-\( 45^{ \circ } \)-\( 90^{ \circ } \) triangle. Therefore, if the leg length (opposite the \( 45^{ \circ } \) angle) is \( a = 4 \) meters, then beam between points \( A \) and \( D \) must measure \( a\sqrt{2} = 4 \sqrt{2} \approx 5.66 \) meters.

Suppose, instead of knowing the 4-meter lengths in Example \( \PageIndex{ 11 } \), we knew that the length of the beam from \( A \) to \( D \) was 12 meters. How long is the beam from \( B \) to \( D \)?

- Answer

-

\( \dfrac{12}{\sqrt{2}} \approx 8.49 \) meters

Area of a Triangle

Our final review topic for triangles in this section is something necessary at multiple points throughout Trigonometry and Calculus - the area of a triangle.

Compute the area of the triangle in Figure \( \PageIndex{20} \).

- Solution

- We are given the length of one leg of this triangle as 11 inches. Let's call this leg the base. Thus, \( b = 11\). The altitude from the base to its opposite vertex has length 8 inches. Hence, \( h = 8 \). Therefore, the area of this triangle is\[ A = \dfrac{1}{2} b h = \dfrac{1}{2} (11)(8) = 44 \, \text{square inches.} \nonumber \]

Compute the area of the triangle in Figure \( \PageIndex{21} \) if we know that \( c = 5.24 \) and \(h = 1.25\).

- Answer

- 3.28125