Identify Multiples of Numbers

Annie is counting the shoes in her closet. The shoes are matched in pairs, so she doesn’t have to count each one. She counts by twos: \(2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12\). She has \(12\) shoes in her closet.

The numbers \(2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12\) are called multiples of \(2\). Multiples of \(2\) can be written as the product of a counting number and \(2\). The first six multiples of \(2\) are given below.

\[\begin{split} 1 \cdot 2 & = 2 \\ 2 \cdot 2 & = 4 \\ 3 \cdot 2 & = 6 \\ 4 \cdot 2 & = 8 \\ 5 \cdot 2 & = 10 \\ 6 \cdot 2 &= 12 \end{split} \nonumber \]

A multiple of a number is the product of the number and a counting number. So a multiple of \(3\) would be the product of a counting number and \(3\). Below are the first six multiples of \(3\).

\[\begin{split} 1 \cdot 3 & = 3 \\ 2 \cdot 3 & = 6 \\ 3 \cdot 3 & = 9 \\ 4 \cdot 3 & = 12 \\ 5 \cdot 3 & = 15 \\ 6 \cdot 3 &= 18 \end{split} \nonumber \]

We can find the multiples of any number by continuing this process. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows the multiples of \(2\) through \(9\) for the first twelve counting numbers.

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)

| Counting Number |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

| Multiples of 2 |

2 |

4 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

12 |

14 |

16 |

18 |

20 |

22 |

24 |

| Multiples of 3 |

3 |

6 |

9 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

21 |

24 |

27 |

30 |

33 |

36 |

| Multiples of 4 |

4 |

8 |

12 |

16 |

20 |

24 |

28 |

32 |

36 |

40 |

44 |

48 |

| Multiples of 5 |

5 |

10 |

15 |

20 |

25 |

30 |

35 |

40 |

45 |

50 |

55 |

60 |

| Multiples of 6 |

6 |

12 |

18 |

24 |

30 |

36 |

42 |

48 |

54 |

60 |

66 |

72 |

| Multiples of 7 |

7 |

14 |

21 |

28 |

35 |

42 |

49 |

56 |

63 |

70 |

77 |

84 |

| Multiples of 8 |

8 |

16 |

24 |

32 |

40 |

48 |

56 |

64 |

72 |

80 |

88 |

96 |

| Multiples of 9 |

9 |

18 |

27 |

36 |

45 |

54 |

63 |

72 |

81 |

90 |

99 |

108 |

Definition: Multiple of a Number

A number is a multiple of \(n\) if it is the product of a counting number and \(n\).

Recognizing the patterns for multiples of \(2\), \(5\), \(10\), and \(3\) will be helpful to you as you continue in this course.

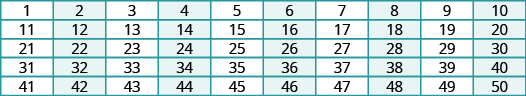

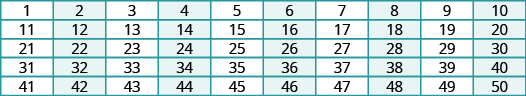

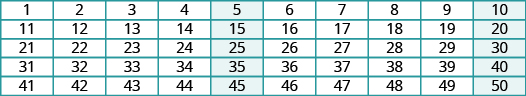

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows the counting numbers from \(1\) to \(50\). Multiples of \(2\) are highlighted. Do you notice a pattern?

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Multiples of 2 between 1 and 50

The last digit of each highlighted number in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) is either \(0\), \(2\), \(4\), \(6\), or \(8\). This is true for the product of \(2\) and any counting number. So, to tell if any number is a multiple of \(2\) look at the last digit. If it is \(0\), \(2\), \(4\), \(6\), or \(8\), then the number is a multiple of \(2\).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): multiples of \(2\)

Determine whether each of the following is a multiple of \(2\):

- \(489\)

- \(3,714\)

Solution

-

| Is 489 a multiple of 2? |

|

| Is the last digit 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8? |

No. |

| |

489 is not a multiple of 2. |

-

| Is 3,714 a multiple of 2? |

|

| Is the last digit 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8? |

Yes. |

| |

3,714 is a multiple of 2. |

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Determine whether each number is a multiple of \(2\):

- \(678\)

- \(21,493\)

- Answer a

-

yes

- Answer b

-

no

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Determine whether each number is a multiple of \(2\):

- \(979\)

- \(17,780\)

- Answer a

-

no

- Answer b

-

yes

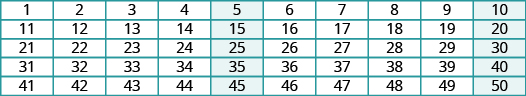

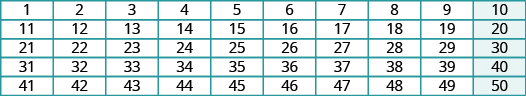

Now let’s look at multiples of \(5\). Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) highlights all of the multiples of \(5\) between \(1\) and \(50\). What do you notice about the multiples of \(5\)?

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Multiples of 5 between 1 and 50

All multiples of \(5\) end with either \(5\) or \(0\). Just like we identify multiples of \(2\) by looking at the last digit, we can identify multiples of \(5\) by looking at the last digit.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): multiples of \(5\)

Determine whether each of the following is a multiple of \(5\):

- \(579\)

- \(880\)

Solution

-

| Is 579 a multiple of 5? |

|

| Is the last digit 5 or 0? |

No. |

| |

579 is not a multiple of 5. |

-

| Is 880 a multiple of 5? |

|

| Is the last digit 5 or 0? |

Yes. |

| |

880 is not a multiple of 5. |

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Determine whether each number is a multiple of \(5\).

- \(675\)

- \(1,578\)

- Answer a

-

yes

- Answer b

-

no

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Determine whether each number is a multiple of \(5\).

- \(421\)

- \(2,690\)

- Answer a

-

no

- Answer b

-

yes

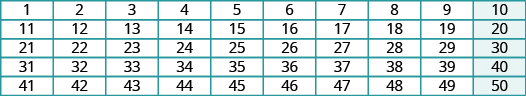

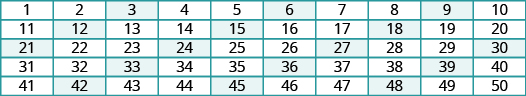

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) highlights the multiples of \(10\) between \(1\) and \(50\). All multiples of \(10\) all end with a zero.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Multiples of 10 between 1 and 50

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): multiples of \(10\)

Determine whether each of the following is a multiple of \(10\):

- \(425\)

- \(350\)

Solution

-

| Is 425 a multiple of 10? |

|

| Is the last digit zero? |

No. |

| |

425 is not a multiple of 10. |

-

| Is 350 a multiple of 10? |

|

| Is the last digit zero? |

Yes. |

| |

350 is a multiple of 10. |

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Determine whether each number is a multiple of \(10\):

- \(179\)

- \(3,540\)

- Answer a

-

no

- Answer b

-

yes

Exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Determine whether each number is a multiple of \(10\):

- \(110\)

- \(7,595\)

- Answer a

-

yes

- Answer b

-

no

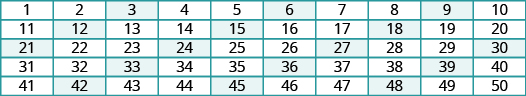

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) highlights multiples of \(3\). The pattern for multiples of \(3\) is not as obvious as the patterns for multiples of \(2\), \(5\), and \(10\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Multiples of 3 between 1 and 50

Unlike the other patterns we’ve examined so far, this pattern does not involve the last digit. The pattern for multiples of \(3\) is based on the sum of the digits. If the sum of the digits of a number is a multiple of \(3\), then the number itself is a multiple of \(3\). See Table \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Table \(\PageIndex{2}\)

| Multiple of 3 |

3 |

6 |

9 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

21 |

24 |

| Sum of digits |

3 |

6 |

9 |

1 + 2

3

|

1 + 5

6

|

1 + 8

9

|

2 + 1

3

|

2 + 4

6

|

Consider the number \(42\). The digits are \(4\) and \(2\), and their sum is \(4 + 2 = 6\). Since \(6\) is a multiple of \(3\), we know that \(42\) is also a multiple of \(3\).

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): multiples of \(3\)

Determine whether each of the given numbers is a multiple of \(3\):

- \(645\)

- \(10,519\)

Solution

- Is \(645\) a multiple of \(3\)?

| Find the sum of the digits. |

6 + 4 + 5 = 15 |

| Is 15 a multiple of 3? |

Yes. |

| If we're not sure, we could add its digits to find out. We can check it by dividing 645 by 3. |

645 ÷ 3 |

| The quotient is 215. |

3 • 215 = 645 |

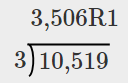

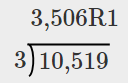

- Is \(10,519\) a multiple of \(3\)?

| Find the sum of the digits. |

1 + 0 + 5 + 1 + 9 = 16 |

| Is 15 a multiple of 3? |

No. |

| So 10,519 is not a multiple of 3 either.. |

645 ÷ 3 |

| We can check this by dividing by 10,519 by 3. |

|

When we divide \(10,519\) by \(3\), we do not get a counting number, so \(10,519\) is not the product of a counting number and \(3\). It is not a multiple of \(3\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Determine whether each number is a multiple of \(3\):

- \(954\)

- \(3,742\)

- Answer a

-

yes

- Answer b

-

no

Exercise \(\PageIndex{8}\)

Determine whether each number is a multiple of \(3\):

- \(643\)

- \(8,379\)

- Answer a

-

no

- Answer b

-

yes

Look back at the charts where you highlighted the multiples of \(2\), of \(5\), and of \(10\). Notice that the multiples of \(10\) are the numbers that are multiples of both \(2\) and \(5\). That is because \(10 = 2 • 5\). Likewise, since \(6 = 2 • 3\), the multiples of \(6\) are the numbers that are multiples of both \(2\) and \(3\).

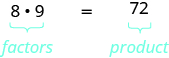

Find All the Factors of a Number

There are often several ways to talk about the same idea. So far, we’ve seen that if \(m\) is a multiple of \(n\), we can say that \(m\) is divisible by \(n\). We know that \(72\) is the product of \(8\) and \(9\), so we can say \(72\) is a multiple of \(8\) and \(72\) is a multiple of \(9\). We can also say \(72\) is divisible by \(8\) and by \(9\). Another way to talk about this is to say that \(8\) and \(9\) are factors of \(72\). When we write \(72 = 8 ⋅ 9\) we can say that we have factored \(72\).

Definition: Factors

If \(a • b = m\), then \(a\) and \(b\) are factors of \(m\), and \(m\) is the product of \(a\) and \(b\).

In algebra, it can be useful to determine all of the factors of a number. This is called factoring a number, and it can help us solve many kinds of problems.

For example, suppose a choreographer is planning a dance for a ballet recital. There are 24 dancers, and for a certain scene, the choreographer wants to arrange the dancers in groups of equal sizes on stage.

In how many ways can the dancers be put into groups of equal size? Answering this question is the same as identifying the factors of \(24\). Table \(\PageIndex{6}\) summarizes the different ways that the choreographer can arrange the dancers.

Table \(\PageIndex{6}\)

| Number of Groups |

Dancers per Group |

Total Dancers |

| 1 |

24 |

1 • 24 = 24 |

| 2 |

12 |

2 • 12= 24 |

| 3 |

8 |

3 • 8= 24 |

| 4 |

6 |

4 • 6= 24 |

| 6 |

4 |

6 • 4= 24 |

| 8 |

3 |

8 • 3= 24 |

| 12 |

2 |

12 • 2= 24 |

| 24 |

1 |

24 • 1= 24 |

What patterns do you see in Table \(\PageIndex{6}\)? Did you notice that the number of groups times the number of dancers per group is always \(24\)? This makes sense, since there are always \(24\) dancers.

You may notice another pattern if you look carefully at the first two columns. These two columns contain the exact same set of numbers—but in reverse order. They are mirrors of one another, and in fact, both columns list all of the factors of \(24\), which are:

\(1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24\)

We can find all the factors of any counting number by systematically dividing the number by each counting number, starting with \(1\). If the quotient is also a counting number, then the divisor and the quotient are factors of the number. We can stop when the quotient becomes smaller than the divisor.

HOW TO: FIND ALL THE FACTORS OF A COUNTING NUMBER.

Step 1. Divide the number by each of the counting numbers, in order, until the quotient is smaller than the divisor.

- If the quotient is a counting number, the divisor and quotient are a pair of factors.

- If the quotient is not a counting number, the divisor is not a factor.

Step 2. List all the factor pairs.

Step 3. Write all the factors in order from smallest to largest.

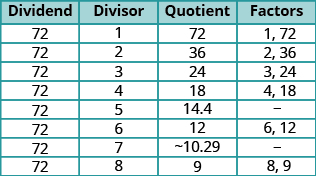

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\): factors

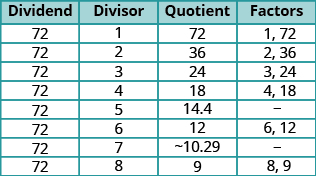

Find all the factors of \(72\).

Solution

Divide \(72\) by each of the counting numbers starting with \(1\). If the quotient is a whole number, the divisor and quotient are a pair of factors.

The next line would have a divisor of \(9\) and a quotient of \(8\). The quotient would be smaller than the divisor, so we stop. If we continued, we would end up only listing the same factors again in reverse order. Listing all the factors from smallest to greatest, we have \(1\), \(2\), \(3\), \(4\), \(6\), \(8\), \(9\), \(12\), \(18\), \(24\), \(36\), and \(72\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{13}\)

Find all the factors of the given number: \(96\)

- Answer

-

\(1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 48, 96\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{14}\)

Find all the factors of the given number: \(80\)

- Answer

-

\(1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 10, 16, 20, 40, 80\)