7.1: The Fundamental Inverse Trigonometric Functions

- Page ID

- 145937

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)This section is designed assuming you understand the following topics from Algebra.

- Inverse Functions

- definition of one-to-one and invertible

- graphical interpretation

- finding the equation of an inverse given a function

- domain and range of a function and its inverse

- Horizontal Line Test

- Find the exact value of an inverse trigonometric function.

- Use technology to approximate the value of an inverse trigonometric function.

- Evaluate compositions involving trigonometric functions and inverse trigonometric functions.

- Simplify expressions involving trigonometric functions and inverse trigonometric functions.

In an earlier section, we introduced the idea of finding an acute angle given the value of a trigonometric function. We learned to use the calculator keys \( \mathrm{SIN}^{-1}, \mathrm{COS}^{-1}\), and \(\mathrm{TAN}^{-1}\) to find approximate values of \(\theta\) when we know either \(\sin \left(\theta\right), \cos \left(\theta\right)\), or \(\tan\left(\theta\right)\). For example, if we know that \(\cos\left(\theta\right)=0.3\), then the acute angle \( \theta \) is approximated by\[\theta=\cos^{-1}(0.3) \approx 1.2661 \text { radians }.\nonumber \]If you consider the initial piece of information, namely that \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = 0.3 \), this implies that we can use the \(\mathrm{SIN}^{-1}, \mathrm{COS}^{-1}\), and \(\mathrm{TAN}^{-1}\) keys to solve trigonometric equations (as long as the angle we are interested in is acute), just as we use square roots to solve quadratic equations.

Up to this point, that's all we needed to know about the inverse trigonometric functions; however, we will soon be solving more complex trigonometric equations, requiring a deeper discussion of them.

Does Every Function Have an Inverse?

Consider the function \(F(x)=x^2-4\). First, we'll find a formula for the inverse. We let \( y = F(x) \) and solve for \( x \)\[\begin{array}{rrcl}

& y & = & x^2-4 \\

\implies & y + 4 & = & x^2 \\

\implies & \pm\sqrt{y + 4} & = & x \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]We then interchange \(x\) and \(y\) to get \( y = \pm\sqrt{x + 4} \).

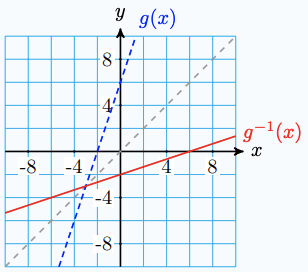

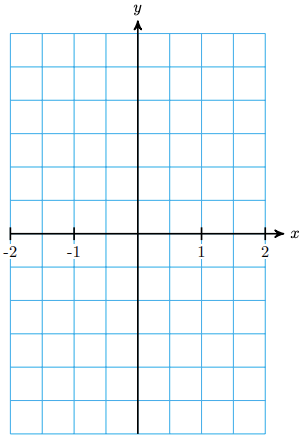

The graphs of \(F\) and its inverse, \( F^{-1}(x) = \pm \sqrt{x + 4} \), are shown below. You can see that although \(F\) is a function, its inverse is not because the graph of the inverse does not pass the Vertical Line Test.1

From Algebra, for a function, \( f \), to have an inverse that is also a function, we require \( f \) to pass the Horizontal Line Test. Recall that a function that passes the Horizontal Line Test is called one-to-one.

At this point, I want to be very clear about a few points:

- You can always find the inverse of a function graphically. All you need to do is go through each point on the graph of the function and swap the \( x \)- and \( y \)-coordinates. In doing so, the domain of your new graph is the old function's range, and the new graph's range is the old function's domain.

- It might be impossible to find the equation representing the inverse. For example, \( f(x) = e^x - 3x^2 + \sin(x) \) is definitely a function, but solving \( y = e^x - 3x^2 + \sin(x) \) for \( x \) is not going to happen.

- The inverse of a function need not be a function itself. We have just seen that \( F(x) = x^2 - 4 \) is an example of a function with an inverse that is not a function.

- If a function \( f \) passes the Horizontal Line Test, then the function is called one-to-one and its inverse is also a function that we call the inverse function of \( f \).

Despite knowing this from our Algebra, I want to repeat it in a theorem.

A function \( f \) has an inverse function if and only if \( f \) is one-to-one.

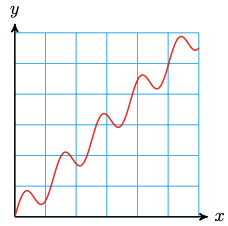

- Which of the graphs below represent functions?

- Which of the functions are one-to-one?

- Which of these functions have inverse functions?

- Solutions

-

- All three graphs pass the Vertical Line Test, so all three represent functions.

- Only the function represented by Graph II passes the Horizontal Line Test, so it is the only one-to-one function.

- Only function II is one-to-one, so it is the only function that has an inverse function.

Which of the functions below are one-to-one?

- Answer

-

I and III

Restricting the Domain: The Inverse Sine Function

Sometimes, it is so crucial that the inverse be a function that we are willing to sacrifice part of the original function to achieve this result.

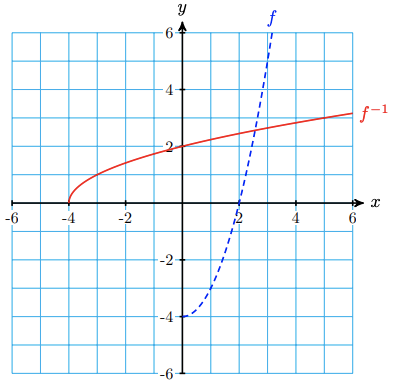

Look again at the graph of \(F(x)=x^2-4\). If we use only nonnegative \(x\)-values for the domain, we create a new function,\[f(x)=x^2-4, \quad x \geq 0.\nonumber \]The graph of this new function is shown as a dashed curve in the figure below.

The new function is one-to-one, and its inverse, \(f^{-1}(x)=\sqrt{x+4}\), is also a function.2

We say that we have restricted the domain of the original function, and we will use this technique to define inverse functions for the trigonometric functions.

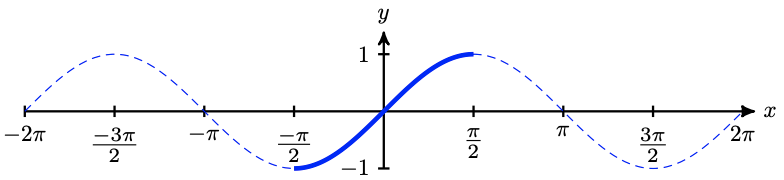

The sine function is not one-to-one; there are many angles that have the same sine value. In order to define its inverse function, we must restrict the domain of the sine to an interval on which the \(y\)-values do not repeat. But there are many candidates for such an interval; which one do we choose?

The most useful interval starts at \(x=0\) and moves as far as we can in either direction until the \(y\)-values begin to repeat. By doing so, we obtain the restricted domain \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq x \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\), as shown below. This piece of the function includes all of the original range values, from \(-1\) to \(1\).

Because the sine function is one-to-one in this domain, its inverse is a function.

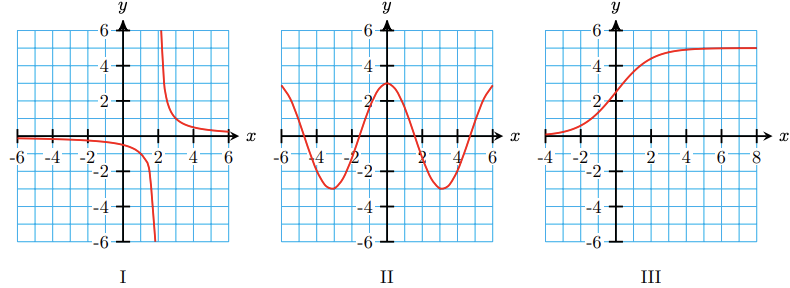

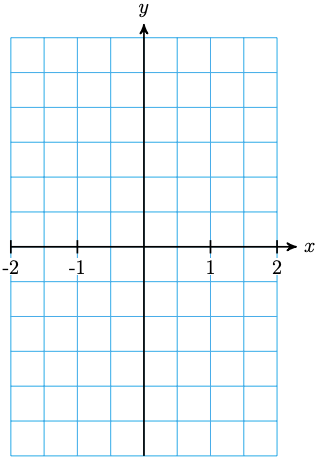

The graph of the inverse sine function, \(y=\sin ^{-1} \left(x\right)\), is shown below. Its domain is the same as the range of the sine function, namely \(-1 \leq x \leq 1\), and its range is our restricted domain for the sine, \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq y \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\).

The function \(f(x)=\sin ^{-1} \left(x\right)\) is defined as follows:\[\sin^{-1}\left(x\right)=\theta \quad \text{if and only if} \quad \sin\left(\theta\right) = x \quad \text{and} \quad -\dfrac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \dfrac{\pi}{2}. \nonumber \]

In other words, \(\sin ^{-1}\left(x\right)\) is the angle in radians between \(-\frac{\pi}{2}\) and \(\frac{\pi}{2}\), whose sine is \(x\). There are many angles with a given sine value \(x\), but only one of these angles can be \(\sin^{-1}\left(x\right)\). This is why the calculator's \(\mathrm{SIN}^{-1}\) key only returns angles between \(-\frac{\pi}{2}\) and \(\frac{\pi}{2}\).3

- If \(x=\sin \left(\theta\right)\) is positive, the inverse sine function delivers a first quadrant angle, \(0 \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\). This should make sense because all trigonometric functions are positive in the first quadrant.

- If \(x=\sin \left(\theta\right)\) is negative, the inverse sine function delivers a fourth quadrant angle, \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq 0\).

As the next example illustrates, when dealing with inverse trigonometric functions, we focus on finding the quadrant and the reference angle for the function.

Simplify each expression without using a calculator.

- \(\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\)

- \(\sin^{−1}\left(-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\)

- \( \sin^{-1}\left( \sin\left( \frac{5\pi}{6} \right) \right) \)

- \(\sin ^{-1}\left(\sin \left(\pi\right)\right)\)

- \( \sin\left( \sin^{-1}\left( 0.2 \right) \right) \)

- Solutions

-

- By definition, \(\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = \theta\) is an angle whose sine is \(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\), where \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\). That is, \(\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = \theta\) means \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \) and \( \theta \in \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right]\). While you might be able to quickly state the value of \(\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\) right now, we are going to take our time showcasing the thought process so that we can work with more complicated problems.

Quadrant: Because \(\sin \left(\theta\right) = -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) is negative, we further restrict \( \theta \) to the interval \( \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2},0 \right] \). In fact, since the value of the sine function is not \( \pm 1 \) or \( 0 \), we know \( \theta \) is not a quadrantal angle, so \( \theta \in \left( -\frac{\pi}{2}, 0 \right) \). Hence, \( \theta \in \mathrm{QIV} \).

Reference Angle: Since \(\sin \left(\frac{\pi}{3}\right) = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\), the reference angle for \(\theta\) is \(\hat{\theta} = \frac{\pi}{3}\).

Now that we have the quadrant and reference angle, we can state the value of \(\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\). \( \theta \in \left( -\frac{\pi}{2},0 \right) \) with a reference angle of \( \hat{\theta} = \frac{\pi}{3} \) means\[\sin^{-1}\left(-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)=-\dfrac{\pi}{3}.\nonumber \] - \(\sin^{−1}\left(-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right) = \theta\) means \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \) and \( \theta \in \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right] \).

Quadrant: Since the sine is negative, we need \( \theta \in \left(-\frac{\pi}{2} , 0\right)\).

Reference Angle: We know the reference angle for \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \) is \( \hat{\theta} = \frac{\pi}{4} \).

A reference angle of \( \frac{\pi}{4} \) in the interval \( \left( -\frac{\pi}{2},0 \right) \) means\[\sin^{−1}\left(−\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right)=−\dfrac{\pi}{4}.\nonumber \] - As promised, the method we used in parts (a) and (b) can be used for more complicated problems (like this one).

\( \sin^{-1}\left( \sin\left( \frac{5\pi}{6} \right) \right) = \theta\) means \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = \sin\left( \frac{5\pi}{6} \right) \) where \( \theta \in \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right] \). A lot of people would say that \( \theta \) must therefore be \( \frac{5\pi}{6} \); however, \( \frac{5\pi}{6} \) is not in the interval between \( -\frac{\pi}{2} \) and \( \frac{\pi}{2} \). Quadrants and reference angles to the rescue!

Quadrant: Since \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = \sin\left( \frac{5\pi}{6} \right) \) is positive (because \( \frac{5\pi}{6} \in \mathrm{QII} \)), \( \theta \in \left( 0, \frac{\pi}{2} \right)\). Hence, \( \theta \in \mathrm{QI} \).

Reference Angle: Since \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = \sin\left( \frac{5\pi}{6} \right) \), \( \theta \) must have the same reference angle as \( \frac{5\pi}{6} \). That is, \( \hat{\theta} = \frac{\pi}{6} \).

So, we know \( \theta \in \mathrm{QI} \) with a reference angle of \( \frac{\pi}{6} \). Hence,\[ \sin^{-1}\left( \sin\left( \dfrac{5\pi}{6} \right) \right) = \dfrac{\pi}{6}. \nonumber \] - \( \sin^{-1}\left( \sin\left( \pi \right) \right) = \theta \) means \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = \sin\left( \pi \right) \), where \( \theta \in \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right] \).

This is one of those moments where quadrants and reference angles will not work. This is because \( \pi \) is a quadrantal angle. In these cases, we simply evaluate \( \sin\left( \pi \right) = 0 \). Therefore, \(\sin ^{-1}\left(\sin \left(\pi\right)\right)=\sin^{-1}\left( 0\right)\). We want an angle whose sine is 0, and which lies in the interval \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\). This angle is \(0\). Therefore, \(\sin ^{-1}\left(\sin \left(\pi\right)\right)=0\).4 - We finally reach an example where the inverse trigonometric function is the argument of another function. Our approach will be the same as before - we start by focusing on the inverse trigonometric function.

\( \sin^{-1}\left( 0.2 \right) = \theta \) means \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = 0.2 \), where \( \theta \in \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right] \).

Believe it or not, we have actually found the value of \( \sin\left( \sin^{-1}\left( 0.2 \right) \right) \). Reread the statement above, and then follow the next line:\[ \sin\left( \sin^{-1}\left( 0.2 \right) \right) = \sin\left( \theta \right) = 0.2. \nonumber \]This illustrates the fact that\[ \sin\left( \sin^{-1}\left( r \right) \right) = r \nonumber \]as long as \( r \in \left[ -1,1 \right] \).

- By definition, \(\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = \theta\) is an angle whose sine is \(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\), where \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\). That is, \(\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = \theta\) means \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \) and \( \theta \in \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right]\). While you might be able to quickly state the value of \(\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\) right now, we are going to take our time showcasing the thought process so that we can work with more complicated problems.

The process we performed in Example \( \PageIndex{ 2 } \) is crucial to understand. It reinforces the statement, "Trigonometry is mostly about quadrants and reference angles."

When evaluating \( \sin^{-1}\left( r \right) \), where \( r \) is some number (often a ratio), we let the inverse equal \( \theta \) (this is to remind us that we are looking for an angle). That is, we begin by writing \( \sin^{-1}\left( r \right) = \theta \). In most cases, we are looking for a reference angle, \( \hat{\theta} \), such that \( \sin\left( \hat{\theta} \right) = |r| \). We use the sign of \( r \) to inform us as to which quadrant \( \theta \) is in. Once we have figured out these two details, we easily state the value of \( \theta \) (remembering the requirement that \( -\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2} \)).

Example \( \PageIndex{ 2d } \) showcases the exception to the "find the reference angle and quadrant" rule. If \( r \) is \( 0 \), \( 1 \), or \( -1 \), then we want an angle such that \( \sin\left( \theta \right) \) is equal to that value; however, these values are from quadrantal angles (\( 0 \), \( \frac{\pi}{2} \), and \( -\frac{\pi}{2} \), respectively). As such, we will not have a reference angle to find.

Finally, while Example \( \PageIndex{ 2e } \) illustrates that \( \sin\left( \sin^{-1}\left( r \right) \right) = r \) as long as \( r \in \left[ -1,1 \right] \), Examples \( \PageIndex{ 2c } \) and \( d \) give us the following caution.

\( \sin^{-1}\left( \sin\left( \theta \right) \right) \) is not necessarily \( \theta \).

The following theorem codifies the properties of the inverse sine function.

Properties of \( f(x) = \sin^{-1}(x) \):

- \( \theta = \sin^{-1}(x) \) if and only if \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = x \) where \( -\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2} \)

- Domain: \( \left[ -1,1 \right] \)

- Range: \( \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right] \)

- \( \sin\left( \sin^{-1}\left( x \right) \right) = x \) for all \( x \in \left[ -1,1 \right] \)

- \( \sin^{-1}\left( \sin\left( x \right) \right) = x \) provided \( x \in \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right] \)

Simplify each expression without using a calculator.

- \(\sin ^{-1}\left(\sin \left(\frac{\pi}{3}\right)\right)\)

- \(\sin ^{-1}\left(\sin \left(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\right)\)

- \( \sin\left( \sin^{-1}\left( -0.389 \right) \right) \)

- Answers

-

- \(\dfrac{\pi}{3}\)

- \(\dfrac{\pi}{3}\)

- \( -0.389 \)

The Inverse Cosine and Inverse Tangent Functions

The cosine and tangent functions are also periodic, so, just as with the sine function, to define their inverse functions we must restrict their domains to intervals where they are one-to-one. The graph of cosine is shown below.

Once again, the choice of these intervals is arbitrary. Suppose we start at \(\theta=0\) on the cosine graph. In that case, we can move in only one direction, either right or left, without encountering repeated \(y\)-values. As shown above, we choose to move in the positive direction to obtain the interval \(0 \leq \theta \leq \pi\). In this domain, the inverse of cosine is a function. Its graph is shown below.

The function \(f(x)=\cos ^{-1}\left(x\right)\) is defined as follows:\[\cos^{-1}\left(x\right)=\theta \quad \text{if and only if} \quad \cos\left(\theta\right)=x \quad \text{and} \quad 0 \leq \theta \leq \pi. \nonumber \]

The range of the inverse cosine function is \(0 \leq y \leq \pi\), so it delivers angles in the first and second quadrants. (Compare to the inverse sine, whose outputs are angles in the first or fourth quadrants.)

Properties of \( f(x) = \cos^{-1}(x) \):

- \( \theta = \cos^{-1}(x) \) if and only if \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = x \) where \( 0 \le \theta \le \pi \)

- Domain: \( \left[ -1,1 \right] \)

- Range: \( \left[ 0, \pi \right] \)

- \( \cos\left( \cos^{-1}\left( x \right) \right) = x \) for all \( x \in \left[ -1,1 \right] \)

- \( \cos^{-1}\left( \cos\left( x \right) \right) = x \) provided \( x \in \left[ 0, \pi \right] \)

Simplify each expression without using a calculator.

- \(\cos ^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\)

- \(\cos ^{-1}\left(\cos \left(\frac{7 \pi}{4}\right)\right)\)

- Solutions

-

- \(\cos^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = \theta\) means \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \), where \( \theta \in \left[ 0,\pi \right] \).

Quadrant: Since \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \) is negative, we further restrict \( \theta \) so that \( \theta \in \left( \frac{\pi}{2}, \pi \right) \). Thus, \( \theta \in \mathrm{QII} \).

Reference Angle: To find the reference angle, we ask ourselves what acute angle, \( \hat{\theta} \), results in\[ \cos\left( \hat{\theta} \right) = \left|-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \right| = \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}. \nonumber \]From our special triangles, we know this is \( \hat{\theta} = \frac{\pi}{6} \).

The angle in the second quadrant with this reference angle is \(\theta=\frac{5 \pi}{6}\), so\[\cos ^{-1}\left(-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)=\dfrac{5 \pi}{6}.\nonumber \] - \(\cos ^{-1}\left(\cos \left(\frac{7 \pi}{4}\right)\right) = \theta\) means \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = \cos\left( \frac{7\pi}{4} \right) \), where \( \theta \in \left[ 0,\pi \right] \).

Quadrant: Because \( \frac{7\pi}{4} \in \mathrm{QIV} \), we know that \(\cos\left( \theta \right) = \cos \left(\frac{7 \pi}{4}\right)\) is positive. Therefore, \( \theta \in \left( 0,\frac{\pi}{2} \right) \).

Reference Angle: Since \(\cos\left( \theta \right) = \cos \left(\frac{7 \pi}{4}\right)\), the reference angle for \( \theta \) must be equal to the reference angle for \( \frac{7\pi}{4} \). That is, \( \hat{\theta} = \frac{\pi}{4} \).

We have a reference angle of \( \frac{\pi}{4} \) in Quadrant I, this means\[\cos^{-1}\left(\cos \left(\dfrac{7 \pi}{4}\right)\right)=\dfrac{\pi}{4}.\nonumber \]

- \(\cos^{-1}\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = \theta\) means \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \), where \( \theta \in \left[ 0,\pi \right] \).

Let's take a moment to highlight an important takeaway from Example \( \PageIndex{ 3b } \). First, we know that the inverse trigonometric functions return angles. What part (b) of \( \PageIndex{ 3 } \) shows is that, given \( \cos^{-1}\left( \cos\left( \alpha \right) \right) = \theta \), the reference angle for both \( \theta \) and \( \alpha \) are the same. That is, we had \( \cos^{-1}\left( \cos\left( \frac{7\pi}{4} \right) \right) = \theta\). The reference angle for \( \frac{7\pi}{4} \) is \( \frac{\pi}{4} \), which is exactly the reference angle \( \hat{\theta} \).

This same principle holds for \( \sin^{-1}\left( \sin\left( \alpha \right) \right) = \theta \). Therefore, given \( \sin^{-1}\left( \sin\left( \frac{4\pi}{3} \right) \right) \), we know this will return an angle \( \theta \) such that \( \hat{\theta} = \frac{\pi}{3} \).

The reason for this common reference angle stems from the definition of the inverse trigonometric function,\[ \sin^{-1}\left( \sin\left( \alpha \right) \right) = \theta \quad \text{if and only if} \quad \sin\left( \theta \right) = \sin\left( \alpha \right). \nonumber \]Therefore, \( \hat{\alpha}\) must equal \(\hat{\theta} \).

Simplify \(\cos ^{-1}(-1)\) without using a calculator.

- Answer

-

\(\pi\)

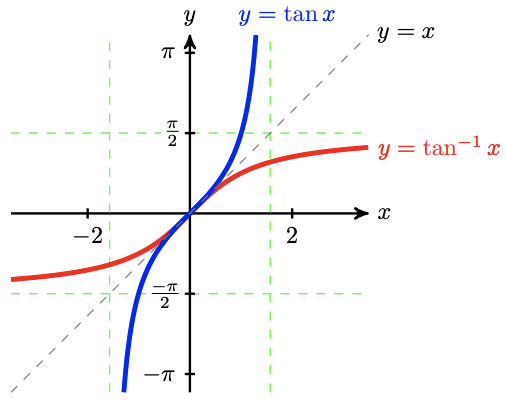

Finally, consider the graph of the tangent function. To choose a convenient interval on which the tangent is one-to-one, we start at \(x=0\) and move as far as we can in either direction along the \(x\)-axis. In this way, we obtain one cycle of the graph on the interval \(-\frac{\pi}{2}<\theta<\frac{\pi}{2}\), as shown below.

The range of the tangent on that interval includes all real numbers. Consequently, the domain of the inverse tangent function consists of all real numbers, and its range is the interval \(-\frac{\pi}{2}<y<\frac{\pi}{2}\). The graph of the inverse tangent function is shown below. Its outputs are angles in the first and fourth quadrants.

While you don't see the inverse sine and inverse cosine graphs in Mathematics beyond this point, the inverse tangent function graph is vital for Calculus concepts. This is a good one to be able to derive quickly.

The function \(f(x)=\tan ^{-1}\left(x\right)\) is defined as follows:\[\tan ^{-1}\left(x\right) = \theta \quad \text{if and only if} \quad \tan\left(\theta\right) = x \quad \quad \text{and} \quad -\dfrac{\pi}{2}<\theta<\dfrac{\pi}{2}. \nonumber \]

Properties of \( f(x) = \tan^{-1}(x) \):

- \( \theta = \tan^{-1}(x) \) if and only if \( \tan\left( \theta \right) = x \) where \( -\frac{\pi}{2} \lt \theta \lt \frac{\pi}{2} \)

- Domain: \( \left( -\infty,\infty \right) \)

- Range: \( \left( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \)

- As \( x \to -\infty \), \( \tan^{-1}(x) \to -\frac{\pi}{2} \), and as \( x \to \infty \), \( \tan^{-1}(x) \to \frac{\pi}{2} \)

- \( \tan\left( \tan^{-1}\left( x \right) \right) = x \) for all \( x \in \mathbb{R} \)

- \( \tan^{-1}\left( \tan\left( x \right) \right) = x \) provided \( x \in \left( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \)

Simplify each expression without using a calculator.

- \(\tan ^{-1}(-\sqrt{3})\)

- \(\tan ^{-1}\left(\tan\left(\dfrac{7 \pi}{4}\right)\right)\)

- Solutions

-

- \(\tan^{-1}(-\sqrt{3}) = \theta\) means \( \tan\left( \theta \right) = -\sqrt{3} \), where \( \theta \in \left( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \).

Quadrant: Since \( \tan\left( \theta \right) \) is negative, we further restrict the angle to \( \theta \in \left( -\frac{\pi}{2},0 \right) \), or Quadrant IV.

Reference Angle: Since \(\tan \left(\frac{\pi}{3}\right)=\sqrt{3}\), \( \hat{\theta} = \frac{\pi}{3} \).

Combining our results, we get\[\tan^{-1}(-\sqrt{3})=-\dfrac{\pi}{3}. \nonumber \] - \(\tan ^{-1}\left(\tan\left(\dfrac{7 \pi}{4}\right)\right) = \theta\) means \( \tan\left( \theta \right) = \tan\left( \frac{7\pi}{4} \right) \), where \( \theta \in \left( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \).

Quadrant: Because \(\frac{7 \pi}{4}\) is in Quadrant IV, \(\tan\left(\frac{7 \pi}{4}\right)\) is negative. Hence, \( \tan\left( \theta \right) \) is negative. As such, we further restrict the angle to \( \theta \in \left( -\frac{\pi}{2},0 \right) \).

Reference Angle: Since \( \tan\left( \theta \right) = \tan\left( \frac{7\pi}{4} \right) \), both arguments must share the same reference angle. Therefore, \( \hat{\theta} = \frac{\pi}{4} \).

Thus,\[\tan ^{-1}\left(\tan \left(\dfrac{7 \pi}{4}\right)\right)=-\dfrac{\pi}{4}.\nonumber \]

- \(\tan^{-1}(-\sqrt{3}) = \theta\) means \( \tan\left( \theta \right) = -\sqrt{3} \), where \( \theta \in \left( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \).

Simplify \(\tan ^{-1}(-1)\) without using a calculator.

- Answer

-

\(-\dfrac{\pi}{4}\)

Summary of Inverse Trigonometric Functions

Summarizing the inverse trigonometric functions and their properties before moving forward is helpful.

Key Concepts

Trigonometric functions take angles as arguments and return ratios. Inverse trigonometric functions take ratios as arguments and return (restricted) angles. That is,\[ \mathrm{trig}\left( \text{angle} \right) = \text{ratio} \quad \text{and} \quad \mathrm{trig}^{-1}\left( \text{ratio} \right) = \text{angle}. \nonumber \]To drive this point home, the rest of this summary uses \( r \) for "ratio" and \( \theta \) for the angle.

Basic Definitions

\[ \begin{array}{rcccr}

\sin^{-1}\left( r \right) = \theta & \text{ if and only if } & \sin\left( \theta \right) = r, & \text{ where } & -\dfrac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \dfrac{\pi}{2} \\

\\

\cos^{-1}\left( r \right) = \theta & \text{ if and only if } & \cos\left( \theta \right) = r, & \text{ where } & 0 \leq \theta \leq \pi \\

\\

\tan^{-1}\left( r \right) = \theta & \text{ if and only if } & \tan\left( \theta \right) = r, & \text{ where } & -\dfrac{\pi}{2} \lt \theta \lt \dfrac{\pi}{2} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

Domains and Ranges

\[ \begin{array}{c|c|ccc|c|c}

\textbf{Function} & \textbf{Domain} & \textbf{Range} & \quad & \textbf{Function} & \textbf{Domain} & \textbf{Range} \\

\hline r = \sin\left( \theta \right) & \theta \in \left( \infty,\infty \right) & r \in \left[ -1,1 \right] & \quad & \theta = \sin^{-1}\left( r \right) & r \in \left[ -1,1 \right] & \theta \in \left[ -\dfrac{\pi}{2}, \dfrac{\pi}{2} \right] \\

\\

r = \cos\left( \theta \right) & \theta \in \left( \infty,\infty \right) & r \in \left[ -1,1 \right] & \quad & \theta = \cos^{-1}\left( r \right) & r \in \left[ -1,1 \right] & \theta \in \left[ 0, \pi \right] \\

\\

r = \tan\left( \theta \right) & \theta \neq \dfrac{\pi}{2} + \pi k & r \in \left( -\infty,\infty \right) & \quad & \theta = \tan^{-1}\left( r \right) & r \in \left( -\infty,\infty \right) & \theta \in \left( -\dfrac{\pi}{2}, \dfrac{\pi}{2} \right) \\

\hline \end{array} \nonumber \]

Invertibility Properties

\[\begin{array}{rclcl}

\sin\left(\sin^{-1}\left(x\right)\right) & = & x & \quad & \text{for } -1\leq x\leq 1 \\

\cos\left(\cos^{-1}\left(x\right)\right) & = & x & \quad & \text{for } -1\leq x\leq 1\\

\tan\left(\tan^{-1}\left(x\right)\right) & = & x & \quad & \text{for } -\infty \lt x \lt \infty \\

\\

\sin^{-1}\left(\sin\left( x\right)\right) & = & x & \quad & \text{only for } -\dfrac{\pi}{2}\leq x\leq \dfrac{\pi}{2}\\

\cos^{-1}\left(\cos\left( x\right)\right) & = & x & \quad & \text{only for } 0\leq x\leq \pi \\

\tan^{-1}\left(\tan \left(x\right)\right) & = & x & \quad & \text{only for } -\dfrac{\pi}{2} \lt x \lt \dfrac{\pi}{2} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

Advice for Use

When asked to find the value of an inverse trigonometric function, \( \mathrm{trig}^{-1}\left( r \right) \), we start by recalling that the inverse trigonometric functions return angles. Therefore, we write\[ \mathrm{trig}^{-1}\left( r \right) = \theta. \nonumber \]Our goal is to find an appropriately restricted angle, \( \theta \), such that\[ \mathrm{trig}\left( \theta \right) = r. \nonumber \]A good piece of advice is to find the reference angle, \( \hat{\theta} \), by determining the value of\[ \mathrm{trig}^{-1}\left( |r| \right) = \hat{\theta} \nonumber \](Recall that all inverse trigonometric functions return angles in quadrant I if the argument of the inverse is positive.)

Once you have the reference angle, you can use the sign of \( r \) along with the knowledge of where your inverse trigonometric function returns angles to determine the value of \( \theta = \mathrm{trig}^{-1}\left( r \right). \)

The Invertibility Properties are tricky for most students. Just remember that the inverse trigonometric functions return restricted angles. That's why, for example, \( \cos^{-1}\left( \cos\left( x \right) \right) \) is not necessarily \( x \).

Using a Calculator to Evaluate Inverse Trigonometric Functions

We have been working with the inverse trigonometric buttons on your calculator for quite some time; however, it is important to clarify how they are used once you encounter negative ratios as arguments of inverse trigonometric functions.

Evaluate each of the following using a calculator. Your answers should be in radians.

- \( \sin^{-1}\left( 0.97 \right) \)

- \( \cos^{-1}\left( -0.561 \right) \)

- \( \tan^{-1}\left( -3 \right) \)

- Solutions

-

- This is a straightforward use of the calculator. At this point, you should be familiar enough with this to know we enter \( \mathrm{SIN}^{-1} \, 0.97 \) in the calculator to get approximately \(1.3252\) radians; however, we are going to use this to link back to the quadrant and reference angle concept we have been building throughout this section.

\( \sin^{-1}(0.97) = \theta \) means \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = 0.97 \), where \( \theta \in \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \right] \).

Quadrant: Since the sine is positive, we further restrict our angle to \( \theta \in \left( 0,\frac{\pi}{2} \right) \), or Quadrant I.

Reference Angle: The reference angle can be found by using your calculator (in radian mode) to evaluate \( \sin^{-1}\left( |0.97| \right) \approx 1.3252 \).

So our angle is in Quadrant I with a reference angle of \( \hat{\theta} \approx 1.3252 \). This means,\[ \sin^{-1}\left( 0.97 \right) \approx 1.3252. \nonumber \] - \( \cos^{-1}\left( -0.561 \right) = \theta \) means \( \cos\left( \theta \right) = -0.561 \), where \( \theta \in \left[ 0,\pi \right] \)

Quadrant: Since \( \cos\left( \theta \right) \) is negative, we can guarantee that \( \theta \in \mathrm{QII} \) (more specifically, \( \theta \in \left( \frac{\pi}{2},\pi \right) \)).

Reference Angle: To find the reference angle for \( \theta \), we compute \( \hat{\theta} = \cos^{-1}\left( |-0.561| \right) = \cos^{-1}\left( 0.561 \right) \approx 0.9752\) radians.

Now that we have a quadrant (II) and a reference angle (0.9752), we find the actual angle by subtracting the reference angle from \( \pi \). Thus,\[ \cos^{-1}\left( -0.561 \right) \approx \pi - 0.9752 \approx 2.1664. \nonumber \] - \( \tan^{-1}\left( -3 \right) = \theta \) means \( \tan\left( \theta \right) = -3 \), where \( \theta \in \left( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right) \).

Quadrant: Since the tangent is negative, we can restrict this interval to \( \theta \in \left(-\frac{\pi}{2}, 0\right) \), or Quadrant IV.

Reference Angle: The reference angle is\[ \hat{\theta} = \tan^{-1}\left( |-3| \right) = \tan^{-1}\left( 3 \right) \approx 1.2490. \nonumber \]

Thus,\[ \tan^{-1}\left( -3 \right) \approx -1.2490. \nonumber \]

- This is a straightforward use of the calculator. At this point, you should be familiar enough with this to know we enter \( \mathrm{SIN}^{-1} \, 0.97 \) in the calculator to get approximately \(1.3252\) radians; however, we are going to use this to link back to the quadrant and reference angle concept we have been building throughout this section.

I want to be clear, your calculator would have returned the answers to Example \( \PageIndex{ 5b } \) and \( \PageIndex{ 5c } \) if you had just entered \( \mathrm{COS}^{-1} \, -0.561 \) and \( \mathrm{TAN}^{-1} -3 \), respectively; however, as we move forward, your calculator will become less reliable when it comes to giving you the answer you're looking for. This is why I recommend evaluating the inverse trigonometric functions at their arguments' absolute value and treating the result as a reference angle. You honestly cannot go wrong if you do this.

Evaluate \({\cos}^{−1}(−0.4)\) using a calculator.

- Answer

-

\(1.9823\) radians or \(113.578^{\circ}\)

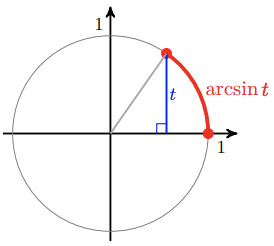

Alternate Notations

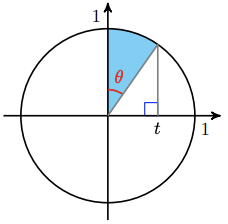

The inverse sine function, \(\sin^{-1} \left(x\right)\), is also called the arcsine function and denoted by \(\arcsin \left(x\right)\). (This terminology reminds us that the output of the inverse sine function is an angle, or the arc on a unit circle determined by that angle, as shown below.)

Similarly, the inverse cosine function is sometimes denoted by \(\arccos \left(x\right)\), and the inverse tangent function by \(\arctan \left(x\right)\).

Simplify each expression.

- \(\cos \left(\arccos \left(\frac{1}{3}\right)\right)\)

- \(\arcsin \left(\sin \left(\frac{3 \pi}{2}\right)\right)\)

- Solutions

-

- \(\arccos \left(\frac{1}{3}\right) = \theta\) means \(\cos \left(\theta\right)=\frac{1}{3}\), where \( 0 \leq \theta \leq \pi \). Since \( \frac{1}{3} \in \left[ -1,1 \right] \), we can use the Invertibility Property to state\[\cos \left(\arccos \left(\dfrac{1}{3}\right)\right)=\cos \left(\theta\right)=\dfrac{1}{3}.\nonumber \]

- \( \arcsin\left( \sin\left( \frac{3\pi}{2} \right) \right) = \theta \) means \( \sin\left( \theta \right) = \sin\left( \frac{3\pi}{2} \right) \), where \( -\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2} \). Noticing that \( \frac{3\pi}{2} \) is a quadrantal angle, we go ahead and simplify the right side of that last equation.\[ \sin\left( \theta \right) = \sin\left( \dfrac{3\pi}{2} \right) = -1 \nonumber \]Therefore, we require an angle between \( -\frac{\pi}{2} \) and \( \frac{\pi}{2} \) such that the sine of that angle is \( -1 \). This would be \( -\frac{\pi}{2} \).Thus,\[\arcsin \left(\sin \left(\dfrac{3 \pi}{2}\right)\right)=-\dfrac{\pi}{2}.\nonumber \]

Simplify each expression.

- \(\tan \left(\arctan \left(-\frac{5}{2}\right)\right)\)

- \(\arctan \left(\tan \left(-\frac{5 \pi}{6}\right)\right)\)

- Answers

-

- \(-\dfrac{5}{2}\)

- \(\dfrac{\pi}{6}\)

Up to this point, we have been very clear that the inverse trigonometric functions return angles; however, very technically, the arcfunctions return real numbers - not angles. This is why many instructors prefer you to answer in radians when dealing with arcfunctions rather than degrees. Fortunately, this is a subtlety that you don't have to worry about. You can assume the arcfunctions, like the inverse trigonometric functions, return angles if that helps you remember them.

Simplifying Expressions Involving Different Trigonometric Functions

The key to simplifying expressions involving inverse trigonometric functions is to remember that the inverse sine, cosine, or tangent of a number can be treated as an angle. It can often clarify the computations if we assign a name such as \(\theta\) or \(\phi\) to the inverse trigonometric value. Additionally, drawing triangles on the Cartesian coordinate system can be immensely helpful.

Evaluate \(\sin \left(\cos ^{-1} \left(\frac{3}{4}\right)\right)\).

- Solution

-

Notice this is a mixture of trigonometric functions. Our process changes only slightly from before.

We now can use this reference triangle to answer the question (i.e., there is no need to find the reference angle).

\(\cos ^{-1}\left( \frac{3}{4}\right) = \theta\) means \(\cos \left(\theta\right)= \frac{3}{4}\), where \( \theta \in \left[ 0,\pi \right] \).

Quadrant: Since the cosine of \( \theta \) is positive, we know \( \theta \in \mathrm{QI} \). Because we have a mixture of trigonometric functions, it's best to draw a reference triangle in \( \mathrm{QI} \).

\(\sin \left(\cos ^{-1} \left(\frac{3}{4}\right)\right)\) simplifies to \(\sin \left(\theta\right)\). Using the Pythagorean Theorem and the definition for sine, we get\[ \sin\left( \cos^{-1}\left( \dfrac{3}{4} \right) \right) = \sin\left( \theta \right) = \dfrac{\sqrt{7}}{4}. \nonumber \]

Evaluate \(\cos \left(\tan ^{-1} \left(\frac{2}{3}\right)\right)\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{3}{\sqrt{13}}\)

We can verify the results of the previous example using a calculator, but the same technique can be applied to simplify similar expressions involving variables.

Simplify \(\tan \left(\sin ^{-1} \left(x\right)\right)\), assuming that \(-1 \lt x \lt 0\).

- Solution

-

Let \(\theta=\sin ^{-1} (x)\), so that \(\sin \left(\theta\right)=x = \frac{x}{1}\), and the expression \(\tan \left(\sin ^{-1} \left(x\right)\right)=\tan \left(\theta\right)\). Since \( -1 \lt x \lt 0 \), sine is negative. Therefore, the inverse sine returns an angle in \( \mathrm{QIV} \). Specifically, \( -\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq 0 \). Drawing a reference triangle in \( \mathrm{QIV} \), we get

Now we the fact that \(\tan \left(\theta\right)\) is opposite over hypotenuse to get\[ \tan\left( \sin^{-1}\left( x \right) \right) = \tan\left( \theta \right) = \dfrac{x}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}. \nonumber \]

The answer to Example \( \PageIndex{ 8} \), \( \frac{x}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}} \), looks positive, but we know this cannot be the case because the tangent should be negative in \( \mathrm{QIV} \). Looks can be deceiving! While the denominator is definitely positive, the numerator, \( x \), is negative. Therefore, the answer is, in fact, negative!

Simplify \(\sin \left(\tan ^{-1} \left(z\right)\right)\), assuming that \(z \geq 0\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{z}{\sqrt{1+z^2}}\)

Simplifying Expressions Involving Identities

Now that we have learned all of the major identities in Trigonometry, we can use them with the inverse trigonometric functions. In doing so, we will demonstrate our fluency with inverse trigonometric functions and identities.

- Rewrite the following as an algebraic expression of \(x\) and state the domain on which the equivalence is valid.\[ f(x) = \cos\left(2 \arcsin(x)\right) \nonumber \]

- Find the exact value of the expression.\[ \sin\left( \cos^{-1}\left( -\dfrac{1}{3} \right) + \sin^{-1}\left( \dfrac{2}{5} \right) \right) \nonumber \]

- Solution

-

- We start by writing \(\theta = \arcsin(x)\) so that \(\theta\) lies in the interval \(\left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right]\) with \(\sin(\theta) = x\). We want to express \(\cos\left(2 \arcsin(x)\right) = \cos(2\theta)\) in terms of \(x\). Since \(\cos(2\theta)\) is defined everywhere, we get no additional restrictions on \(\theta\). We have three choices for rewriting \(\cos(2\theta)\):\[\cos^{2}(\theta) - \sin^{2}(\theta), \quad 2\cos^{2}(\theta) - 1, \quad \text{and} \quad 1 - 2\sin^{2}(\theta).\nonumber \]Since we know \(x = \sin(\theta)\), it is easiest to use the last form:\[\cos\left(2 \arcsin(x)\right) = \cos(2\theta) = 1 - 2\sin^{2}(\theta) = 1 - 2x^2.\nonumber\]To find the restrictions on \(x\), we consider our substitution, \(\theta = \arcsin(x)\). Since \(\arcsin(x)\) is defined only for \(-1 \leq x \leq 1\), the function, \(f(x) = \cos\left(2 \arcsin(x)\right) = 1-2x^2\), is valid only on \([-1,1]\).

- Let \( \alpha = \cos^{-1}\left( -\frac{1}{3} \right) \) and \( \beta = \sin^{-1}\left( \frac{2}{5} \right) \). Then we can rewrite the expression as\[ \sin\left( \cos^{-1}\left( -\dfrac{1}{3} \right) + \sin^{-1}\left( \dfrac{2}{5} \right) \right) = \sin\left( \alpha + \beta \right) = \sin\left( \alpha \right)\cos\left( \beta \right) + \cos\left( \alpha \right)\sin\left( \beta \right), \nonumber \]where\[ \cos\left( \alpha \right) = -\dfrac{1}{3}, \quad 0 \leq \alpha \leq \pi \nonumber \]and\[ \sin\left( \beta \right) = \dfrac{2}{5}, \quad -\dfrac{\pi}{2} \leq \beta \leq \dfrac{\pi}{2}. \nonumber \]Since \( \cos\left( \alpha \right) \) is negative, we immediately know \( \alpha \in \mathrm{QII} \). Moreover, \( \sin\left( \beta \right) \) being positive means that \( \beta \in \mathrm{QI} \). Drawing reference triangles, we get the following figures:

We now evaluate the equivalent expression, \( \sin\left( \alpha \right)\cos\left( \beta \right) + \cos\left( \alpha \right)\sin\left( \beta \right) \), using these reference triangles.\[ \begin{array}{rcl}

\sin\left( \cos^{-1}\left( -\dfrac{1}{3} \right) + \sin^{-1}\left( \dfrac{2}{5} \right) \right) & = & \sin\left( \alpha + \beta \right) \\

& = & \sin\left( \alpha \right)\cos\left( \beta \right) + \cos\left( \alpha \right)\sin\left( \beta \right) \\

& = & \left(\dfrac{2\sqrt{2}}{3}\right)\left( \dfrac{\sqrt{21}}{5} \right) + \left( -\dfrac{1}{3} \right)\left( \dfrac{2}{5} \right) \\

& = & \dfrac{2\sqrt{42}}{15} - \dfrac{2}{15} \\

& = & \dfrac{2 \sqrt{42} - 2}{15} \\

\end{array} \nonumber \]

Find the exact value of the expression.\[ \sin\left( 2\cos^{-1}\left( -\dfrac{1}{3} \right) \right) \nonumber \]

- Answer

-

\( - \dfrac{4\sqrt{2}}{9} \)

Modeling with Inverse Functions

The inverse trigonometric functions are used to model situations in which an angle is described in terms of one of its trigonometric ratios.

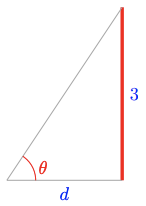

The bottom of a 3-meter-tall tapestry on a chateau wall is at your eye level. The angle \(\theta\) subtended vertically by the tapestry changes as you approach the wall.

- Express your distance from the wall, \(d\), as a function of \(\theta\).

- Express \(\theta\) as a function of \(d\).

- Solutions

-

- As shown below, we sketch the triangle formed by the tapestry and the lines of sight to its bottom and top. From the triangle we see that \(\tan \left(\theta\right)=\frac{3}{d}\), so \(d=\frac{3}{\tan \left(\theta\right)}\).

- Because \(\tan \left(\theta\right)=\frac{3}{d}, \theta=\tan ^{-1} \left(\frac{3}{d}\right)\).

- As shown below, we sketch the triangle formed by the tapestry and the lines of sight to its bottom and top. From the triangle we see that \(\tan \left(\theta\right)=\frac{3}{d}\), so \(d=\frac{3}{\tan \left(\theta\right)}\).

In Example \( \PageIndex{ 10 } \), we didn't have to worry about the quadrant in which \( \theta \) belongs. Most (but not all) applications share this quality. If we are looking at the top of a tapestry on a wall, and if the bottom of the tapestry is at eye level, no matter how close or how far we are away from the tapestry, the angle of inclination from eye level to the top of the tapestry will always be acute (i.e., a quadrant I angle).

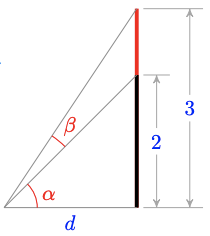

The tapestry from the previous example includes a 2-meter-tall unicorn with its feet at the bottom of the tapestry.

- Express \(\alpha\), the angle subtended vertically by the unicorn, as a function of \(d\), your distance to the tapestry.

- Express \(\beta\), the angle subtended by the portion of the tapestry above the unicorn, as a function of \(d\). (See the figure below).

- Answers

-

- \(\alpha=\tan ^{-1}\left(\dfrac{2}{d}\right)\)

- \(\beta=\tan ^{-1}\left(\dfrac{3}{d}\right)-\tan ^{-1}\left(\dfrac{2}{d}\right)\)

Footnotes

1 Recall that if a graph passes the Vertical Line Test, there is only one \(y\)-value for each value of \(x\).

2 We could also have used only negative \(x\)-values for the domain, or some smaller interval, just as long as the resulting function is one-to-one.

3 In this course, we have yet to consider inverse trigonometric functions returning angles other than acute (and, therefore, positive) ones.

4 It is also true that \(\sin \left(\pi\right)=0\), but \(\pi\) is not in the interval \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\).

Skills Refresher

Review the following skills you will need for this section.

For Problems 1 - 3, find the inverse of the function, if it exists.

-

\( f(x) = 2x^2 - 16x + 1 \)

-

\( g(x) = (x - 2)^3 \)

-

\( f(x) = \dfrac{3x - 1}{5x - 1} \)

For Problems 4 - 9,

(a) Find a formula for the inverse function.

(b) State the domain and range of the inverse function.

(c) Graph the function and its inverse on the same grid.

-

\(f(x) = \frac{1}{2}x - 4\)

-

\(g(x) = 3x + 6\)

-

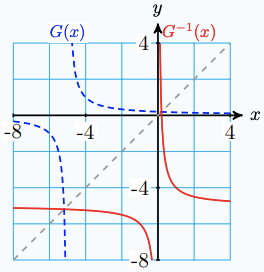

\(F(x) = 2 + \frac{1}{x}\)

-

\(G(x) = \frac{1}{x+5}\)

-

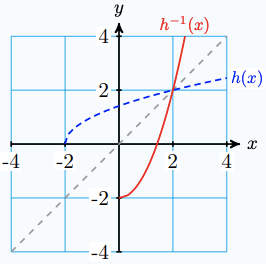

\(h(x) = \sqrt{x+2}\)

-

\(H(x) = 3 + \sqrt[3]{x}\)

For Problems 10 - 13, which functions have an inverse function? Explain your answer.

For Problems 14 - 17, use technology to graph the function and decide if it has an inverse function.

-

\(f(x)=\sin \left(2 x\right)-\cos \left(x\right)\)

-

\(g(x)=4 e^{-(x / 4)^2}\)

-

\(G(x)=\sqrt{25-x^2}\)

-

\(F(x)=\ln \left(x^3+8\right)\)

- Answers

-

-

No inverse exists for this function.

-

\( g^{-1}(x) = \sqrt[3]{x} + 2 \)

-

\( \dfrac{x - 1}{5x - 3} \)

-

-

\(f^{-1}(x)=2 x+8\)

-

Dom: \((-\infty, \infty)\) Rge: \((-\infty, \infty)\)

-

-

-

-

\(g^{-1}(x)=\dfrac{1}{3} x-2\)

-

Dom: \((-\infty, \infty)\) Rge: \((-\infty, \infty)\)

-

-

-

-

\(F^{-1}(x) = \dfrac{1}{x-2}\)

-

Dom: \(x \neq 0\) Rge: \(y \neq 2\)

-

-

-

-

\(G^{-1}(x)=\dfrac{1}{x}-5\)

-

Dom: \(x \neq -5\) Rge: \(y \neq 0\)

-

-

-

-

\(h^{-1}(x)=x^2-2\)

-

Dom: \(x \geq 0\) Rge: \(y \geq -2\)

-

-

-

-

\(H^{-1}(x) = (x-3)^3\)

-

Dom: \((-\infty, \infty)\) Rge: \((-\infty, \infty)\)

-

-

-

No. This graph does not pass the Horizontal Line Test.

-

Yes. This graph passes the Horizontal Line Test.

-

Yes. This graph passes the Horizontal Line Test.

-

No. This graph does not pass the Horizontal Line Test.

-

No.

-

No.

-

No.

-

Yes.

-

Homework

Concept Check

-

The following is a table of values defining a function \(f\). Make a table of values for \(f^{-1}\).

\(x\) -3 -2 0 1 4 \(f(x)\) 6 3 1 0 -1 -

What does it mean for a function to be one-to-one? Give an example.

-

Why do we restrict the domains of the trigonometric functions when we define their inverse functions?

-

Which of the following expressions is undefined? Why?

-

\(\cos ^{-1}(0)\)

-

\(\arctan (-2)\)

-

\(\arcsin (-2)\)

-

-

Use your calculator to evaluate \(\sin \left(118^{\circ}\right)\), then evaluate \(\sin ^{-1}\) of your answer. Explain the result.

-

-

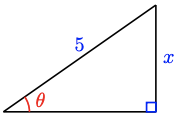

Write \(x\) as a function of \(\theta\).

-

Write \(\theta\) as a function of \(x\).

-

-

-

Write \(x\) as a function of \(\theta\).

-

Write \(\theta\) as a function of \(x\).

-

Basic Skills

For Problems 8 - 11,

(a) Evaluate each pair of angles to the nearest \(0.1\) radian, and show that they are supplements.

(b) Sketch both angles.

(c) Find the sine of each angle.

-

\(\theta=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{3}{4}\right), \phi=\cos ^{-1}\left(-\frac{3}{4}\right)\)

-

\(\theta=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{5}\right), \phi=\cos ^{-1}\left(-\frac{1}{5}\right)\)

-

\(\theta=\cos ^{-1}(0.1525), \quad \phi=\cos ^{-1}(-0.1525)\)

-

\(\theta=\cos ^{-1}(0.6825), \quad \phi=\cos ^{-1}(-0.6825)\)

For Problems 12 - 17, use a calculator to evaluate. Round your answers to the nearest tenth of a radian.

-

\(\sin ^{-1}(0.2838)\)

-

\(\tan ^{-1}(4.8972)\)

-

\(\cos ^{-1}(0.6894)\)

-

\(\arccos (-0.8134)\)

-

\(\arctan (-1.2765)\)

-

\(\arcsin (-07493)\)

For Problems 18 - 41, give exact values.

-

\(\cos ^{-1} \left(-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\)

-

\(\tan ^{-1}(-1)\)

-

\(\sin ^{-1} \left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)\)

-

\(\arccos \left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\)

-

\(\arctan \left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right)\)

-

\(\arcsin (-1)\)

-

\(\arccos \left( -1 \right)\)

-

\(\arctan \left( \sqrt{3} \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin \left( -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \right)\)

-

\(\arccos \left( -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \right)\)

-

\(\arctan \left( -\sqrt{3} \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin \left( -\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \right)\)

-

\(\arccos \left( 0 \right)\)

-

\(\arctan \left( 0 \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin \left( 0 \right)\)

-

\(\arccos \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)\)

-

\(\arctan \left( -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3} \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)\)

-

\(\arccos \left( \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \right)\)

-

\(\arctan \left( 1 \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin \left( \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin \left( \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin \left( 1 \right)\)

-

\(\arccos \left( 1 \right)\)

For Problems 42 - 56, without using a calculator, find the exact value or state that it is undefined.

-

\(\sin\left(\arcsin\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin\left(\arcsin\left(-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin\left(\arcsin\left(\dfrac{3}{5}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin\left(\arcsin\left(-0.42\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin\left(\arcsin\left(\dfrac{5}{4}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(\arccos\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(\arccos\left(-\dfrac{1}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(\arccos\left(\dfrac{5}{13}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(\arccos\left(-0.998\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(\arccos\left(\pi \right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan\left(\arctan\left(-1\right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan\left(\arctan\left(\sqrt{3}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan\left(\arctan\left(\dfrac{5}{12}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan\left(\arctan\left(0.965\right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan\left(\arctan\left( 3\pi \right)\right)\)

For Problems 57 - 77, find the exact value without using a calculator.

-

\(\tan \left(\sin ^{-1}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan \left(\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos \left[\tan ^{-1}(-2)\right]\)

-

\(\sin \left[\tan ^{-1}\left(-\frac{3}{\sqrt{5}}\right)\right]\)

-

\(\sin \left[\cos ^{-1}\left(-\frac{2 \sqrt{6}}{7}\right)\right]\)

-

\(\cos \left[\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{2}{7}\right)\right]\)

-

\(\sin\left(\arccos\left(-\dfrac{1}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin\left(\arccos\left(\dfrac{3}{5}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin\left(\arctan\left(-2\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(\arcsin\left(-\dfrac{5}{13}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(\arctan\left(\sqrt{7} \right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan\left(\arcsin\left(-\dfrac{2\sqrt{5}}{5}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan\left(\arccos\left(-\dfrac{1}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cot\left(\arcsin\left(\dfrac{12}{13}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cot\left(\arccos\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cot\left(\arctan \left( 0.25 \right)\right)\)

-

\(\sec\left(\arccos\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sec\left(\arcsin\left(-\dfrac{12}{13}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sec\left(\arctan\left(10\right)\right)\)

-

\(\csc\left(\arcsin\left(\dfrac{3}{5}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\csc\left(\arctan\left(-\dfrac{2}{3}\right)\right)\)

For Problems 78 - 86, simplify the expression and state the domain on which the equivalence is valid.

-

\(\tan \left(\cos ^{-1} (x)\right)\)

-

\(\cos \left(\sin ^{-1} (h)\right)\)

-

\(\sin \left( \arccos \left( x \right) \right)\)

-

\(\cos \left( \arctan \left( x \right) \right)\)

-

\(\tan \left( \arcsin \left( x \right) \right)\)

-

\(\sec \left( \arctan \left( x \right) \right)\)

-

\(\csc \left( \arccos \left( x \right) \right)\)

-

\(\sin \left(\tan ^{-1} (2 t)\right)\)

-

\(\tan \left(\sin ^{-1} (3 b)\right)\)

For Problems 87 - 101, find the exact value or state that it is undefined.

-

\(\arcsin\left(\sin\left(\dfrac{\pi}{6}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin\left(\sin\left(-\dfrac{\pi}{3}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin\left(\sin\left(\dfrac{3\pi}{4}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin\left(\sin\left(\dfrac{11\pi}{6}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arcsin\left(\sin\left(\dfrac{4\pi}{3}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arccos\left(\cos\left(\dfrac{\pi}{4}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arccos\left(\cos\left(\dfrac{2\pi}{3}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arccos\left(\cos\left(\dfrac{3\pi}{2}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arccos\left(\cos\left(-\dfrac{\pi}{6}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arccos\left(\cos\left(\dfrac{5\pi}{4}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arctan\left(\tan\left(\dfrac{\pi}{3}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arctan\left(\tan\left(-\dfrac{\pi}{4}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arctan\left(\tan\left(\pi\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arctan\left(\tan\left(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\arctan\left(\tan\left(\dfrac{2\pi}{3}\right) \right)\)

For Problems 102 - 104, complete the table of values and sketch the function.

-

\(x\) -1 \(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) \(-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) \(-\frac{1}{2}\) 0 \(\frac{1}{2}\) \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) 1 \(\cos ^{-1} x\)

-

\(x\) -1 \(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) \(-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) \(-\frac{1}{2}\) 0 \(\frac{1}{2}\) \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) 1 \(\sin ^{-1} x\)

-

\(x\) \(-\sqrt{3}\) -1 \(-\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\) 0 \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\) 1 \(\sqrt{3}\) \(\tan ^{-1} x\)

-

Use a graphing calculator to answer each of the following questions. Then explain the results.

-

Does \(\cos ^{-1} (x)=\frac{1}{\cos (x)}\)?

-

Does \(\sin ^{-1} (x)=\frac{1}{\sin (x)}\)?

-

Does \(\tan ^{-1} (x)=\frac{1}{\tan (x)}\)?

-

-

-

Sketch a graph of \(y=\cos ^{-1} (x)\), and label the scales on the axes.

-

Use transformations to sketch graphs of \(y=2 \cos ^{-1} (x)\) and \(y=\cos ^{-1}(2 x)\).

-

Does \(2 \cos ^{-1} (x)=\cos ^{-1}(2 x)\)?

-

-

-

Sketch a graph of \(y=\sin ^{-1} (x)\), and label the scales on the axes.

-

Use transformations to sketch graphs of \(y=\frac{1}{2} \sin ^{-1} (x)\) and \(y=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{2} x\right)\).

-

Does \(\frac{1}{2} \sin ^{-1} (x)=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{2} x\right)\)?

-

-

-

Sketch a graph of \(y=\tan ^{-1} (x)\), and label the scales on the axes.

-

Use your calculator to graph \(y=\frac{\sin ^{-1} (x)}{\cos ^{-1} (x)}\) on a suitable domain.

-

Does \(\tan ^{-1} (x)=\frac{\sin ^{-1} (x)}{\cos ^{-1} (x)}\)?

-

-

-

Use your calculator to sketch \(y=\sqrt[3]{x}\) and \(\tan ^{-1} (x)\) on \([-10,10]\).

-

Describe the similarities and differences in the two graphs.

-

For Problems 110 - 121, find the exact value for the expression.

-

\(\sin\left(\arcsin\left( \dfrac{5}{13} \right) + \dfrac{\pi}{4}\right)\)

-

\(\tan\left( \arctan(3) + \arccos\left(-\dfrac{3}{5}\right) \right)\)

-

\(\sin\left(2\arcsin\left(-\dfrac{4}{5}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin\left(2\arctan\left(2\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(2 \arcsin\left(\dfrac{3}{5}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin\left( \dfrac{\arctan(2)}{2} \right)\)

-

\(\sin \left(2 \tan ^{-1} (4)\right)\)

-

\(\cos \left(2 \sin ^{-1}\left(\frac{5}{13}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan \left(2 \cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin \left(2 \cos ^{-1}\left(-\frac{4}{5}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\tan \left(2 \sin ^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos \left(2 \tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

Let \(\alpha = \cos ^{-1} \left(-\frac{4}{5}\right), \beta = \sin ^{-1} \left(\frac{5}{13}\right)\). Find exact values for the following.

-

\(\cos (\alpha + \beta )\)

-

\(\sin (\alpha + \beta )\)

-

\(\cos (\alpha - \beta )\)

-

\(\sin (\alpha - \beta )\)

-

-

Let \(\alpha = \sin ^{-1} \left(-\frac{15}{17}\right), \beta = \tan ^{-1} \left(\frac{4}{3}\right)\). Find exact values for the following.

-

\(\cos (\alpha + \beta )\)

-

\(\sin (\alpha + \beta )\)

-

\(\cos (\alpha - \beta )\)

-

\(\sin (\alpha - \beta )\)

-

-

Find an exact value for \(\sin \left(\tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)+\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{4}{5}\right)\right)\).

-

Find an exact value for \(\cos \left(\tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{5}{12}\right)+\sin ^{-1}\left(-\frac{3}{5}\right)\right)\).

For Problems 126 - 141, rewrite the expression as an algebraic expression without trigonometric functions.

-

\(\sin \left(2 \tan ^{-1} (x)\right)\)

-

\(\cos \left(2 \sin ^{-1} (x)\right)\)

-

\(\sin \left(2 \cos ^{-1} (w)\right)\)

-

\(\cos \left(2 \tan ^{-1} (w)\right)\)

-

\(\sin(\arccos(2x))\)

-

\(\sin\left(\arccos\left(\dfrac{x}{5}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(\arcsin\left(\dfrac{x}{2}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\cos\left(\arctan\left(3x\right)\right)\)

-

\(\sin(2\arcsin(7x))\)

-

\(\sin\left(2 \arcsin\left( \dfrac{x\sqrt{3}}{3} \right) \right)\)

-

\(\cos(2 \arcsin(4x))\)

-

\(\sec(\arctan(2x))\tan(\arctan(2x))\)

-

\(\sin \left( \arcsin(x) + \arccos(x) \right)\)

-

\(\cos \left( \arcsin(x) + \arctan(x) \right)\)

-

\(\tan \left( 2\arcsin(x) \right)\)

-

\(\sin \left( \dfrac{1}{2}\arctan(x) \right)\)

-

If \(x=5 \sin (\theta), 0^{\circ}<\theta<90^{\circ}\), express \(\sin (2 \theta)\) and \(\cos (2 \theta)\) in terms of \(x\).

-

If \(x-1=2 \cos (\theta), 0^{\circ}<\theta<90^{\circ}\), express \(\sin (2 \theta)\) and \(\cos (2 \theta)\) in terms of \(x\).

-

If \(x=3 \tan (\theta)\), write \(\theta+\frac{1}{4} \sin (2 \theta)\) in terms of \(x\).

-

If \(x=5 \cos (\theta)\), write \(\frac{\theta}{2}-\cos (2 \theta)\) in terms of \(x\).

-

If \(\sin(\theta) = \dfrac{x}{2}\) for \(-\dfrac{\pi}{2} < \theta < \dfrac{\pi}{2}\), find an expression for \(\theta + \sin(2\theta)\) in terms of \(x\).

-

If \(\tan(\theta) = \dfrac{x}{7}\) for \(-\dfrac{\pi}{2} < \theta < \dfrac{\pi}{2}\), find an expression for \(\dfrac{1}{2}\theta - \dfrac{1}{2}\sin(2\theta)\) in terms of \(x\).

-

If \(\sec(\theta) = \dfrac{x}{4}\) for \(0 < \theta < \dfrac{\pi}{2}\), find an expression for \(4\tan(\theta) - 4\theta\) in terms of \(x\).

-

-

For what values of \(x\) is the function \(f(x)=\sin (\arcsin (x))\) defined?

-

Is \(\sin (\arcsin (x))=x\) for all \(x\) where it is defined? If not, for what values of \(x\) is the equation false?

-

For what values of \(x\) is the function \(g(x)=\arcsin (\sin (x))\) defined?

-

Is \(\arcsin (\sin (x))=x\) for all \(x\) where it is defined? If not, for what values of \(x\) is the equation false?

-

-

-

For what values of \(x\) is the function \(f(x)=\cos (\arccos (x))\) defined?

-

Is \(\cos (\arccos (x))=x\) for all \(x\) where it is defined? If not, for what values of \(x\) is the equation false?

-

For what values of \(x\) is the function \(g(x)=\arccos (\cos (x))\) defined?

-

Is \(\arccos (\cos (x))=x\) for all \(x\) where it is defined? If not, for what values of \(x\) is the equation false?

-

Synthesis Questions

For Problems 151 - 155, state the domain of the function.

-

\(f(x) = \arcsin(5x)\)

-

\(f(x) = \arccos\left(\dfrac{3x-1}{2} \right)\)

-

\(f(x) = \arcsin\left(2x^2\right)\)

-

\(f(x) = \arccos\left(\dfrac{1}{x^2-4}\right)\)

-

\(f(x) = \arctan(4x)\)

Applications

For Problems 156 - 161, sketch a figure to help you model each problem.

-

Ivan is watching the launch of a satellite at Cape Canaveral. The viewing area is 500 yards from the launch site. The angle of elevation, \(\theta\), of Ivan's line of sight increases as the booster rocket rises.

-

Write a formula for the height, \(h\), of the rocket as a function of \(\theta\).

-

Write a formula for \(\theta\) as a function of \(h\).

-

Evaluate the formula in part (b) for \(h=1000\), and interpret the result.

-

-

Camille's house lies under the flight path from the city airport, and commercial airliners pass overhead at an altitude of 15,000 feet. As Camille watches an airplane recede, its angle of elevation, \(\theta\), decreases.

-

Write a formula for the horizontal distance, \(d\), to the airplane as a function of \(\theta\).

-

Write a formula for \(\theta\) as a function of \(d\).

-

Evaluate the formula in part (b) for \(d=20,000\), and interpret the result.

-

-

While driving along the interstate, you approach an enormous 50-foot-wide billboard that sits just beside the road. Your viewing angle, \(\theta\), increases as you get closer to the billboard.

-

Write a formula for your distance, \(d\), from the billboard as a function of \(\theta\).

-

Write a formula for \(\theta\) as a function of \(d\).

-

Evaluate the formula in part (b) for \(d=200\), and interpret the result.

-

-

Sang is walking along the bank of a straight river toward a 20-meter-long bridge over the river. Let \(\theta\) be the angle subtended horizontally by Sang's view of the bridge.

-

Write a formula for Sang's distance from the bridge, \(d\), as a function of \(\theta\).

-

Write a formula for \(\theta\) as a function of \(d\).

-

Evaluate the formula in part (b) for \(d=500\), and interpret the result.

-

-

Wyatt is viewing a 4-meter tall painting whose base is 1 meter above his eye level.

-

Write a formula for \(\alpha\), the angle subtended from Wyatt's eye level to the bottom of the painting, when he stands \(x\) meters from the wall.

-

Write a formula for \(\beta\), the angle subtended by the painting, in terms of \(x\).

-

Evaluate the formula in part (b) for \(x=5\), and interpret the result.

-

-

A 5-foot-tall mirror is positioned so that its bottom is 1.5 feet below Kim's eye level.

-

Write a formula for \(\alpha\), the angle subtended by the section of the mirror below Kim's eye level, when she stands \(x\) feet from the mirror.

-

Write a formula for \(\theta\), the angle subtended by the entire mirror, in terms of \(x\).

-

Evaluate the formula in part (b) for \(x = 10\), and interpret the result.

-

Challenge Problems

-

Use your calculator to graph \(y=\sin ^{-1} (x)+\cos ^{-1} (x)\).

-

State the domain and range of the graph.

-

Explain why the graph looks as it does.

-

-

Use your calculator to graph \(y=\tan ^{-1} (x)+\tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\).

-

State the domain and range of the graph.

-

Explain why the graph looks as it does.

-

-

Show that \(\arcsin(x) + \arccos(x) = \dfrac{\pi}{2}\) for \(-1 \leq x \leq 1\).

In Problems 165 and 166, we find a formula for the area under part of a semicircle.

-

Use the figure of a unit circle to answer the following.

-

Write an expression for the area of the shaded sector in terms of \(\theta\).

-

How are \(\theta\) and \(t\) related in the figure? (Hint: Write an expression for \(\sin (\theta)\).)

-

Combine your answers to (a) and (b) to write an expression for the area of the sector in terms of \(t\).

-

-

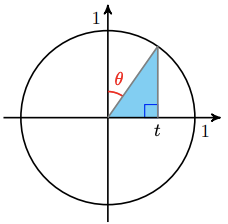

Use the figure of a unit circle to answer the following.

-

Write an expression for the height of the shaded triangle in terms of \(t\). (Hint: Use the Pythagorean Theorem.)

-

Write an expression for the area of the triangle in terms of \(t\).

-

Combine your answers to (b) and to the previous problem to write an expression for the area bounded above by the upper semicircle, below by the \(x\)-axis, on the left by the \(y\)-axis, and on the right by \(x=t\), when \(0 \leq t \leq 1\).

-

-

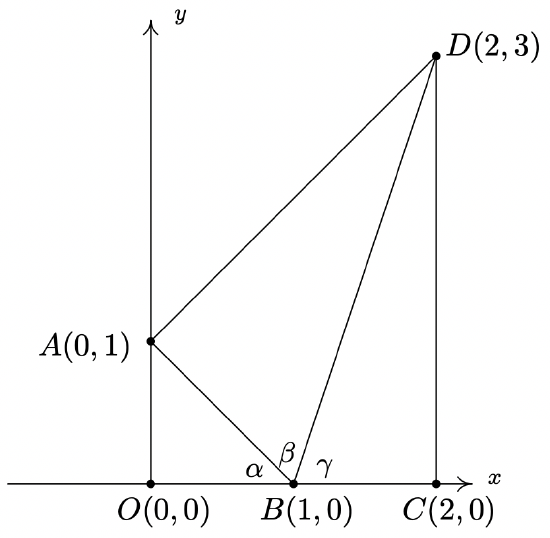

Use the following picture and the series of exercises on the next page to show that \[\arctan(1) + \arctan(2) + \arctan(3) = \pi\nonumber\]

-

Clearly \(\triangle AOB\) and \(\triangle BCD\) are right triangles because the line through \(O\) and \(A\) and the line through \(C\) and \(D\) are perpendicular to the \(x\)-axis. Use the distance formula to show that \(\triangle BAD\) is also a right triangle (with \(\angle BAD\) being the right angle) by showing that the sides of the triangle satisfy the Pythagorean Theorem.

-

Use \(\triangle AOB\) to show that \(\alpha = \arctan(1)\)

-

Use \(\triangle BAD\) to show that \(\beta = \arctan(2)\)

-

Use \(\triangle BCD\) to show that \(\gamma = \arctan(3)\)

-

Use the fact that \(O\), \(B\) and \(C\) all lie on the \(x\)-axis to conclude that \(\alpha + \beta + \gamma = \pi\). Thus \(\arctan(1) + \arctan(2) + \arctan(3) = \pi\).

-