2.1: The Trigonometric Functions - Coordinate Definition

- Page ID

- 145916

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)This section is designed assuming you understand the following topics from Arithmetic and Algebra.

- Using inequalities to compare two numbers

- Rationalizing numerators and denominators

- Definition of a function (including argument, value, domain, and range)

- Function notation

- Evaluation of functions

- Find the value of a trigonometric function of an angle given a point on the terminal side of the angle.

- Use the coordinate definition of the trigonometric functions to answer a conceptual question about a trigonometric function.

- Determine the quadrants in which an angle could terminate.

- Evaluate the trigonometric functions at the special angles and the quadrantal angles using the coordinate definition of the trigonometric functions.

- Find the value of a trigonometric function given one of the other trigonometric values.

- Compare the values of trigonometric functions at "non-special" angles without using technology.

- Use the quadrant in which an angle terminates to restrict the sign of a trigonometric function.

Introduction to Coordinate Trigonometry

Armed with our knowledge from the previous chapter, we now define the trigonometric functions. We will be viewing the trigonometric functions from three different perspectives in this course - coordinate trigonometry, right triangle trigonometry, and unit circle trigonometry.1 For the most part, each perspective is mathematically equivalent to the others; however, each has an inherent weakness as a standalone perspective of the trigonometric functions. While you can find a favorite perspective and stick with that one for most of the course, understanding all three is the only way to succeed in Trigonometry.

Let \( \theta \) be an angle in standard position with the point \( P\left( x,y \right) \) on the terminal side of \( \theta \), where \( P \) is not the origin. Define \( r = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} \). The trigonometric functions of the angle \( \theta \) are defined as follows:\[ \begin{array}{|cccc|cccc|}

\hline

\text{Function} & \text{Function} & & & \text{Function} & \text{Function} & & \\

\text{Name} & \text{Notation} & & \text{Definition} & \text{Name} & \text{Notation} & & \text{Definition} \\

\hline

\text{The sine of }\theta & \sin\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & \text{The cosecant of }\theta & \csc\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} \\

\text{The cosine of }\theta & \cos\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & \text{The secant of }\theta & \sec\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} \\

\text{The tangent of }\theta & \tan\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & \text{The cotangent of }\theta & \cot\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} \\

\hline \end{array} \nonumber \]

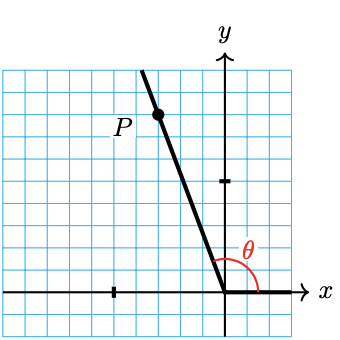

A few notes are in order. First, the trigonometric functions are simply the ratios of \( x \), \( y \), and \( r \), where \( P\left( x,y \right) \) is a point on the terminal side of \( \theta \) and \( r \) is the distance from the origin to the point \( P \) (see Figure \( \PageIndex{ 1 } \) below).

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 1 } \)

Second, because it's the distance from the origin to \(P\), \( r \) is always positive (see the Distance Formula). However, \(x\) and \(y\) can be positive, negative, or zero (but not both zero), depending on the angle \(\theta\). For example, in the second quadrant, \(x\) is negative, but \(y\) is positive, so the cosine and the tangent of angles between \(90^{\circ}\) and \(180^{\circ}\) are negative, but their sines are positive.

Third, referencing Figure \( \PageIndex{ 1 } \), since the tangent function is defined to be \( \frac{y}{x} \) and the terminal side of \( \theta \) is always a ray emanating from the origin,\[ \dfrac{y}{x} = \dfrac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}} = \text{slope of the terminal side of }\theta. \nonumber \]

The interpretation of the value of the tangent function at \( \theta \) being the slope of the ray that is the terminal side of \( \theta \) grants us a potent conceptual understanding of the tangent function. Specifically, since a vertical line has an undefined slope, it makes sense that the tangent function is undefined when \( x = 0 \). Any ray emanating from the origin and going through a point \( P\left( 0,y \right) \), where \( y \neq 0 \), will be vertical. While the secant function is also undefined when \( x = 0 \) (and the cosecant and cotangent functions are undefined when \( y=0 \)), we will hold off on gaining a conceptual understanding of why until we familiarize ourselves with more of the basics of the trigonometric functions.

Unless otherwise stated, all angles from this point forward will be considered angles in standard position.

Find the values of the six trigonometric functions if \( P\left( -3, -8 \right) \) is on the terminal side of \( \theta \).

- Solution

- It's a good habit in Trigonometry to start by sketching a graph of the situation.

We have \( x = -3 \), \( y = -8 \), and \( r = \sqrt{(-3)^2 + (-8)^2} = \sqrt{9 + 64} = \sqrt{73} \). Therefore,\[ \begin{array}{rccclcrcccl}

\sin\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & = & \dfrac{-8}{\sqrt{73}} = -\dfrac{8}{\sqrt{73}} & \qquad & \csc\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} & = & \dfrac{\sqrt{73}}{-8} = -\dfrac{\sqrt{73}}{8} \\

\cos\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & = & \dfrac{-3}{\sqrt{73}} = -\dfrac{3}{\sqrt{73}} & \qquad & \sec\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} & = & \dfrac{\sqrt{73}}{-3} = -\dfrac{\sqrt{73}}{3} \\

\tan\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & = & \dfrac{-8}{-3} = \dfrac{8}{3} & \qquad & \cot\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} & = & \dfrac{-3}{-8} = \dfrac{3}{8} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

In Algebra, we learned to rationalize denominators so we could "simplify" expressions like \( -\frac{8}{\sqrt{73}} \); however, in Trigonometry, such manipulations often are pointless. The rule of thumb I will adhere to in this textbook is to rationalize denominators if the denominator involves a variable (e.g., \( \frac{3}{\sqrt{x} - 2} \)). In all other cases (specifically, when the numerator and denominator do not contain variables), I will only rationalize denominators if there is an "obvious" benefit.

In the case of \( -\frac{8}{\sqrt{73}} \), if we tried to rationalize the denominator, we would get\[ -\dfrac{8}{\sqrt{73}} \cdot \dfrac{\sqrt{73}}{\sqrt{73}} = - \dfrac{8 \sqrt{73}}{73}, \nonumber \]which is no better than the original fraction.

- Find the equation of the terminal side of the angle in the previous example. (Hint: The terminal side lies on a line that goes through the origin and the point \( \left( -3,-8 \right) \)).

- Show that the point \( P^{\prime}\left( -6,-16 \right) \) also lies on the terminal side of the angle.

- Compute the trigonometric ratios for \( \theta \) using the point \( P^{\prime} \) instead of \( P \).

- Answers

-

- \(y=\dfrac{8}{3} x\)

- \((-6,-16)\) satisfies \(y=\frac{8}{3} x\). That is, the equation \(-16=\frac{8}{3}(-6)\) is true.

- \(r^2=(-6)^2+(-16)^2=292\), so \(r=\sqrt{292}=2\sqrt{73}\). Then\[ \begin{array}{rccclcrcccl}

\sin\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & = & \dfrac{-16}{2\sqrt{73}} = -\dfrac{8}{\sqrt{73}} & \qquad & \csc\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} & = & \dfrac{2\sqrt{73}}{-16} = -\dfrac{\sqrt{73}}{8} \\

\cos\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & = & \dfrac{-6}{2\sqrt{73}} = -\dfrac{3}{\sqrt{73}} & \qquad & \sec\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} & = & \dfrac{2\sqrt{73}}{-6} = -\dfrac{\sqrt{73}}{3} \\

\tan\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & = & \dfrac{-16}{-6} = \dfrac{8}{3} & \qquad & \cot\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} & = & \dfrac{-6}{-16} = \dfrac{3}{8} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

Find the values of \(\cos \left(\theta\right)\) and \(\tan \left(\theta\right)\) if \(\theta\) is an obtuse angle with \(\sin \left(\theta\right)=\frac{1}{3}\).

- Solution

-

Because \(\theta\) is obtuse, the terminal side of the angle lies in the second quadrant, as shown in the figure below.

Because \(\sin \left(\theta\right)=\frac{1}{3}\), we know that \(\frac{y}{r}=\frac{1}{3}\), so we can choose a point \(P\) with \(y=1\) and \(r=3\). To find \(\cos \left(\theta\right)\) and \(\tan \left(\theta\right)\), we need to know the value of \(x\). From the Pythagorean Theorem,\[\begin{array}{rrrclcl}

& & x^2+1^2 & = & 3^2 & \quad & \left( \text{substitute known values} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\mathrm{Arithmetic} & \implies & x^2 + 1 & = & 9 & \quad & \left( \text{Laws of Exponents} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & x^2 & = & 8 & \quad & \left( \text{subtract }1\text{ from both sides} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & x & = & \pm \sqrt{8} & \quad & \left( \text{Extraction of Roots} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & x & = & \pm 2 \sqrt{2} & \quad & \left( \text{simplifying radicals} \right) \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]Remembering that \(x\) is negative in the second quadrant, we get that \( x = -2\sqrt{2} \). Thus,\[\cos \left(\theta\right)=\dfrac{x}{r}=\dfrac{-2\sqrt{2}}{3} \quad \text { and } \quad \tan \left(\theta\right)=\dfrac{y}{x}=\dfrac{-1}{2\sqrt{2}}\nonumber \]

Example \( \PageIndex{ 2 } \) illustrates a common theme in Trigonometry - we will often use the quadrant of the terminal side of an angle to inform our decision on the sign of \( x \)- and \( y \)-values.

If given a negative trigonometric ratio, as in Checkpoint \( \PageIndex{ 2 } \), it is important to remember that the value of \( r \) is always non-negative.2

- Sketch an obtuse angle \(\theta\) whose cosine is \(\frac{-8}{17}\).

- Find the cosecant and the tangent of \(\theta\).

- Answers

-

- \(\csc \left(\theta\right) = \dfrac{17}{15}, \tan \left(\theta\right) = \dfrac{-15}{8}\)

Function Notation

We use the notation \(y = f(x)\) to indicate that \(y\) is a function of \(x\), that is, \(x\) is the input variable (also known as the independent variable) and \(y\) is the output variable (also known as the dependent variable).

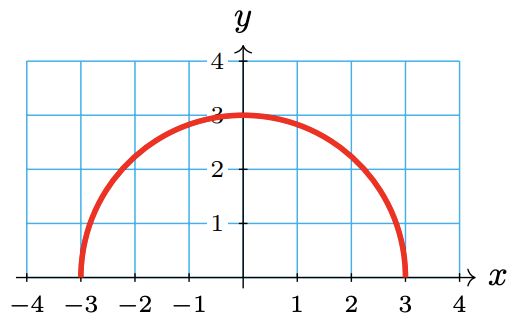

Graph the function \(y = f(x) = \sqrt{9 − x^2}\).

- Solution

-

There are two ways to graph this function - a bad way, and a good way.

Bad Way

The only reason I call this the "bad way" is because, if you need to use this method to graph the function, then you need to review your old algebra. This method involves point plotting, which is the absolute worst way to obtain the graph of a function. Still, I will howcase the idea here.

We choose several values for the input variable, \(x\), and evaluate the function to find the corresponding values of the output variable, \(y\). For example,\[f(-3) = \sqrt{9 - (-3)^2} = 0\nonumber \]We plot the points in the table and connect them to obtain the graph shown below.

\(x\) -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 \(y\) 0 \(\sqrt{5}\) \(2\sqrt{2}\) 3 \(2\sqrt{2}\) \(\sqrt{5}\) 0 Good Way

In Section 1.4, we reviewed the equation of a circle. At that time, we recalled that the equation of a circle centered at the origin having radius \( r \) is\[ x^2 + y^2 = r^2. \nonumber \]If we solve this equation for \( y \), we get\[ y = \pm \sqrt{r^2 - x^2}. \nonumber \]If we restrict the \( y \)-values to not be negative, then this equation becomes\[ y = \sqrt{r^2 - x^2}, \nonumber \]which represents the top half of a circle of radius \( r \). Comparing this equation to the function \( f(x) = \sqrt{9 − x^2} \), we can see this function represents the top half of a circle of radius 3.

Of course, we don’t always use \(x\) and \(y\) for the input and output variables. In Example \( \PageIndex{ 3 } \), we could write \(w = f(t) = \sqrt{9 − t^2}\) for the function, so that \(t\) is the independent variable and \(w\) is the dependent variable. The table of values and the graph are the same; only the names of the variables have changed.

When we discuss trigonometric functions, there are several variables involved. Our definitions of the trigonometric functions involve four variables: \(x, y, r\), and \(\theta\), as illustrated below.

If the value of \(r\) is fixed for a given situation, then \(x\) and \(y\) are both functions of \(\theta\). This means that the values of \(x\) and \(y\) depend only on the value of the angle \(\theta\). If \(r = 1\), we have\[\begin{array}{rcccl}

x & = & f(\theta) & = & \cos \left(\theta\right) \\

y & = & g(\theta) & = & \sin \left(\theta\right) \\

\end{array}\nonumber \]When you have a situation where the coordinates, \( x \) and \( y \), can be written in terms of another common variable (in this case, \( \theta \)), we say that \( x \) and \( y \) are parametrized by the independent variable \( \theta \).

This topic will become very important later in this course.

We will sometimes write \(\cos \theta\) when we really mean \(\cos\left(\theta\right)\). This is a common, but accepted, abuse of notation reserved specifically for the trigonometric functions (and, at times, the logarithmic functions).

A common mistake is to think of \(\cos \theta\) or \(\cos(\theta)\) as a product, cos times \(\theta\), but this makes no sense, because ”cos” by itself has no meaning. Remember that \(\cos \theta\) represents a single number, namely the output of the cosine function.

Trigonometric Values at Special Angles

In Section 1.2, we introduced the special triangles. These triangles play a crucial role in Trigonometry. In fact, the angles \(30^{\circ}, 45^{\circ}\) and \(60^{ \circ }\) are called the special angles because we can express the exact values of their trigonometric functions in terms of radicals. In the following example, we explore the values of the trigonometric functions at one of the special angles.

Find the values of all six trigonometric functions of \( 30^{ \circ } \).

- Solution

- Like any good Trigonometry student, we start with a sketch.

Unfortunately, we were not given a value for a point on the terminal side of \( \theta = 30^{ \circ } \); however, recall the following figure from the Special Triangles subsection of Section 1.2.

Rotating this special triangle counterclockwise by \( 90^{ \circ } \), we can visualize fitting it to our first sketch, almost like a jigsaw puzzle.

If we let \( a = 1 \) (a completely arbitrary choice), we get\[ x = \sqrt{3}, \quad y = 1, \text{ and} \quad r = 2. \nonumber \]Therefore,\[ \begin{array}{rccclcrcccl}

\sin\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & = & \dfrac{1}{2} & \qquad & \csc\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} & = & 2 \\

\cos\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & = & \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} & \qquad & \sec\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} & = &\dfrac{2}{\sqrt{3}} \\

\tan\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & = & \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}} & \qquad & \cot\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} & = & \sqrt{3} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

At this point, you should be asking yourself why we arbitrarily chose \( a = 1 \) in Example \( \PageIndex{ 4 } \) to "lock in" the value of the point \( P\left( \sqrt{3},1 \right) \). Had we chosen, for example, \( a = 5 \), we would have gotten\[ x = 5\sqrt{3}, \quad y = 5, \text{ and} \quad r = 10. \nonumber \]Therefore,\[ \begin{array}{rccclcrcccl}

\sin\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & = & \dfrac{5}{10} = \dfrac{1}{2} & \qquad & \csc\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} & = & \dfrac{10}{5} = 2 \\

\cos\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & = & \dfrac{5\sqrt{3}}{10} = \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} & \qquad & \sec\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} & = & \dfrac{10}{5\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{2}{\sqrt{3}} \\

\tan\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & = & \dfrac{5}{5\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}} & \qquad & \cot\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} & = & \dfrac{5\sqrt{3}}{5} = \sqrt{3} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]Notice that the values of the trigonometric functions didn't change? In fact, if we had chosen to leave \( a \) "as is," we would have arrived at\[ x = a\sqrt{3}, \quad y = a, \text{ and} \quad r = 2a. \nonumber \]Therefore,\[ \begin{array}{rccclcrcccl}

\sin\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & = & \dfrac{a}{2a} = \dfrac{1}{2} & \qquad & \csc\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} & = & \dfrac{2a}{a} = 2 \\

\cos\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & = & \dfrac{a\sqrt{3}}{2a} = \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} & \qquad & \sec\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} & = & \dfrac{2a}{a\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{2}{\sqrt{3}} \\

\tan\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & = & \dfrac{a}{a\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}} & \qquad & \cot\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} & = & \dfrac{a\sqrt{3}}{a} = \sqrt{3} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]The choice of \( a \) doesn't change the values of the trigonometric functions at all! This demonstration implies (but does not prove) that the values of the trigonometric functions do not depend on which point you choose on the terminal side of \( 30^{ \circ } \) - just as long as that point is not the origin.

The result of this last statement is beneficial. If we have angles from our special triangles, we can just set \( a = 1 \) in those special triangles to get the \( x \)- and \( y \)-values of the related point.

Find the values of the six trigonometric functions at \( \theta = 45^{ \circ } \).

- Answer

-

\[ \begin{array}{rclcrcl}

\sin\left( 45^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \qquad & \csc\left( 45^{ \circ } \right) & = & \sqrt{2} \\

\cos\left( 45^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \qquad & \sec\left( 45^{ \circ } \right) & = & \sqrt{2} \\

\tan\left( 45^{ \circ } \right) & = & 1 & \qquad & \cot\left( 45^{ \circ } \right) & = & 1 \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

We do not need to limit our use of the special angles and special triangles to angles given in the first quadrant. The following example illustrates our tactics if given an angle terminating in a quadrant other than the first, where we can use our knowledge of the special triangles.

Find exact values for all six trigonometric functions of \(240^{\circ}\).

- Solution

-

An angle of \(240^{\circ}\) lies in the third quadrant, as seen in the figure below.

If we want to work with a smaller angle, we consider the angle between the terminal side of \( 240^{ \circ } \) and the negative \( x \)-axis. This can be found by taking the larger angle (\( 240^{ \circ } \)) and subtracting off the smaller angle (the \( 180^{ \circ } \) angle that gets to the negative \( x \)-axis).\[ 240^{ \circ } - 180^{ \circ } = 60^{ \circ } \nonumber \]This action is illustrated in the figure below.

That \( 60^{ \circ } \) angle between \( 240^{ \circ } \) and \( 180^{ \circ } \) should be familiar.

Superimposing this \( 30^{ \circ } \)-\( 60^{ \circ } \)-\( 90^{ \circ } \) special triangle into our graph, we get the following figure.

Using our new knowledge that we can let \( a \) be any convenient number, we choose \( a = 1 \). However, here is where we need to be careful! If \( a = 1 \), it is not true that \( x = a = 1 \). This is because the point \( P\left( x,y \right) \) on the terminal side of \( 240^{ \circ } \) must be in \( \mathrm{QIII} \). Therefore, \( x = -1 \). Likewise, \( y = -\sqrt{3} \). No matter what, however, \( r > 0 \). Thus, \( r = 2a = 2 \). We now compute the values of the trigonometric functions.\[ \begin{array}{rccclcrcccl}

\sin\left( 240^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & = & -\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} & \qquad & \csc\left( 240^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} & = & -\dfrac{2}{\sqrt{3}} \\

\cos\left( 240^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & = & -\dfrac{1}{2} & \qquad & \sec\left( 240^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} & = & -2 \\

\tan\left( 240^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & = & \sqrt{3} & \qquad & \cot\left( 240^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} & = & \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

Find exact values for the sine, cosine, and tangent of \(300^{\circ}\).

- Answer

-

\(\sin \left(300^{\circ}\right)=\dfrac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}, \quad \cos \left(300^{\circ}\right)=\dfrac{1}{2}, \quad \tan \left(300^{\circ}\right)=-\sqrt{3}\)

All angles between \( 0^{ \circ } \) and \( 360^{ \circ } \) associated with the special angles are shown in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 2 } \) below. It would be best if you memorized these values or be able to calculate them quickly.

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 2 } \)

Trigonometric Values at Quadrantal Angles

In Section 1.4, we introduced the quadrantal angles. Evaluating trigonometric functions at quadrantal angles is much easier than at nonquadrantal angles. However, we have to watch out for division by zero.

Find the values of the six trigonometric functions at \( -270^{ \circ } \).

- Solution

- We get the following figure by creating a quick sketch for this situation and remembering that negative angles open clockwise.

We took the liberty to label a point on the terminal side of \( -270^{ \circ } \). In this case, \( x = 0 \), \( y = 1 \), and \( r = 1 \). Therefore,\[ \begin{array}{rccclcrcccl}

\sin\left( -270^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & = & \dfrac{1}{1} = 1 & \qquad & \csc\left( -270^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} & = & \dfrac{1}{1} = 1 \\

\cos\left( -270^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & = & \dfrac{0}{1} = 0 & \qquad & \sec\left( -270^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} & = &\dfrac{1}{0} = \text{ UNDEFINED} \\

\tan\left( -270^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & = & \dfrac{1}{0} = \text{ UNDEFINED} & \qquad & \cot\left( -270^{ \circ } \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} & = & \dfrac{0}{1} = 0 \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

Example \( \PageIndex{ 6 } \) illustrates the fact that there are angles for which some of the trigonometric functions are not defined. In terms of functions, we would say that these functions have domain restrictions. We will discuss this in more detail later in this textbook. It suffices to know that the tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant functions each have angles for which the functions are undefined. You can see from the definitions of these trigonometric functions where these domain issues occur (either when \( x = 0 \) or when \( y = 0 \), depending on the trigonometric function).

Find the values of the six trigonometric functions at \( 540^{ \circ } \).

- Answer

-

\[ \begin{array}{rclcrcl}

\sin\left( 540^{ \circ } \right) & = & 0 & \qquad & \csc\left( 540^{ \circ } \right) & = & \text{ UNDEFINED} \\

\cos\left( 540^{ \circ } \right) & = & -1 & \qquad & \sec\left( 540^{ \circ } \right) & = & -1 \\

\tan\left( 540^{ \circ } \right) & = & 0 & \qquad & \cot\left( 540^{ \circ } \right) & = & \text{ UNDEFINED} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

Very technically, we prefer not write, "\( \cot\left( 540^{ \circ } \right) = \text{ UNDEFINED}\)." It sounds odd. Read the following sentence out loud, and you will understand what we mean, "This value equals undefined."

Instead, you could write, "\( \cot\left( 540^{ \circ } \right) \) is undefined."

Comparing Values of the Trigonometric Functions

Understanding how to compare the values of a trigonometric function for different angles can be beneficial in future math courses. For example, in Calculus, you will need to have an innate understanding that \( \sin \left(50^{ \circ }\right) < \sin\left( 80^{ \circ } \right) \). The following example illustrates the thought process.

Without reaching for technology, can you determine which is greater, \( \sin\left( 50^{ \circ } \right) \) or \( \sin\left( 80^{ \circ } \right) \)?

- Solution

- Quickly sketching two angles, \( \alpha = 50^{ \circ } \) and \( \beta = 80^{ \circ } \), we get the following graph.

By itself, this graph is not helpful; however, if we recall that the sine of an angle is defined to be \( \frac{y}{r} \), where \( \left( x,y \right) \) is any point on the terminal side of the angle and \( r \) is the distance from the origin to the point, then we could choose points on the terminal sides of \( \alpha = 50^{ \circ }\) and \( \beta = 80^{ \circ } \) such that \( r = 1 \). This gives us \( \sin\left( 50^{ \circ } \right) = \frac{y_1}{r} = \frac{y_1}{1} = y_1 \) and \( \sin\left( 80^{ \circ } \right) = \frac{y_2}{r} = \frac{y_2}{1} = y_2 \) (see the figure below).

From this figure, we can see that \( y_1 < y_2\). Therefore, \( \sin\left( 50^{ \circ } \right) < \sin\left( 80^{ \circ } \right)\).

Without reaching for technology, can you determine which is greater, \( \cos\left( 100^{ \circ } \right) \) or \( \cos\left( 170^{ \circ } \right) \)?

- Answer

-

\( \cos\left( 100^{ \circ } \right) \) is greater than \( \cos\left( 170^{ \circ } \right) \)

Quadrants and the Signs of the Trigonometric Functions

Give the sign of the sine, cosine, and tangent of the angle.

- \(200^{\circ}\)

- \(300^{\circ}\)

- Solutions

-

- In standard position, the terminal side of an angle of \(200^{\circ}\) lies in \( \mathrm{QIII} \) (see figure (a) below). In the third quadrant, \(x < 0\) and \(y < 0\), but \(r > 0\). Thus, \(\sin \left( 200^{\circ}\right) \) is negative, \(\cos \left(200^{\circ}\right)\) is negative, and \(\tan \left(200^{\circ}\right)\) is positive.

- \(300^{\circ} \in \mathrm{QIV}\), so \(x > 0\) and \(y < 0\), and \(r > 0\). Thus, \(\sin \left(300^{\circ}\right)\) is negative, \(\cos \left(300^{\circ}\right)\) is positive, and \(\tan \left(300^{\circ}\right)\) is negative.

- In standard position, the terminal side of an angle of \(200^{\circ}\) lies in \( \mathrm{QIII} \) (see figure (a) below). In the third quadrant, \(x < 0\) and \(y < 0\), but \(r > 0\). Thus, \(\sin \left( 200^{\circ}\right) \) is negative, \(\cos \left(200^{\circ}\right)\) is negative, and \(\tan \left(200^{\circ}\right)\) is positive.

Example \( \PageIndex{ 8 } \) demonstrates a common need in Trigonometry - to determine the sign of a trigonometric function. Luckily, our task is fairly easy.

Since the value of \( r \) is always positive (unless the point is the origin), the signs of the trigonometric functions are completely dependent on the signs of the \( x \)- and \( y \)-coordinates of the point on the terminal side of \( \theta \).\[ \begin{array}{|c|c|c|}

\hline \text{The sign of...} & \text{... which is...} & \text{...depends on the value(s) of...} \\

\hline \sin\left( \theta \right) & \dfrac{y}{r} & y \\

\hline \cos\left( \theta \right) & \dfrac{x}{r} & x \\

\hline \tan\left( \theta \right) & \dfrac{y}{x} & x \text{ and } y \\

\hline \csc\left( \theta \right) & \dfrac{r}{y} & y \\

\hline \sec\left( \theta \right) & \dfrac{r}{x} & x \\

\hline \cot\left( \theta \right) & \dfrac{x}{y} & x \text{ and } y \\

\hline \end{array} \nonumber \]Therefore, the signs of the sine and cosecant functions completely depend on the signs of the \( y \)-value of the point on the terminal side of \( \theta \). This is why the sine and cosecant are positive in \( \mathrm{QI} \) and \( \mathrm{QII} \). On the other hand, these functions are negative when the angle terminates in either \( \mathrm{QIII} \) or \( \mathrm{QIV} \).

Likewise, the signs of the cosine and secant functions completely depend on the signs of the \( x \)-value of the point on the terminal side of \( \theta \). Hence, the cosine and secant functions are positive in \( \mathrm{QI} \) and \( \mathrm{QIV} \) - they are negative in \( \mathrm{QII} \) and \( \mathrm{QIII} \).

Finally, since the tangent and cotangent functions rely on the values of both \( x \) and \( y \), we must consider what would make these ratios positive and negative. If the values of \( x \) and \( y \) are both positive or both negative, their ratios will be positive. This occurs in the first and third quadrants. Therefore, the tangent and cotangent functions are positive in \( \mathrm{QI} \) and \( \mathrm{QIII} \) - they are negative in \( \mathrm{QII} \) and \( \mathrm{QIV} \).

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 3 } \) summarizes these results.

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 3 } \)

The signs of the trigonometric functions depend on the trigonometric function in question and the quadrant where the terminal side of \( \theta \) lies.

All trigonometric functions are positive when the terminal side of \( \theta \) is in the first quadrant.

Sine and the cosecant functions are positive when the terminal side of \( \theta \) is in the second quadrant.

Tangent and the cotangent functions are positive when the terminal side of \( \theta \) is in the third quadrant.

Cosine and the secant functions are positive when the terminal side of \( \theta \) is in the fourth quadrant.

The bold lettering in the previous theorem is purposeful. Figure \( \PageIndex{ 4 } \) gives the lovely mnemonic, "All Student Take Calculus," to remember that all trigonometric functions are positive in the first quadrant, the sine and cosecant functions are positive in the second quadrant, the tangent and cotangent functions are positive in the third quadrant, and the cosine and secant functions are positive in the fourth quadrant.

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 4 } \)

Given that \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = -\frac{3}{5} \) and \( \theta \) terminates in \( \mathrm{QII} \), find the values of the remaining trigonometric functions of \( \theta \).

- Solution

- Since we are given \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = -\frac{3}{5} \), we know the ratio of \( x \) to \( r \) is \( -\frac{3}{5} \). Letting \( x = -3 \) and \( r = 5 \), we find \( y \) by solving\[ \begin{array}{rrrclcl}

& & r & = & \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} & \quad & \left( \text{definition of }r \right)\\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & 5 & = & \sqrt{(-3)^2 + y^2} & \quad & \left( \text{substitute values} \right)\\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & 25 & = & 9 + y^2 & \quad & \left( \text{Laws of Exponents and squaring both sides} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & 16 & = & y^2 & \quad & \left( \text{subtracting }9\text{ from both sides} \right)\\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & \pm 4 & = & y & \quad & \left( \text{Extraction of Roots} \right) \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]Using the fact that \( \theta \in \mathrm{QIII} \), we throw out the positive possibility and set \( y = -4 \). We now have everything we need!\[ \begin{array}{rclcrcl}

\sin\left( \theta \right) & = & - \dfrac{4}{5} & \qquad & \csc\left( \theta \right) & = & -\dfrac{5}{4} \\

\cos\left( \theta \right) & = & - \dfrac{3}{5} & \qquad & \sec\left( \theta \right) & = & -\dfrac{5}{3} \\

\tan\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{3}{4} & \qquad & \cot\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{4}{3} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

In which quadrant(s) is the sine negative but the cosine positive?

- Answer

-

\( \mathrm{QIV} \)

Proving that Values of the Trigonometric Functions are Independent of \( P \)

Let \( P\left( x,y \right) \) and \( \bar{P}\left( \bar{x}, \bar{y} \right) \) be two distinct points on the terminal side of \( \theta \), neither of which are the origin, and let \( r = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} \) and \( \bar{r} = \sqrt{\bar{x}^2 + \bar{y}^2} \). Figure \( \PageIndex{ 5 } \) illustrates the scenario.

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 5 } \)

Since \( \triangle AOP \) and \( \triangle \bar{A}O\bar{P} \) are similar,\[ \begin{array}{rcccccrccccl}

\sin\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & = & \dfrac{\bar{y}}{\bar{r}} & \qquad & \csc\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} & = & \dfrac{\bar{r}}{\bar{y}} \\

\cos\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & = & \dfrac{\bar{x}}{\bar{r}} & \qquad & \sec\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} & = & \dfrac{\bar{r}}{\bar{x}} \\

\tan\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & = & \dfrac{\bar{y}}{\bar{x}} & \qquad & \cot\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} & = & \dfrac{\bar{x}}{\bar{y}} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]This proves the following theorem.

Let \( P\left( x,y \right) \) and \( \bar{P}\left( \bar{x}, \bar{y} \right) \) be two distinct points on the terminal side of \( \theta \), neither of which are the origin, and let \( r = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} \) and \( \bar{r} = \sqrt{\bar{x}^2 + \bar{y}^2} \). Then\[ \begin{array}{rccclcrcccl}

\sin\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{r} & = & \dfrac{\bar{y}}{\bar{r}} & \qquad & \csc\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{y} & = & \dfrac{\bar{r}}{\bar{y}} \\

\cos\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{r} & = & \dfrac{\bar{x}}{\bar{r}} & \qquad & \sec\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{r}{x} & = &\dfrac{\bar{r}}{\bar{x}} \\

\tan\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{y}{x} & = & \dfrac{\bar{y}}{\bar{x}} & \qquad & \cot\left( \theta \right) & = & \dfrac{x}{y} & = & \dfrac{\bar{x}}{\bar{y}} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

Footnotes

1 Since we are not covering right triangle trigonometry and unit circle trigonometry in this chapter, I chose to only bold coordinate trigonometry.

2 For those of you who have seen advanced topics in Trigonometry before, you know that the claim, "\( r \) is always non-negative" is a bit of an exaggeration. When we introduce the polar coordinate system near the end of this course, we allow \( r \) to be negative.

Skills Refresher

Review the following skills you will need for this section.

For Problems 1 - 4, evaluate the function.

-

\(f(x)=x^2-2 x\)

-

\(f(-3)\)

-

\(f(a-3)\)

-

\(f(a)-5\)

-

\(f(a)-f(5)\)

-

-

\(g(x)=\sqrt{x+4}\)

-

\(g(9)\)

-

\(g(4h)\)

-

\(g(0) + g(1)\)

-

\(g(c^2)\)

-

-

\(F(x) = \dfrac{2}{x}\)

-

\(F\left(\dfrac{-1}{2}\right)\)

-

\(F\left(\dfrac{w}{2}\right)\)

-

\(F(w + 2)\)

-

\(F(w) + F(2)\)

-

-

\(G(x) = 2^x\)

-

\(G(-3)\)

-

\(G(a+3)\)

-

\(G(a) + G(3)\)

-

\(G\left(\dfrac{3}{2}\right)\)

-

For Problems 5 - 12, rationalize the denominator.

-

\(\dfrac{7}{\sqrt{5}}\)

-

\(\sqrt{\dfrac{2}{7}}\)

-

\( \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{32}} \)

-

\( \dfrac{3}{2\sqrt{5x}} \)

-

\( \dfrac{11}{6 - \sqrt{3}} \)

-

\( \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{3 - \sqrt{5}} \)

-

\( \dfrac{\sqrt{5} - 2}{\sqrt{3} - \sqrt{5}} \)

-

\( \dfrac{-4}{\sqrt[4]{3x^3}} \)

For Problems 13 and 14, rationalize the numerator.

-

\( \dfrac{11 - \sqrt{2}}{6} \)

-

\( \dfrac{\sqrt{x} - \sqrt{h}}{\sqrt{x}} \)

- Answers

-

-

-

15

-

\(a^2 - 8a + 15\)

-

\(a^2 - 2a - 5\)

-

\(a^2 - 2a - 15\)

-

-

-

\(\sqrt{13}\)

-

\(2 \sqrt{h+1}\)

-

\(2 + \sqrt{5}\)

-

\(\sqrt{c^2 + 4}\)

-

-

-

-4

-

\(\dfrac{4}{w}\)

-

\(\dfrac{2}{w+2}\)

-

\(\dfrac{2}{w} + 1\)

-

-

-

\(\dfrac{1}{8}\)

-

\(8(2^a)\)

-

\(2^a + 8\)

-

\(2 \sqrt{2}\)

-

-

\( \dfrac{7\sqrt{5}}{5} \)

-

\( \dfrac{\sqrt{14}}{7} \)

-

\( \dfrac{\sqrt{6}}{8} \)

-

\( \dfrac{3\sqrt{5x}}{10x} \)

-

\( \dfrac{6 + \sqrt{3}}{3} \)

-

\( \dfrac{3\sqrt{3} + \sqrt{15}}{4} \)

-

\( \dfrac{-\sqrt{15} + 2\sqrt{3} - 5 + 2 \sqrt{5}}{2} \)

-

\( \dfrac{-4\sqrt[4]{27x^9}}{3x^3} \)

-

\( \dfrac{3}{22+2\sqrt{2}} \)

-

\( \dfrac{x - h}{x + \sqrt{hx}} \)

-

Homework

Vocabulary Check

-

___ defines new functions in terms of the coordinates of points on the Cartesian Plane and their distance to the origin.

-

In the function notation \( f(x) \), \( x \) is called the ___ variable.

-

\( 30^{ \circ } \), \( 45^{ \circ } \), and \( 60^{ \circ } \) are examples of ___ angles.

-

A helpful way to remember in which quadrants the trigonometric functions are positive is ASTC. This stands for A___ S___ T___ C___.

Concept Check

-

We define the trigonometric ratios of any angle by placing the angle in standard position and choosing a point on the terminal side, with \(r = \sqrt{x^2+y^2}\).

-

We use the notation \(y = f(x)\) to indicate that \(y\) is a function of \(x\), that is, \(x\) is the input variable and \(y\) is the output variable.

-

The trigonometric ratios \(\sin \theta\) and \(\cos \theta\) are functions of the angle \(\theta\).

-

If \(\theta\) is an angle in standard position, and \((x,y)\) is a point on its terminal side, with \(r = \sqrt{x^2+y^2}\), then \(\sin \left(\theta\right) = \frac{y}{r} \quad \cos \left(\theta\right) = \frac{x}{r} \quad \tan \left(\theta\right) = \frac{y}{x} \quad \csc \left(\theta\right) = \frac{r}{y} \quad \sec \left(\theta\right) = \frac{r}{x} \quad \cot \left(\theta\right) = \frac{x}{y} \)

-

There are always two angles between \(0^{\circ}\) and \(360^{\circ}\) (except for the quadrantal angles) with a given trigonometric ratio.

True or False? For Problems 10 - 17, determine if the statement is true or false. If true, cite the definition or theorem stated in the text supporting your claim. If false, explain why it is false and, if possible, correct the statement.

-

The angle used in the coordinate definition of the trigonometric functions is measured from the positive \( y \)-axis.

-

The value, \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \), is "more correct" than its rationalized form \( \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \).

-

\( \cos \theta \) is another notation for \( \cos\left( \theta \right) \).

-

\( 3\sin\left( 30^{ \circ } \right) = \sin\left( 3 \cdot 30^{ \circ } \right) = \sin\left( 90^{ \circ } \right) = 1\).

-

\( \sin\left( \theta \right) \) can be undefined.

-

\( \tan\left( \theta \right) \) can be undefined.

-

All students take Calculus.

-

If \( P \) and \( Q \) are points on the terminal side of \( \theta \), where neither are the origin, and \( Q \) is three times the distance from the origin as \( P \), the values of the trigonometric functions defined by \( Q \) are three times the values of the same trigonometric functions defined by \( P \).

Basic Skills

For Problems 18 - 27, find the exact values of all six trigonometric functions of \( \theta \) if the given point is on the terminal side of \( \theta \).

-

\( \left( 3,4 \right) \)

-

\( \left( -\sqrt{3},1 \right) \)

-

\( \left( -5, -5 \right) \)

-

\( \left( 15,-8 \right) \)

-

\( \left( 2,3 \right) \)

-

\( \left( -\sqrt{5}, 1 \right) \)

-

\( \left( -6,0 \right) \)

-

\( \left( 0,-2 \right) \)

-

\( \left( A,B \right) \)

-

\( \left( -6t,9t \right) \) (assume \( t > 0 \))

In Problems 28 and 29, use technology to find the approximate values of all six trigonometric functions of \( \theta \) if the given point is on the terminal side of \( \theta \).

-

\( \left( 1.27, 5.03 \right) \)

-

\( \left( 3.39, -7.46 \right) \)

For Problems 30 - 33,

(a) Give the coordinates of point \(P\) on the terminal side of the angle.

(b) Find the distance from the origin to point \(P\).

(c) Find \(\cos \theta, \sin \theta\), and \(\tan \theta\).

For Problems 34 - 37, determine the \( \sin\left( \theta \right) \), \( \cos\left( \theta \right) \), and \( \tan\left( \theta \right) \) for the \( \theta \) in the given graph. Assume \( \theta \) is in standard position.

-

-

-

-

-

Complete the table with exact values.

\(\theta\) \(30^{\circ}\) \(45^{\circ}\) \(60^{\circ}\) \(120^{\circ}\) \(135^{\circ}\) \(150^{\circ}\) \(210^{\circ}\) \(225^{\circ}\) \(240^{\circ}\) \(300^{\circ}\) \(315^{\circ}\) \(330^{\circ}\) \(\cos \left(\theta\right)\) \(\sin\left( \theta\right)\) \(\tan \left(\theta\right)\) -

Fill in the table from memory with exact values. Do you notice any patterns that might help you memorize the values?

\(\theta\) \(0^{\circ}\) \(30^{\circ}\) \(45^{\circ}\) \(60^{\circ}\) \(90^{\circ}\) \(\sin \left(\theta\right)\) \(\cos \left(\theta\right)\) \(\tan \left(\theta\right)\) -

Fill in the table from memory with decimal approximations to four places.

\(\theta\) \(0^{\circ}\) \(30^{\circ}\) \(45^{\circ}\) \(60^{\circ}\) \(90^{\circ}\) \(\sin \left(\theta\right)\) \(\cos \left(\theta\right)\) \(\tan \left(\theta\right)\) -

Complete the table with exact values.

\(\theta\) 0 \(30^{\circ}\) \(45^{\circ}\) \(60^{\circ}\) \(\sec \left(\theta\right)\) \(\csc \left(\theta\right)\) \(\cot \left(\theta\right)\)

For Problems 42 - 47, choose all values from the list below that are exactly equal to, or decimal approximations for, the given trigonometric ratio. (Try not to use a calculator!)\[\begin{array}{|ccccc|}

\hline \sin 30^{\circ} & \cos 45^{\circ} & \sin 60^{\circ} & \tan 45^{\circ} & \tan 60^{\circ} \\

0.5000 & 0.5774 & 0.7071 & 0.8660 & 1.0000 \\

\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{2}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{3}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{2} & \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \\

\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} & \frac{2}{\sqrt{3}} & \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} & \sqrt{3} & \frac{\sqrt{3}}{3} \\

\hline

\end{array}\nonumber\]

-

\(\cos 30^{\circ}\)

-

\(\sin 45^{\circ}\)

-

\(\tan 30^{\circ}\)

-

\(\cos 60^{\circ}\)

-

\(\sin 90^{\circ}\)

-

\(\cos 0^{\circ}\)

For Problems 48 - 55, evaluate. Give exact values.

-

\(\sin \left(30^{\circ}\right)\)

-

\(\cos \left(0^{\circ}\right)\)

-

\(\tan \left(45^{\circ}\right)\)

-

\(\sin \left(60^{\circ}\right)\)

-

\(\csc \left(30^{\circ}\right)\)

-

\(\sec \left(0^{\circ}\right)\)

-

\(\cot \left(45^{\circ}\right)\)

-

\(\csc \left(60^{\circ}\right)\)

For Problems 56 - 62, draw the angle in standard position, find a point on the terminal side of the angle, and find the value of all six trigonometric functions of the angle.

-

\( 150^{ \circ } \)

-

\( -90^{ \circ } \)

-

\( 225^{ \circ } \)

-

\( 180^{ \circ } \)

-

\( -300^{ \circ } \)

-

\( 90^{ \circ } \)

-

\( 315^{ \circ } \)

-

Explain why it makes sense that \(\sin 0^{\circ}=0\) and \(\sin 90^{\circ}=1\). Use a figure to illustrate your explanation.

-

Explain why it makes sense that \(\cos 0^{\circ}=1\) and \(\cos 90^{\circ}=0\). Use a figure to illustrate your explanation.

For Problems 65 - 70, state two possible quadrants where \( \theta \) could terminate.

-

\( \sin\left( \theta \right) = \dfrac{7}{12} \)

-

\( \cos\left( \theta \right) = -\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{9} \)

-

\( \tan\left( \theta \right) = -1.2 \)

-

\( \csc\left( \theta \right) = -3.87 \)

-

\( \sec\left( \theta \right) = \sqrt{2} \)

-

\( \cot\left( \theta \right) = \dfrac{3}{2} \)

In Problems 71 - 73, determine in which two quadrants is the statement true.

-

The sine is negative.

-

The cosine is negative.

-

The tangent is positive.

In Problems 74 - 77, state the quadrant(s) where \( \theta \) must terminate.

-

\( \sin\left( \theta \right) < 0\) and \( \cos\left( \theta \right) > 0 \)

-

\( \sec\left( \theta \right) > 0\) and \( \tan\left( \theta \right) < 0 \)

-

\( \csc\left( \theta \right) < 0\) and \( \cot\left( \theta \right) < 0 \)

-

\( \sin\left( \theta \right)\) and \( \cot\left( \theta \right) \) have the same sign

For Problems 78 - 85, find the values of the remaining trigonometric functions of \( \theta \) based on the given information.

-

\( \sin\left( \theta \right) = \dfrac{21}{29} \), where \( \theta \in \mathrm{QI} \)

-

\( \cos\left( \theta \right) = -\dfrac{3}{5} \), where \( \theta \in \mathrm{QIII} \)

-

\( \tan\left( \theta \right) = \dfrac{15}{8} \), where \( \theta \in \mathrm{QIII} \)

-

\( \csc\left( \theta \right) = -\dfrac{2}{\sqrt{3}} \), where \( \tan\left(\theta\right) > 0 \)

-

\( \sec\left( \theta \right) = \sqrt{2} \), where \( \theta \in \mathrm{QIV} \)

-

\( \cot\left( \theta \right) = -\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \), where \( \theta \in \mathrm{QII} \)

-

\( \sin\left( \theta \right) = -\dfrac{1}{4} \), where \( \cos\left(\theta\right) < 0 \)

-

\( \tan\left( \theta \right) = \dfrac{a}{b} \), where both \( a \) and \( b \) are positive

For Problems 86 - 88, find all angles between \(0^{\circ}\) and \(360^{\circ}\) for which the statement is true.

-

\(\cos \left(\theta\right) = -1\)

-

\(\sin \left(\theta\right) = -1\)

-

\(\tan \left(\theta\right) = -1\)

-

Find two angles, \(0 \leq \theta \leq 360^{\circ}\), with \(\sin \left(\theta\right) = 0\).

-

Find two angles, \(0 \leq \theta \leq 360^{\circ}\), with \(\cos \left(\theta\right) = 0\).

-

Find two angles, \(0 \leq \theta \leq 360^{\circ}\), with \(\sin \left(\theta\right) = -1\).

-

Find two angles, \(0 \leq \theta \leq 360^{\circ}\), with \(\cos \left(\theta\right) = -1\).

Synthesis Questions

For Problems 93 - 96, determine if the statement is true or false. Justify your response.

-

If \( \alpha < \beta\), then \( \sin\left( \alpha \right) < \sin\left( \beta \right)\).

-

If \( 0 \leq \alpha < \beta \leq 90^{ \circ }\), then \( \sin\left( \alpha \right) < \sin\left( \beta \right)\).

-

If \( 0 \leq \alpha < \beta \leq 90^{ \circ }\), then \( \cos\left( \alpha \right) < \cos\left( \beta \right)\).

-

If \( 0 \leq \alpha < \beta \leq 90^{ \circ }\), then \( \csc\left( \alpha \right) < \csc\left( \beta \right)\).

-

Is there an angle \( \theta \) such that \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = 3\)? Why or why not?

-

Is there an angle \( \theta \) such that \( \csc\left( \theta \right) = \frac{1}{5}\)? Why or why not?

-

Explain why \( \left| \cos\left( \theta \right) \right| \leq 1 \) for any angle \( \theta \).

-

Is it true that \(\tan \left(\theta\right) \leq 1\) for any angle \(\theta\)? Explain.

-

Use a sketch to explain why \(\cos 90^{\circ} = 0\).

-

Use a sketch to explain why \(\cos 180^{\circ}=1\).

In Problems 103 and 104, compare the given value with the trigonometric ratios of the special angles to answer the questions.

-

Is the acute angle larger or smaller than \(45^{\circ}\)?

-

\(\sin \alpha=0.7\)

-

\(\tan \beta=1.2\)

-

\(\cos \gamma=0.65\)

-

-

Is the acute angle larger or smaller than \(60^{\circ}\)?

-

\(\cos \theta=0.75\)

-

\(\tan \phi=1.5\)

-

\(\sin \psi=0.72\)

-

For Problems 105 - 108, describe what happens to the function values as \( \theta \) increases from \( 0^{ \circ } \) to \( 90^{ \circ } \).

-

\( \sin\left( \theta \right) \)

-

\( \cos\left( \theta \right) \)

-

\( \tan\left( \theta \right) \)

-

\( \csc\left( \theta \right) \)

-

Find two angles, \(0 \leq \theta \leq 360^{\circ}\), with \(\sin \left(\theta\right) = \cos \left(\theta\right)\).

-

Find two angles, \(0 \leq \theta \leq 360^{\circ}\), with \(\sin \left(\theta\right) = -\cos \left(\theta\right)\).

-

Explain why the definitions of the trigonometric ratios for a third-quadrant angle (between \(180^{\circ}\) and \(270^{\circ}\)) are independent of the point \(P\) chosen on the terminal side. Illustrate with a figure.

-

Explain why the definitions of the trigonometric ratios for a fourth-quadrant angle (between \(270^{\circ}\) and \(360^{\circ}\)) are independent of the point \(P\) chosen on the terminal side. Illustrate with a figure.

-

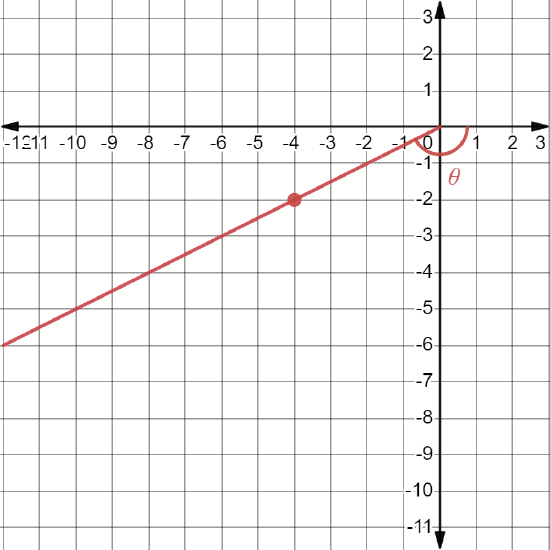

Find the values of all the trigonometric functions of \( \theta \) if the terminal side of \( \theta \) lies on the line \( y = 3x \) in \( \mathrm{QI} \).

-

Find the values of all the trigonometric functions of \( \theta \) if the terminal side of \( \theta \) lies on the line \( y = -\frac{1}{3}x \) in \( \mathrm{QII} \).

-

Find the values of all the trigonometric functions of \( \theta \) if the terminal side of \( \theta \) lies on the line \( y = \frac{4}{5}x \) in \( \mathrm{QIII} \).

-

Find the values of all the trigonometric functions of \( \theta \) if the terminal side of \( \theta \) lies on the line \( y = -6x \) in \( \mathrm{QIV} \).

For Problems 117 - 124, evaluate the expression for \(f(\theta)=\sin \theta\) and \(g(\theta)=\cos \theta\).

-

\(3+f\left(30^{\circ}\right)\)

-

\(3 f\left(30^{\circ}\right)\)

-

\(4 g\left(225^{\circ}\right)-1\)

-

\(-4+2 g\left(225^{\circ}\right)-1\)

-

\(-2 f(3 \theta)\), for \(\theta=90^{\circ}\)

-

\(6 f\left(\dfrac{\theta}{2}\right)\), for \(\theta=90^{\circ}\)

-

\(8-5 g\left(\dfrac{\theta}{3}\right)\), for \(\theta=360^{\circ}\)

-

\(1-4 g(4 \theta)\), for \(\theta=135^{\circ}\)

For Problems 125 - 130,

(a) Sketch an angle \(\theta\) in standard position, \(0^{\circ} \leq \theta \leq 180^{\circ}\), with the given properties.

(b) Find expressions for \(\cos \theta, \sin \theta\), and \(\tan \theta\) in terms of the given variable.

-

\(\cos \theta=\dfrac{x}{3}, x<0\)

-

\(\tan \theta=\dfrac{4}{\alpha}, \alpha<0\)

-

\(\theta\) is obtuse and \(\sin \theta=\dfrac{y}{2}\)

-

\(\theta\) is obtuse and \(\tan \theta=\dfrac{q}{-7}\)

-

\(\theta\) is obtuse and \(\tan \theta=m\)

-

\(\cos \theta=h\)