5.1: Solve Systems of Equations by Graphing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 61403

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Determine whether an ordered pair is a solution of a system of equations

- Solve a system of linear equations by graphing

- Determine the number of solutions of linear system

- Solve applications of systems of equations by graphing

Note

Before you get started, take this readiness quiz.

- For the equation \(y=\frac{2}{3}x−4\)

ⓐ is (6,0) a solution? ⓑ is (−3,−2) a solution?

If you missed this problem, review Example 2.1.1. - Find the slope and y-intercept of the line 3x−y=12.

If you missed this problem, review Example 4.5.7. - Find the x- and y-intercepts of the line 2x−3y=12.

If you missed this problem, review Example 4.3.7.

Determine Whether an Ordered Pair is a Solution of a System of Equations

In the section on Solving Linear Equations and Inequalities we learned how to solve linear equations with one variable. Remember that the solution of an equation is a value of the variable that makes a true statement when substituted into the equation. Now we will work with systems of linear equations, two or more linear equations grouped together.

Definition: SYSTEM OF LINEAR EQUATIONS

When two or more linear equations are grouped together, they form a system of linear equations.

We will focus our work here on systems of two linear equations in two unknowns. Later, you may solve larger systems of equations.

An example of a system of two linear equations is shown below. We use a brace to show the two equations are grouped together to form a system of equations.

\[\begin{cases}{2 x+y=7} \\ {x-2 y=6}\end{cases}\]

A linear equation in two variables, like 2x + y = 7, has an infinite number of solutions. Its graph is a line. Remember, every point on the line is a solution to the equation and every solution to the equation is a point on the line.

To solve a system of two linear equations, we want to find the values of the variables that are solutions to both equations. In other words, we are looking for the ordered pairs (x, y) that make both equations true. These are called the solutions to a system of equations.

Definition: SolutionS OF A SYSTEM OF EQUATIONS

Solutions of a system of equations are the values of the variables that make all the equations true. A solution of a system of two linear equations is represented by an ordered pair (x, y).

To determine if an ordered pair is a solution to a system of two equations, we substitute the values of the variables into each equation. If the ordered pair makes both equations true, it is a solution to the system.

Let’s consider the system below:

\[\begin{cases}{3x−y=7} \\ {x−2y=4}\end{cases}\]

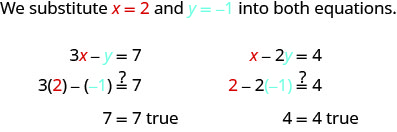

Is the ordered pair (2,−1) a solution?

The ordered pair (2, −1) made both equations true. Therefore (2, −1) is a solution to this system.

Let’s try another ordered pair. Is the ordered pair (3, 2) a solution?

The ordered pair (3, 2) made one equation true, but it made the other equation false. Since it is not a solution to both equations, it is not a solution to this system.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

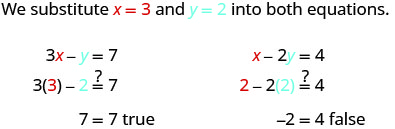

Determine whether the ordered pair is a solution to the system: \(\begin{cases}{x−y=−1} \\ {2x−y=−5}\end{cases}\)

- (−2,−1)

- (−4,−3)

Solution

1.

\(\begin{cases}{x−y=−1} \\ {2x−y=−5}\end{cases}\)

\( \text{We substitute } {\color{red}{x=-2}} \text{ and } {\color{Cerulean}{y=-1}} \text{ into both equations} \)

\begin{align*}

x-y&=1 & 2x-y &=-5 \\

{\color{red}{-2}}-({\color{Cerulean}{-1}})&=-1 & 2({\color{red}{-2}})-({\color{Cerulean}{-1}})&\overset{?}{=}-5 \\

-1&=-1 \, ✓ & -3&=-5 \, ✗

\end{align*}

(−2, −1) does not make both equations true. (−2, −1) is not a solution.

2.

(−4, −3) makes both equations true. (−4, −3) is a solution.

Try It \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Determine whether the ordered pair is a solution to the system: \(\begin{cases}{3x+y=0} \\ {x+2y=−5}\end{cases}\)

- (1,−3)

- (0,0)

- Answer

-

- yes

- no

Try It \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Determine whether the ordered pair is a solution to the system: \(\begin{cases}{x−3y=−8} \\ {−3x−y=4}\end{cases}\)

- (2,−2)

- (−2,2)

- Answer

-

- no

- yes

Solve a System of Linear Equations by Graphing

In this chapter we will use three methods to solve a system of linear equations. The first method we’ll use is graphing. The graph of a linear equation is a line. Each point on the line is a solution to the equation. For a system of two equations, we will graph two lines. Then we can see all the points that are solutions to each equation. And, by finding what the lines have in common, we’ll find the solution to the system.

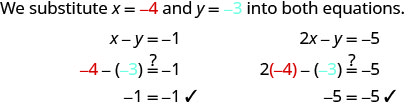

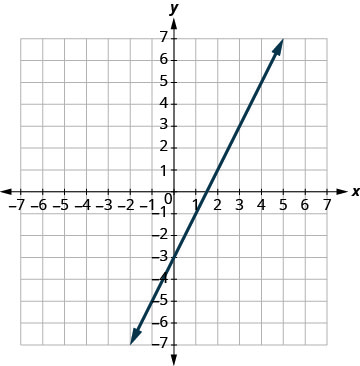

Most linear equations in one variable have one solution, but we saw that some equations, called contradictions, have no solutions and for other equations, called identities, all numbers are solutions. Similarly, when we solve a system of two linear equations represented by a graph of two lines in the same plane, there are three possible cases, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\):

For the first example of solving a system of linear equations in this section and in the next two sections, we will solve the same system of two linear equations. But we’ll use a different method in each section. After seeing the third method, you’ll decide which method was the most convenient way to solve this system.

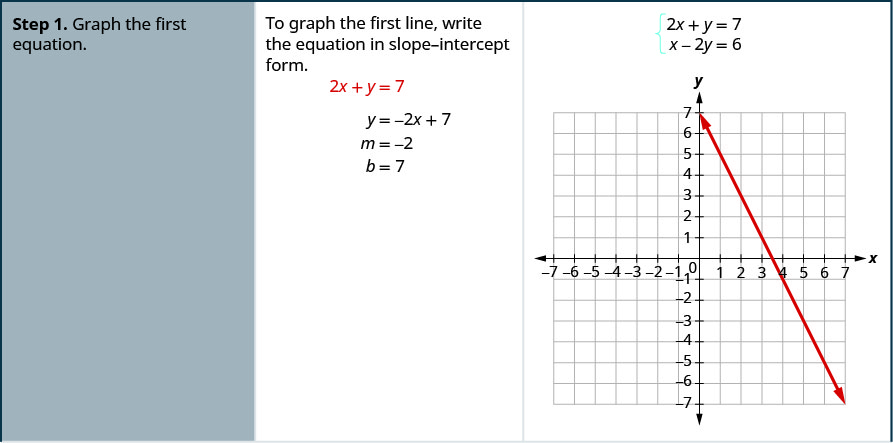

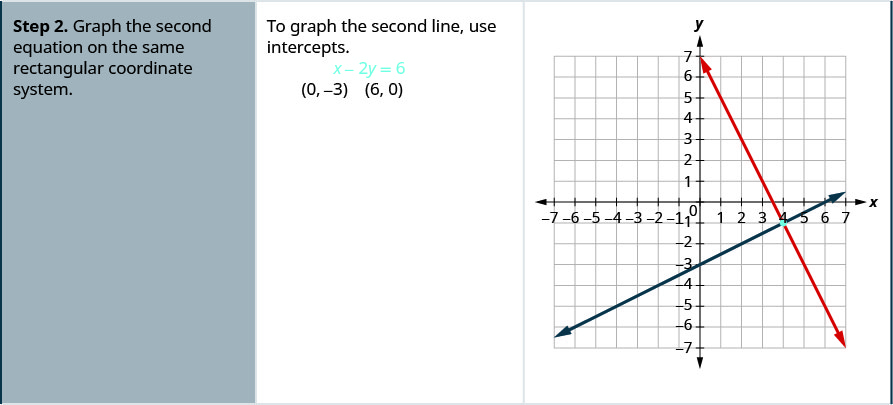

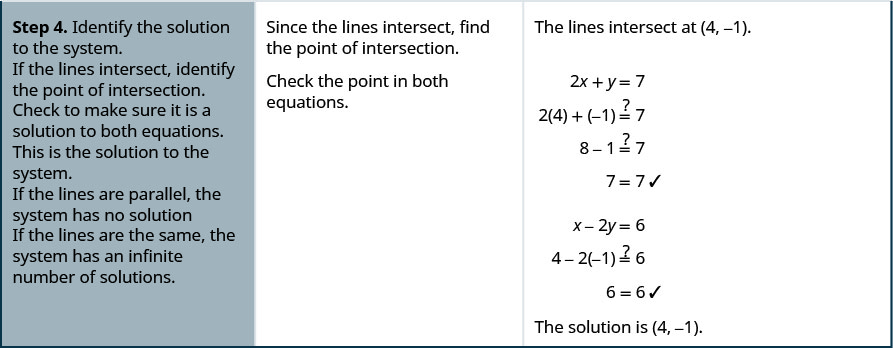

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): How to Solve a System of Linear Equations by Graphing

Solve the system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{2x+y=7} \\ {x−2y=6}\end{cases}\)

Solution

Try It \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{x−3y=−3} \\ {x+y=5}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(3,2)

Try It \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{−x+y=1} \\ {3x+2y=12}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(2,3)

The steps to use to solve a system of linear equations by graphing are shown below.

TO SOLVE A SYSTEM OF LINEAR EQUATIONS BY GRAPHING.

- Graph the first equation.

- Graph the second equation on the same rectangular coordinate system.

- Determine whether the lines intersect, are parallel, or are the same line.

- Identify the solution to the system.

- If the lines intersect, identify the point of intersection. Check to make sure it is a solution to both equations. This is the solution to the system.

- If the lines are parallel, the system has no solution.

- If the lines are the same, the system has an infinite number of solutions.

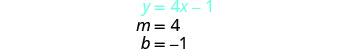

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Solve the system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=2x+1} \\ {y=4x−1}\end{cases}\)

Solution

Both of the equations in this system are in slope-intercept form, so we will use their slopes and y-intercepts to graph them. \(\begin{cases}{y=2x+1} \\ {y=4x−1}\end{cases}\)

| Find the slope and y-intercept of the first equation. |

|

| Find the slope and y-intercept of the first equation. |

|

| Graph the two lines. | |

| Determine the point of intersection. | The lines intersect at (1, 3). |

|

|

| Check the solution in both equations. | \(\begin{array}{l}{y=2 x+1} & {y = 4x - 1}\\{3\stackrel{?}{=}2 \cdot 1+1} &{3\stackrel{?}{=}4 \cdot 1-1} \\ {3=3 \checkmark}&{3=3 \checkmark} \end{array}\) |

| The solution is (1, 3). |

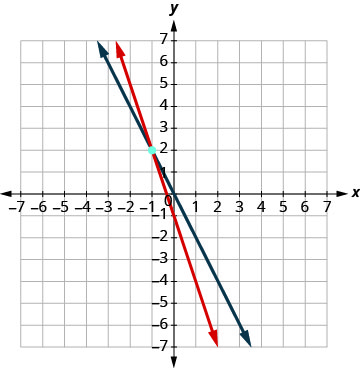

Try It \(\PageIndex{8}\)

Solve the system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=2x+2} \\ {y=-x−4}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(−2,−2)

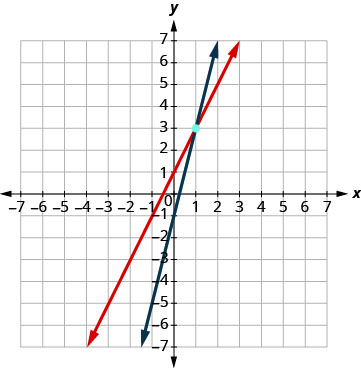

Try It \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Solve the system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=3x+3} \\ {y=-x+7}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(1,6)

Both equations in Example \(\PageIndex{7}\) were given in slope–intercept form. This made it easy for us to quickly graph the lines. In the next example, we’ll first re-write the equations into slope–intercept form.

Example \(\PageIndex{10}\)

Solve the system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{3x+y=−1} \\ {2x+y=0}\end{cases}\)

Solution

We’ll solve both of these equations for \(y\) so that we can easily graph them using their slopes and y-intercepts. \(\begin{cases}{3x+y=−1} \\ {2x+y=0}\end{cases}\)

| Solve the first equation for y. Find the slope and y-intercept. Solve the second equation for y. Find the slope and y-intercept. |

\(\begin{aligned} 3 x+y &=-1 \\ y &=-3 x-1 \\ m &=-3 \\ b &=-1 \\ 2 x+y &=0 \\ y &=-2 x \\ b &=0 \end{aligned}\) |

| Graph the lines. |  |

| Determine the point of intersection. | The lines intersect at (−1, 2). |

| Check the solution in both equations. | \(\begin{array}{rllrll}{3x+y}&{=}&{-1} & {2x +y}&{=}&{0}\\{3(-1)+ 2}&{\stackrel{?}{=}}&{-1} &{2(-1)+2}&{\stackrel{?}{=}}&{0} \\ {-1}&{=}&{-1 \checkmark}&{0}&{=}&{0 \checkmark} \end{array}\) |

| The solution is (−1, 2). |

Try It \(\PageIndex{11}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{−x+y=1} \\ {2x+y=10}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(3,4)

Try It \(\PageIndex{12}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{ 2x+y=6} \\ {x+y=1}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(5,−4)

Usually when equations are given in standard form, the most convenient way to graph them is by using the intercepts. We’ll do this in Example \(\PageIndex{13}\).

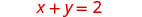

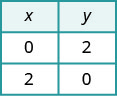

Example \(\PageIndex{13}\)

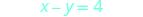

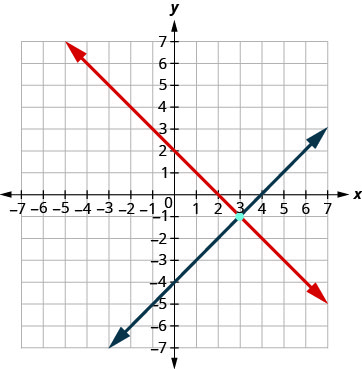

Solve the system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{x+y=2} \\ {x−y=4}\end{cases}\)

Solution

We will find the x- and y-intercepts of both equations and use them to graph the lines.

|

||

| To find the intercepts, let x = 0 and solve for y, then let y = 0 and solve for x. |

\(\begin{aligned} x+y &=2 \quad x+y=2 \\ 0+y &=2 \quad x+0=2 \\ y &=2 \quad x=2 \end{aligned}\) |  |

|

||

| To find the intercepts, let x = 0 then let y = 0. |

\begin{array}{rlr}{x-y} & {=4} &{x-y} &{= 4} \\ {0-y} & {=4} & {x-0} & {=4} \\{-y} & {=4} & {x}&{=4}\\ {y} & {=-4}\end{array} |  |

| Graph the line. |  |

|

| Determine the point of intersection. | The lines intersect at (3, −1). | |

| Check the solution in both equations. |

\(\begin{array}{rllrll}{x+y}&{=}&{2} & {x-y}&{=}&{4}\\{3+(-1)}&{\stackrel{?}{=}}&{2} &{3 - (-1)}&{\stackrel{?}{=}}&{4} \\ {2}&{=}&{2 \checkmark}&{4}&{=}&{4 \checkmark} \end{array}\) The solution is (3, −1). |

Try It \(\PageIndex{14}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{x+y=6} \\ {x−y=2}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(4,2)

Try It \(\PageIndex{15}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{x+y=2} \\ {x−y=8}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(5,−3)

Do you remember how to graph a linear equation with just one variable? It will be either a vertical or a horizontal line.

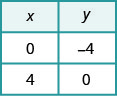

Example \(\PageIndex{16}\)

Solve the system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=6} \\ {2x+3y=12}\end{cases}\)

Solution

|

|

| We know the first equation represents a horizontal line whose y-intercept is 6. |

|

| The second equation is most conveniently graphed using intercepts. |

|

| To find the intercepts, let x = 0 and then y = 0. |  |

| Graph the lines. |  |

| Determine the point of intersection. | The lines intersect at (−3, 6). |

| Check the solution to both equations. | \(\begin{array}{rllrll}{y}&{=}&{6} & {2x+3y}&{=}&{12}\\{6}&{\stackrel{?}{=}}&{6} &{2(-3) + 3(6)}&{\stackrel{?}{=}}&{12} \\ {6}&{=}&{6 \checkmark} &{-6+18}&{\stackrel{?}{=}}&{12} \\ {}&{}&{}&{12}&{=}&{12 \checkmark} \end{array}\) |

| The solution is (−3, 6). |

Try It \(\PageIndex{17}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=−1} \\ {x+3y=6}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(9,−1)

Try It \(\PageIndex{18}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{x=4} \\ {3x−2y=24}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

(4,−6)

In all the systems of linear equations so far, the lines intersected and the solution was one point. In the next two examples, we’ll look at a system of equations that has no solution and at a system of equations that has an infinite number of solutions.

Example \(\PageIndex{19}\)

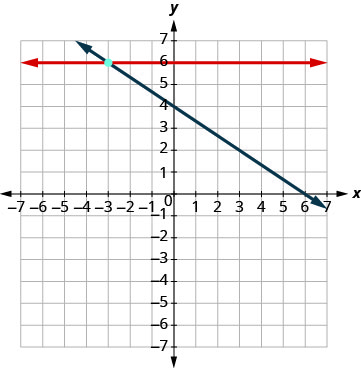

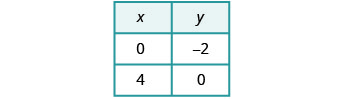

Solve the system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=\frac{1}{2}x−3} \\ {x−2y=4}\end{cases}\)

Solution

|

|

| To graph the first equation, we will use its slope and y-intercept. |

|

|

|

|

|

| To graph the second equation, we will use the intercepts. |

|

|

|

| Graph the lines. |  |

| Determine the point of intersection. | The lines are parallel. |

| Since no point is on both lines, there is no ordered pair that makes both equations true. There is no solution to this system. |

Try It \(\PageIndex{20}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=-\frac{1}{4}x+2} \\ {x+4y=-8}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

no solution

Try It \(\PageIndex{21}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=3x−1} \\ {6x−2y=6}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

no solution

Example \(\PageIndex{22}\)

Solve the system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=2x−3} \\ {−6x+3y=−9}\end{cases}\)

Solution

|

|

| Find the slope and y-intercept of the first equation. |

|

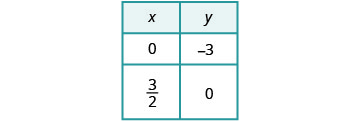

| Find the intercepts of the second equation. |  |

|

|

| Graph the lines. |  |

| Determine the point of intersection. | The lines are the same! |

| Since every point on the line makes both equations true, there are infinitely many ordered pairs that make both equations true. |

|

| There are infinitely many solutions to this system. |

Try It \(\PageIndex{23}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=−3x−6} \\ {6x+2y=−12}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

infinitely many solutions

Try It \(\PageIndex{24}\)

Solve each system by graphing: \(\begin{cases}{y=\frac{1}{2}x−4} \\ {2x−4y=16}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

infinitely many solutions

If you write the second equation in Example \(\PageIndex{22}\) in slope-intercept form, you may recognize that the equations have the same slope and same y-intercept.

When we graphed the second line in the last example, we drew it right over the first line. We say the two lines are coincident. Coincident lines have the same slope and same y-intercept.

COINCIDENT LINES

Coincident lines have the same slope and same y-intercept.

Determine the Number of Solutions of a Linear System

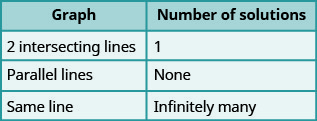

There will be times when we will want to know how many solutions there will be to a system of linear equations, but we might not actually have to find the solution. It will be helpful to determine this without graphing.

We have seen that two lines in the same plane must either intersect or are parallel. The systems of equations in Example \(\PageIndex{4}\) through Example \(\PageIndex{18}\) all had two intersecting lines. Each system had one solution.

A system with parallel lines, like Example \(\PageIndex{19}\), has no solution. What happened in Example \(\PageIndex{22}\)? The equations have coincident lines, and so the system had infinitely many solutions.

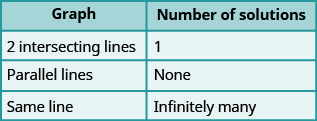

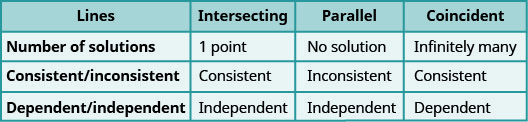

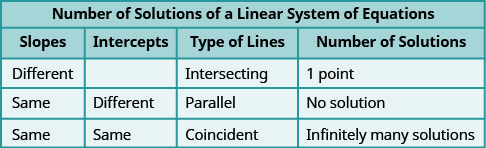

We’ll organize these results in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) below:

Parallel lines have the same slope but different y-intercepts. So, if we write both equations in a system of linear equations in slope–intercept form, we can see how many solutions there will be without graphing! Look at the system we solved in Example \(\PageIndex{19}\).

\(\begin{array} {cc} & \begin{cases}{y=\frac{1}{2}x−3} \\ {x−2y=4}\end{cases}\\ \text{The first line is in slope–intercept form.} &\text { If we solve the second equation for } y, \text { we get } \\ &x-2 y =4 \\ y = \frac{1}{2}x -3& x-2 y =-x+4 \\ &y =\frac{1}{2} x-2 \\ m=\frac{1}{2}, b=-3&m=\frac{1}{2}, b=-2 \end{array}\)

The two lines have the same slope but different y-intercepts. They are parallel lines.

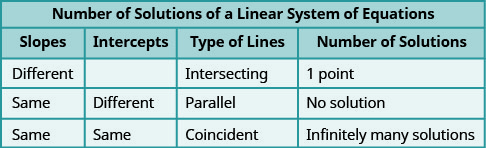

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows how to determine the number of solutions of a linear system by looking at the slopes and intercepts.

Let’s take one more look at our equations in Example \(\PageIndex{19}\) that gave us parallel lines.

\[\begin{cases}{y=\frac{1}{2}x−3} \\ {x−2y=4}\end{cases}\]

When both lines were in slope-intercept form we had:

\[y=\frac{1}{2} x-3 \quad y=\frac{1}{2} x-2\]

Do you recognize that it is impossible to have a single ordered pair (x,y) that is a solution to both of those equations?

We call a system of equations like this an inconsistent system. It has no solution.

A system of equations that has at least one solution is called a consistent system.

CONSISTENT AND INCONSISTENT SYSTEMS

A consistent system of equations is a system of equations with at least one solution.

An inconsistent system of equations is a system of equations with no solution.

We also categorize the equations in a system of equations by calling the equations independent or dependent. If two equations are independent equations, they each have their own set of solutions. Intersecting lines and parallel lines are independent.

If two equations are dependent, all the solutions of one equation are also solutions of the other equation. When we graph two dependent equations, we get coincident lines.

INDEPENDENT AND DEPENDENT EQUATIONS

Two equations are independent if they have different solutions.

Two equations are dependent if all the solutions of one equation are also solutions of the other equation.

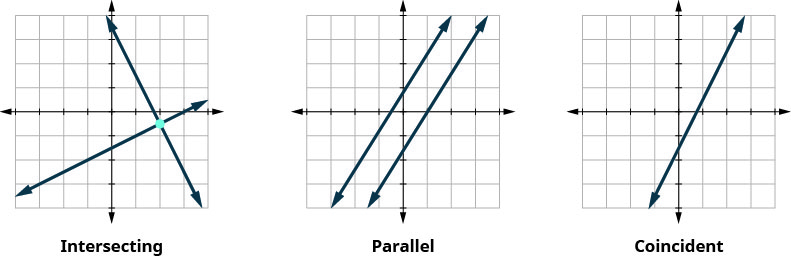

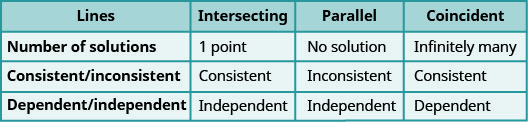

Let’s sum this up by looking at the graphs of the three types of systems. See Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) and Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{25}\)

Without graphing, determine the number of solutions and then classify the system of equations: \(\begin{cases}{y=3x−1} \\ {6x−2y=12}\end{cases}\)

Solution

\(\begin{array}{lrrl} \text{We will compare the slopes and intercepts} & \begin{cases}{y=3x−1} \\ {6x−2y=12}\end{cases} \\ \text{of the two lines.} \\ \text{The first equation is already in} \\ \text{slope-intercept form.} \\ & {y = 3x - 1}\\ \text{Write the second equation in} \text{slope–intercept form.} \\

&& 6x-2y =&12 \\

&& -2y =& -6x - 12 \\

&&\frac{-2y}{-2}=& \frac{-6x + 12}{-2}\\

&&y=&3x-6\\\\ \text{Find the slope and intercept of each line.} & y = 3x-1 & y=3x-6 \\ &m = 3 & m = 3 \\&b=-1 &b=-6 \\ \text{Since the slopes are the same and y-intercepts} \\ \text{are different, the lines are parallel.}\end{array}\)

A system of equations whose graphs are parallel lines has no solution and is inconsistent and independent.

Try It \(\PageIndex{26}\)

Without graphing, determine the number of solutions and then classify the system of equations.

\(\begin{cases}{y=−2x−4} \\ {4x+2y=9}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

no solution, inconsistent, independent

Try It \(\PageIndex{27}\)

Without graphing, determine the number of solutions and then classify the system of equations.

\(\begin{cases}{y=\frac{1}{3}x−5} \\ {x-3y=6}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

no solution, inconsistent, independent

Example \(\PageIndex{28}\)

Without graphing, determine the number of solutions and then classify the system of equations: \(\begin{cases}{2x+y=−3} \\ {x−5y=5}\end{cases}\)

Solution

\(\begin{array}{lrrlrl} \text{We will compare the slopes and intercepts} & \begin{cases}{2x+y=-3} \\ {x−5y=5}\end{cases} \\ \text{of the two lines.} \\ \text{Write the second equation in} \\ \text{slope–intercept form.} \\ &2x+y&=&-3 & x−5y&=&5\\ & y &=& -2x -3 & -5y &=&-x+5 \\ &&&&\frac{-5y}{-5} &=& \frac{-x + 5}{-5}\\ &&&&y&=&\frac{1}{5}x-1\\\\ \text{Find the slope and intercept of each line.} & y &=& -2x-3 & y&=&\frac{1}{5}x-1 \\ &m &=& -2 & m &=& \frac{1}{5} \\&b&=&-3 &b&=&-1 \\ \text{Since the slopes are different, the lines intersect.}\end{array}\)

A system of equations whose graphs are intersect has 1 solution and is consistent and independent.

Try It \(\PageIndex{29}\)

Without graphing, determine the number of solutions and then classify the system of equations.

\(\begin{cases}{3x+2y=2} \\ {2x+y=1}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

one solution, consistent, independent

Try It \(\PageIndex{30}\)

Without graphing, determine the number of solutions and then classify the system of equations.

\(\begin{cases}{x+4y=12} \\ {−x+y=3}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

one solution, consistent, independent

Example \(\PageIndex{31}\)

Without graphing, determine the number of solutions and then classify the system of equations. \(\begin{cases}{3x−2y=4} \\ {y=\frac{3}{2}x−2}\end{cases}\)

Solution

\(\begin{array}{lrrlrl} \text{We will compare the slopes and intercepts of the two lines.}& \begin{cases}{3x−2y} &=&{4} \\ {y}&=&{\frac{3}{2}x−2}\end{cases} \\ \text{Write the second equation in} \\ \text{slope–intercept form.} \\ &3x-2y&=&4 \\ & -2y &=& -3x +4 \\ &\frac{-2y}{-2} &=& \frac{-3x + 4}{-2}\\ &y&=&\frac{3}{2}x-2\\\\ \text{Find the slope and intercept of each line.} &y&=&\frac{3}{2}x-2\\ \text{Since the equations are the same, they have the same slope} \\ \text{and same y-intercept and so the lines are coincident.}\end{array}\)

A system of equations whose graphs are coincident lines has infinitely many solutions and is consistent and dependent.

Try It \(\PageIndex{32}\)

Without graphing, determine the number of solutions and then classify the system of equations.

\(\begin{cases}{4x−5y=20} \\ {y=\frac{4}{5}x−4}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

infinitely many solutions, consistent, dependent

Try It \(\PageIndex{33}\)

Without graphing, determine the number of solutions and then classify the system of equations.

\(\begin{cases}{ −2x−4y=8} \\ {y=−\frac{1}{2}x−2}\end{cases}\)

- Answer

-

infinitely many solutions, consistent, dependent

Solve Applications of Systems of Equations by Graphing

We will use the same problem solving strategy we used in Math Models to set up and solve applications of systems of linear equations. We’ll modify the strategy slightly here to make it appropriate for systems of equations.

USE A PROBLEM SOLVING STRATEGY FOR SYSTEMS OF LINEAR EQUATIONS.

- Read the problem. Make sure all the words and ideas are understood.

- Identify what we are looking for.

- Name what we are looking for. Choose variables to represent those quantities.

- Translate into a system of equations.

- Solve the system of equations using good algebra techniques.

- Check the answer in the problem and make sure it makes sense.

- Answer the question with a complete sentence.

Step 5 is where we will use the method introduced in this section. We will graph the equations and find the solution.

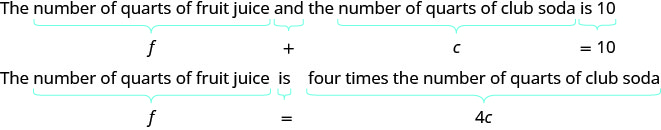

Example \(\PageIndex{34}\)

Sondra is making 10 quarts of punch from fruit juice and club soda. The number of quarts of fruit juice is 4 times the number of quarts of club soda. How many quarts of fruit juice and how many quarts of club soda does Sondra need?

Solution

Step 1. Read the problem.

Step 2. Identify what we are looking for.

We are looking for the number of quarts of fruit juice and the number of quarts of club soda that Sondra will need.

Step 3. Name what we are looking for. Choose variables to represent those quantities.

Let f= number of quarts of fruit juice.

c= number of quarts of club soda

Step 4. Translate into a system of equations.

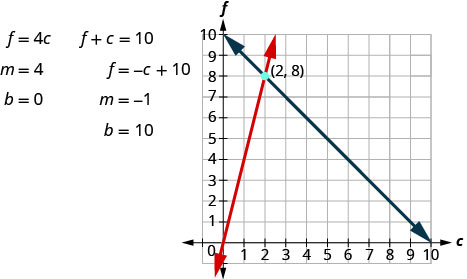

We now have the system. \(\begin{cases}{ f+c=10} \\ {f=4c}\end{cases}\)

Step 5. Solve the system of equations using good algebra techniques.

The point of intersection (2, 8) is the solution. This means Sondra needs 2 quarts of club soda and 8 quarts of fruit juice.

Step 6. Check the answer in the problem and make sure it makes sense.

Does this make sense in the problem?

Yes, the number of quarts of fruit juice, 8 is 4 times the number of quarts of club soda, 2.

Yes, 10 quarts of punch is 8 quarts of fruit juice plus 2 quarts of club soda.

Step 7. Answer the question with a complete sentence.

Sondra needs 8 quarts of fruit juice and 2 quarts of soda.

Try It \(\PageIndex{35}\)

Manny is making 12 quarts of orange juice from concentrate and water. The number of quarts of water is 3 times the number of quarts of concentrate. How many quarts of concentrate and how many quarts of water does Manny need?

- Answer

-

Manny needs 3 quarts juice concentrate and 9 quarts water.

Try It \(\PageIndex{36}\)

Alisha is making an 18 ounce coffee beverage that is made from brewed coffee and milk. The number of ounces of brewed coffee is 5 times greater than the number of ounces of milk. How many ounces of coffee and how many ounces of milk does Alisha need?

- Answer

-

Alisha needs 15 ounces of coffee and 3 ounces of milk.

Note

Access these online resources for additional instruction and practice with solving systems of equations by graphing.

Key Concepts

- To solve a system of linear equations by graphing

- Graph the first equation.

- Graph the second equation on the same rectangular coordinate system.

- Determine whether the lines intersect, are parallel, or are the same line.

- Identify the solution to the system.

If the lines intersect, identify the point of intersection. Check to make sure it is a solution to both equations. This is the solution to the system.

If the lines are parallel, the system has no solution.

If the lines are the same, the system has an infinite number of solutions. - Check the solution in both equations.

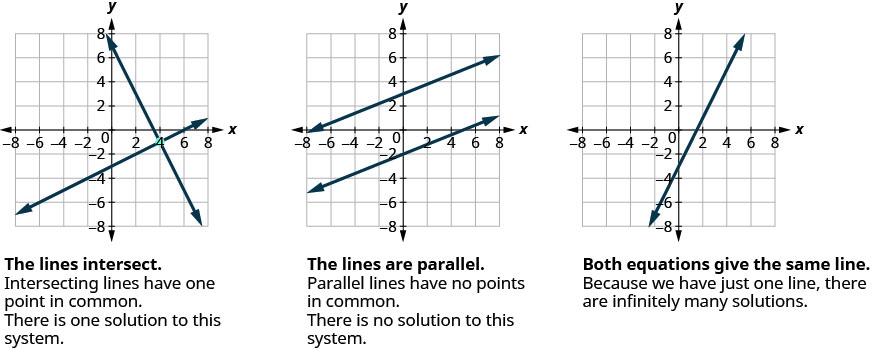

- Determine the number of solutions from the graph of a linear system

- Determine the number of solutions of a linear system by looking at the slopes and intercepts

- Determine the number of solutions and how to classify a system of equations

- Problem Solving Strategy for Systems of Linear Equations

- Read the problem. Make sure all the words and ideas are understood.

- Identify what we are looking for.

- Name what we are looking for. Choose variables to represent those quantities.

- Translate into a system of equations.

- Solve the system of equations using good algebra techniques.

- Check the answer in the problem and make sure it makes sense.

- Answer the question with a complete sentence.

Glossary

- coincident lines

- Coincident lines are lines that have the same slope and same y-intercept.

- consistent system

- A consistent system of equations is a system of equations with at least one solution.

- dependent equations

- Two equations are dependent if all the solutions of one equation are also solutions of the other equation.

- inconsistent system

- An inconsistent system of equations is a system of equations with no solution.

- independent equations

- Two equations are independent if they have different solutions.

- solutions of a system of equations

- Solutions of a system of equations are the values of the variables that make all the equations true. A solution of a system of two linear equations is represented by an ordered pair (x, y).

- system of linear equations

- When two or more linear equations are grouped together, they form a system of linear equations.