1.4: Circles and Angles in the Rectangular Coordinate System

- Page ID

- 145902

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

To succeed in this section, you'll need to use some skills from previous courses. While you should already know them, this is the first time they've been required. You can review these skills in CRC's Corequisite Codex. If you have a support class, it might cover some, but not all, of these topics.

The following is a list of learning objectives for this section.

|

.png?revision=1) To access the Hawk A.I. Tutor, you will need to be logged into your campus Gmail account. |

The Distance Formula

Matt is hiking in the Santa Monica mountains. He would like to know the distance from the Sycamore Canyon trailhead, located at \(12-\mathrm{C}\) on his map, to the Coyote Trail junction, located at \(8-\mathrm{F}\), as shown below.

Each interval on the map represents one kilometer. Matt remembers the Pythagorean Theorem and uses the map coordinates to label the sides of a right triangle. The distance he wants is the hypotenuse of the triangle, so\[\begin{array}{rrcl}

& d^2 & = & 4^2+3^2 \\

\implies & d^2 & = & 16 + 9 \\

\implies & d^2 & = & 25 \\

\implies & d & = & \sqrt{25} \\

\implies & d & = & 5 \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]The straight-line distance to Coyote junction is about 5 kilometers. The formula for the distance between two points is obtained similarly.

We first label a right triangle with points \(P_1\) and \(P_2\) on opposite ends of the hypotenuse (see Figure \( \PageIndex{ 2 } \)). The sides of the triangle have lengths \(|x_2 - x_1|\) and \(|y_2 - y_1|\). We can use the Pythagorean Theorem to calculate the distance between \(P_1\) and \(P_2\): \(d^2 = (x_2-x_1)^2 + (y_2 - y_1)^2\).

Taking the (positive) square root of each side of this equation gives us the Distance Formula.

Find the distance between (2, −1) and (4, 3).

- Solution

-

We substitute \((2,-1)\) for \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and \((4,3)\) for \(\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) in the Distance Formula to obtain

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 3 } \)

\[\begin{array}{rrrclcl}

& & d &=&\sqrt{\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2} & \quad & \left( \text{Distance Formula} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra}&\implies & & = & \sqrt{(4-2)^2+[3-(-1)]^2} & \quad & \left( \text{substitution} \right)\\

\scriptscriptstyle\mathrm{Arithmetic}&\implies & & = & \sqrt{2^2+4^2} & \quad & \left( \text{addition and subtraction} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\mathrm{Arithmetic}&\implies & & = & \sqrt{4 + 16} & \quad & \left( \text{applying powers} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\mathrm{Arithmetic}&\implies & & = & \sqrt{20} & \quad & \left( \text{addition} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\mathrm{Arithmetic}&\implies & & = & 2 \sqrt{5} & \quad & \left( \text{simplify the radical} \right)

\end{array} \nonumber \]The exact value of the distance, shown at right, is \(2 \sqrt{5}\) units. We obtain the same answer if we use \((4,3)\) for \(P_1\) and \((2,-1)\) for \(P_2\):\[ \begin{array}{rcl}

d & = & \sqrt{(2-4)^2+[(-1)-3]^2} \\[6pt]

& = & \sqrt{4+16} \\[6pt]

& = & \sqrt{20} \\[6pt]

& = & 2 \sqrt{5} \\[6pt]

\end{array} \nonumber \]We can use a calculator to obtain an approximation for this value and find \(2 \sqrt{5} \approx 2(2.236)=4.472 \).

In Example \( \PageIndex{ 1 } \), the radical \(\sqrt{4+16}\) cannot be simplified to \(\sqrt{4}+\sqrt{16}\). (Do you remember why not?)

- Find the distance between the points (−5, 3) and (3, −9).

- Plot the points on a Cartesian coordinate system and show how the Pythagorean Theorem is used to calculate the distance.

- Answers

-

- \(4\sqrt{13}\)

- The points (−5, 3) and (3, −9) are two vertices of a right triangle with one horizontal leg of length 8 and one vertical leg of length 12. The distance between (−5, 3) and (3, −9) is the hypotenuse \(c\).

Equation for a Circle

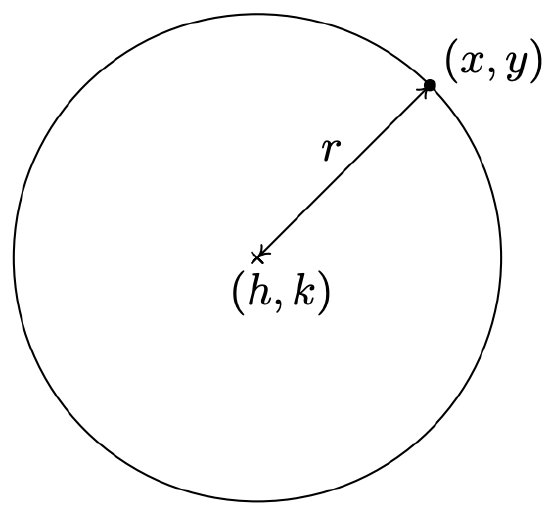

The Distance Formula is required for us to find the equation of a circle.

Find two points on the circle \(x^2+y^2=4\) with an \(x\)-coordinate of \(-1\).

- Solution

-

We substitute \(x=-1\) into the equation for the circle and solve for \(y\).\[\begin{array}{rrrclcl}

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & (-1)^2+y^2 & = & 4 & \quad & \left( \text{substitution} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\mathrm{Arithmetic} & \implies & 1 + y^2 & = & 4 & \quad & \left( \text{applying the power} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & y^2 & = & 3 & \quad & \left( \text{subtract }1\text{ from both sides} \right) \\

\scriptscriptstyle\xcancel{\mathrm{Arithmetic}} \to \mathrm{Algebra} & \implies & y & = & \pm\sqrt{3} & \quad & \left( \text{Extraction of Roots} \right) \\

\end{array}\nonumber \]Figure \( \PageIndex{ 4 } \)

The points are \((-1,\sqrt{3})\) and \((-1,\sqrt{3})\), as shown at right. Note that \(\sqrt{3} \approx 1.732\).

Find the coordinates of two points on the circle \(x^2 + y^2 = 1\) with \(y\)-coordinate \(\dfrac{1}{2}\).

- Answer

-

\(\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\right),\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\right)\)

The circle in Checkpoint \( \PageIndex{ 2} \) holds a special place in Trigonometry.

While the definition of the unit circle is only mentioned in passing here, it will become one of the foundational pieces of Trigonometry. We will revisit this later.

Later in this course, we will need to work with circles that do not have centers at the origin.

Write the standard equation of the circle with center \((-2,3)\) and radius \(5\).

- Solution

-

Here, \((h,k) = (-2,3)\) and \(r = 5\), so we get\[\begin{array}{rrcl}

& (x-(-2))^2+(y-3)^2 & = & (5)^2 \\

\implies & (x+2)^2+(y-3)^2 & = & 25 \\

\end{array}\nonumber\]

Graph \((x+2)^2+(y-1)^2 = 4\). Find the center and radius.

- Answer

-

From the standard form of a circle we have that \(x + 2\) is \(x-h\), so \(h = -2\) and \(y - 1\) is \(y - k\) so \(k = 1\). This tells us that our center is \((-2,1)\). Furthermore, \(r^2 = 4\), so \(r = 2\). Thus we have a circle centered at \((-2,1)\) with a radius of \(2\). Graphing gives us

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 5 } \)

Angles in the Cartesian Coordinate System

Now that we have reacquainted ourselves with angles, circles, and the Cartesian coordinate system, the next natural evolution toward Trigonometry is introducing angles to the Cartesian coordinate plane. Before we begin, however, it will be instrumental in this course to divide the Cartesian coordinate system into four sections, called quadrants.

Knowing this definition and understanding how the signs of \( x \) and \( y \) relate to these quadrants will be critical as we move forward.

Angles in Standard Position

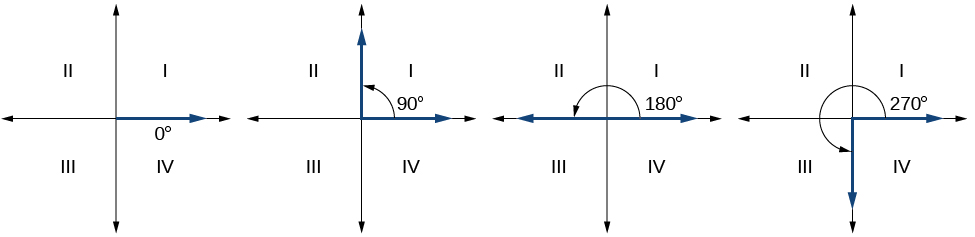

In general, and without worrying about a coordinate system, the degree measure of an angle depends only on the fraction of a whole rotation between its sides, not on the angle's location or position. To compare and analyze angles, we place them in standard position.

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 6 } \) below shows several angles moved into standard position.

The \( 320^{ \circ } \) in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 6 } \) has its terminal side in quadrant IV. We denote this as \( 320^{ \circ } \in \mathrm{QIV}\). Likewise, the remaining angles in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 6 } \) are listed as \( 240^{ \circ } \in \mathrm{QIII} \), \( 130^{ \circ } \in \mathrm{QII} \), and \( 55^{ \circ } \in \mathrm{QI} \).

Find the degree measure of each angle shown below, state the quadrant where the angle terminates, and sketch the angle in standard position.

- Solutions

-

- The angle \(\alpha\) is one-fifth of a complete revolution, or\[\dfrac{1}{5}(360^{\circ}) = 72^{\circ}.\nonumber \]In standard position, \( \alpha = 72^{ \circ } \in \mathrm{QI} \), as shown in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 8(a) } \) below.

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 8 } \)

- The angle \(\beta\) is \(\dfrac{11}{12}\) of a complete revolution, or\[\dfrac{11}{12}(360^{\circ}) = 330^{\circ}.\nonumber \]In standard position, \( \beta = 330^{ \circ } \in \mathrm{QIV} \). (See Figure \( \PageIndex{ 8(b) } \).)

- The angle \(\alpha\) is one-fifth of a complete revolution, or\[\dfrac{1}{5}(360^{\circ}) = 72^{\circ}.\nonumber \]In standard position, \( \alpha = 72^{ \circ } \in \mathrm{QI} \), as shown in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 8(a) } \) below.

Find the degree measure of each angle below, sketch the angle in standard position, and state the quadrant in which the angle terminates.

- Answers

-

- \(\theta = 120^{\circ} \in \mathrm{QII}\)

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 10 } \)

- \(\alpha = 250^{ \circ } - 180^{ \circ } = 70^{\circ} \in \mathrm{QI}\)

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 11 } \)

- \(\theta = 120^{\circ} \in \mathrm{QII}\)

Quadrantal Angles

Now that we are acquainted with angles in standard position, it's time we start classifying these angles by type. First up are the quadrantal angles.

For example, \( 270^{ \circ } \) has a terminal side on the negative \( y \)-axis. Therefore, we would call \( 270^{ \circ } \) a quadrantal angle. Figure \( \PageIndex{ 12 } \) illustrates a few quadrantal angles; however, as we will learn shortly, there are infinite quadrantal angles.

Negative Angles

Aligning with what we said earlier in this textbook, an angle is positive if it opens counterclockwise. If an angle opens clockwise, the angle is considered negative. For example, Figure \( \PageIndex{ 13 } \) shows the angle \( \alpha = -135^{ \circ } \), which terminates in \( \mathrm{QIII} \).

Graphing positive and negative angles in standard position will be a critical skill in Trigonometry.

Coterminal Angles

Because \(360^{\circ}\) represents one complete revolution, we can add or subtract a multiple of \(360^{\circ}\) to any angle and the terminal side of the resulting angle will arrive at the same position. For example, the angles \(70^{\circ}\) and \(430^{\circ}\) have the same terminal side because \(430^{\circ}=70^{\circ}+360^{\circ}\). Such angles are called coterminal.

The angle \(790^{\circ}\) is also coterminal with \(70^{\circ}\), because \(790^{\circ}=70^{\circ}+2\left(360^{\circ}\right)\) (see Figure \( \PageIndex{ 14 } \) below).

Coterminal angles need not be positive. For example, we could have been given \( \alpha = 140^{ \circ } \) and chosen to subtract \( 360^{ \circ } \) to get the coterminal angle \( -220^{ \circ } \) as shown in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 15 } \).

In fact, we could denote all angles coterminal to \( \alpha = 140^{ \circ } \) using the notation\[ 140^{ \circ } + 360^{ \circ }k, \text{ where } k \in \mathbb{Z}. \nonumber \]The symbol, \( \mathbb{Z} \), denotes the set of all integers (the set of numbers \( \ldots, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots \)). This notation gets used frequently in Mathematics from this point forward, so it is best to get used to it quickly.

Previously, we mentioned that the angles illustrated in Figure \( \PageIndex{ 12 } \) were only a "few quadrantal angles," implying there were more than what we listed. This was because, for example, given the quadrantal angle \( 90^{ \circ } \), we could generate an infinite number of other quadrantal angles with the same terminal side by considering\[ 90^{ \circ } + 360^{ \circ }k, \text{ where } k \in \mathbb{Z}. \nonumber \]Moreover, since the quadrantal angles only differ from each other by \( 90^{ \circ } \), we could generate all quadrantal angles with the single statement\[ 0^{ \circ } + 90^{ \circ }k, \text{ where } k \in \mathbb{Z}. \nonumber \]There is no need for the \( 0^{ \circ } \) angle in that formula, so we could shorten it up to just\[ 90^{ \circ }k, \text{ where } k \in \mathbb{Z}. \nonumber \]

Graph each of the angles below in standard position and classify them according to where their terminal side lies. Find three coterminal angles, at least one of which is positive and one of which is negative.

- \(\alpha = 60^{\circ}\)

- \(\beta = -225^{\circ}\)

- \(\gamma = 540^{\circ}\)

- \(\phi = -750^{\circ}\)

- Solutions

-

- To graph \(\alpha = 60^{\circ}\), we draw an angle with its initial side on the positive \(x\)-axis and rotate counter-clockwise \(\frac{60^{\circ}}{360^{\circ}} = \frac{1}{6}\) of a revolution. We see that \(\alpha\) is a Quadrant I angle. To find coterminal angles, we look for angles \(\theta\) of the form \(\theta = \alpha + 360^{\circ} \cdot k\), for some integer \(k\). When \(k = 1\), we get \(\theta = 60^{\circ} + 360^{\circ} = 420^{\circ}\). Substituting \(k = -1\) gives \(\theta = 60^{\circ} - 360^{\circ} = -300^{\circ}\). Finally, if we let \(k = 2\), we get \(\theta = 60^{\circ} + 720^{\circ} = 780^{\circ}\).

- Since \(\beta = - 225^{\circ}\) is negative, we start at the positive \(x\)-axis and rotate clockwise \(\frac{225^{\circ}}{360^{\circ}} = \frac{5}{8}\) of a revolution. We see that \(\beta\) is a Quadrant II angle. To find coterminal angles, we proceed as before and compute \(\theta = -225^{\circ} + 360^{\circ} \cdot k\) for integer values of \(k\). We find \(135^{\circ}\), \(-585^{\circ}\) and \(495^{\circ}\) are all coterminal with \(-225^{\circ}\).

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 16 } \)

- Since \(\gamma = 540^{\circ}\) is positive, we rotate counter-clockwise from the positive \(x\)-axis. One full revolution accounts for \(360^{\circ}\), with \(180^{\circ}\), or \(\frac{1}{2}\) of a revolution remaining. Since the terminal side of \(\gamma\) lies on the negative \(x\)-axis, \(\gamma\) is a quadrantal angle. All angles coterminal with \(\gamma\) are of the form \(\theta = 540^{\circ} + 360^{\circ} \cdot k\), where \(k\) is an integer. Working through the arithmetic, we find three such angles: \(180^{\circ}\), \(-180^{\circ}\) and \(900^{\circ}\).

- The Greek letter \(\phi\) is pronounced "fee" or "fie," and since \(\phi\) is negative, we begin our rotation clockwise from the positive \(x\)-axis. Two full revolutions account for \(720^{\circ}\), with just \(30^{\circ}\) or \(\frac{1}{12}\) of a revolution to go. We find that \(\phi\) is a Quadrant IV angle. To find coterminal angles, we compute \(\theta = -750^{\circ} + 360^{\circ} \cdot k\) for a few integers \(k\) and obtain \(-390^{\circ}\), \(-30^{\circ}\) and \(330^{\circ}\).

Figure \( \PageIndex{ 17 } \)

Find two angles coterminal with \(102^{\circ}\), one positive and one negative.

- Answer

-

\(462^{\circ},-258^{\circ}\)