5.2: Definition of Functions

- Page ID

- 25160

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Definition: Function

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be nonempty sets. A function from \(A\) to \(B\) is a rule that assigns to every element of \(A\) a unique element in \(B\). We call \(A\) the domain, and \(B\) the codomain, of the function. If the function is called \(f\), we write \(f :A \to B\). Given \(x\in A\), its associated element in \(B\) is called its image under \(f\). In other words, a function is a relation from \(A\) to \(B\) with the condition that for every element in the domain, there exists a unique image in the codomain (this is really two conditions: existence of an image and uniqueness of an image). We denote it \(f(x)\), which is pronounced as “ \(f\) of \(x\).”

A function is sometimes called a map or mapping. Hence, we sometimes say \(f\) maps \(x\) to its image \(f(x)\).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\label{eg:defnfcn-01}\)

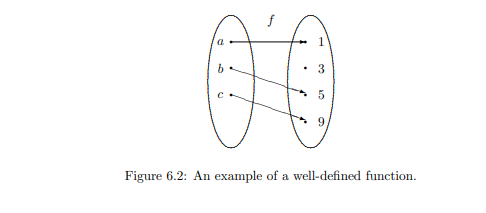

The function \(f:\{a,b,c\} \) to \(\{1,3,5,9\}\) is defined according to the rule \[f(a)=1, \qquad f(b)=5, \qquad\mbox{and}\qquad f(c) = 9.\] It is a well-defined function. The rule of assignment can be summarized in a table: \[\begin{array}{|c||c|c|c|} \hline x & a & b & c \\ \hline f(x)& 1 & 5 & 9 \\ \hline \end{array}\] We can also describe the assignment rule pictorially with an arrow diagram, as shown in Figure 6.2.

The two key requirements of a function are

- every element in the domain has an image under \(f\), and

- the image is unique.

You may want to remember that every element in \(A\) has exactly one “partner” in \(B\).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\label{eg:defnfcn-02}\)

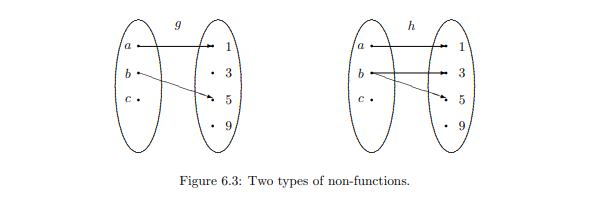

Figure 6.3 depicts two examples of non-functions. In the one on the left, one of the elements in the domain has no image associated with it; thus lacking existence of an image. In the one on the right, one of the elements in the domain has two images assigned to it; thus lacking uniqueness of an image. Both are not functions.

hands-on exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\label{he:defnfcn-01}\)

Do these rules \[\begin{array}{|c||c|c|c|} \hline x & a & b & c \\ \hline f(x)& 5 & 3 & 3 \\ \hline \end{array} \hskip0.75in \begin{array}{|c||c|c|} \hline x & b & c \\ \hline g(x)& 9 & 5 \\ \hline \end{array} \hskip0.75in \begin{array}{|c||c|c|c|c|} \hline x & a & b & b & c \\ \hline h(x)& 1 & 5 & 3 & 9 \\ \hline \end{array}\] produce functions from \(\{a,b,c\}\) to \(\{1,3,5,9\}\)? Explain.

hands-on exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\label{he:defnfcn-02}\)

Does the definition \[r(x) = \cases{ x & if today is Monday, \cr 2x & if today is not Monday \cr}\] produce a function from \(\mathbb{R}\) to \(\mathbb{R}\)? Explain.

hands-on exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\label{he:defnfcn-03}\)

Does the definition \[s(x) = \cases{ 5 & if $x<2$, \cr 7 & if $x>3$, \cr}\] produce a function from \(\mathbb{R}\) to \(\mathbb{R}\)? Explain.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\label{eg:defnfcn-03}\)

The function \(f:{[0,\infty)}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) is defined by \[f(x) = \sqrt{x}.\] Also the function \({g}:{[2,\infty)}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) is defined as \[g(x) = \sqrt{x-2}.\] Can you explain why the domain of \(g\) is \([2,\infty)\)?

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\label{eg:defnfcn-04}\)

Let \(A\) denote the set of students taking Discrete Mathematics, and \(G=\{A,B,C,D,F\}\), and \(\ell(x)\) is the final grade of student \(x\) in Discrete Mathematics. Every student should receive a final grade, and the instructor has to report one and only one final grade for each student. \(\ell:A \to G.\) This is precisely what we call a function.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\label{eg:defnfcn-05}\)

The function \({n}:{\mathscr{P}(\{a,b,c,d\})}\to{\mathbb{Z}}\) is defined as \(n(S)=|S|\). It evaluates the cardinality of a subset of \(\{a,b,c,d\}\). For example, \[n\big(\{a,c\}\big) = n\big(\{b,d\}\big) = 2.\] Note that \(n(\emptyset)=0\).

hands-on exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\label{he:defnfcn-04}\)

Consider Example 5.2.5. What other subsets \(S\) of \(\{a,b,c,d\}\) also yield \(n(S)=2\)? What are the smallest and the largest images the function \(n\) can produce?

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\label{eg:defnfcn-06}\)

Consider a function \({f}:{\mathbb{Z}_7}\to{\mathbb{Z}_5}\). The domain and the codomain are,

\[\mathbb{Z}_7 = \{0,1,2,3,4,5,6\}, \qquad\mbox{and}\qquad \mathbb{Z}_5 = \{0,1,2,3,4\},\]

respectively. Not only are their elements different, their binary operations are different too. In the domain \(\mathbb{Z}_7\), the arithmetic is performed modulo 7, but the arithmetic in the codomain \(\mathbb{Z}_5\) is done modulo 5. So we need to be careful in describing the rule of assignment if a computation is involved. We could say, for example,

\[f(x) = z, \quad\mbox{where } z \equiv 3x \pmod{5}.\]

Consequently, starting with any element \(x\) in \(\mathbb{Z}_7\), we consider \(x\) as an ordinary integer, multiply by 3, and reduce the answer modulo 5 to obtain the image \(f(x)\). For brevity, we shall write

\[f(x) \equiv 3x \pmod{5}.\]

We summarize the images in the following table:

\[\begin{array}{|c||*{7}{c|}} \hline n & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 \\ \hline f(n) & 0 & 3 & 1 & 4 & 2 & 0 & 3 \\ \hline \end{array}\]

Take note that the images start repeating after \(f(4)=2\).

hands-on exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\label{he:defnfcn-05}\)

Tabulate the images of \({g}:{\mathbb{Z}_{10}}\to{\mathbb{Z}_5}\) defined by \[g(x) \equiv 3x \pmod{5}.\]

Definition: A Function as a Set of Ordered Pairs

A function \({f}:{A}\to{B}\) can be written as a set of ordered pairs \((x,y)\) from \(A\times B\) such that \(y=f(x)\).

A function is, by definition, a set of ordered pairs, with certain restrictions.

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\label{eg:defnfcn-07}\)

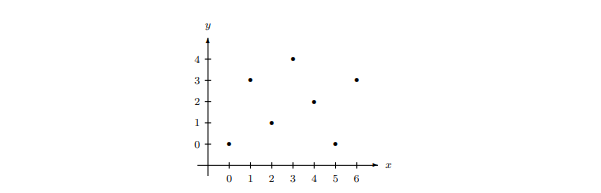

The function \(f\) in Example 5.26 can be written as the set of ordered pairs \[\{(0,0), (1,3), (2,1), (3,4), (4,2), (5,0), (6,3)\}.\] If one insists, we could display the graph of a function using an \(xy\)-plane that resembles the usual Cartesian plane. Keep in mind: the elements \(x\) and \(y\) come from \(A\) and \(B\), respectively. We can “plot” the graph for \(f\) in Example 5.26 as shown below.

Besides using a graphical representation, we can also use a \((0,1)\)-matrix. A \((0,1)\)-matrix is a matrix whose entries are 0 and 1. For the function \(f\), we use a \(7\times5\) matrix, whose rows and columns correspond to the elements of \(A\) and \(B\), respectively, and put one in the \((i,j)\)th entry if \(j=f(i)\), and zero otherwise. The resulting matrix is

\[\begin{array}{cc} & \begin{array}{ccccc} 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \end{array} \\ \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1 \\ 2 \\ 3 \\ 4 \\ 5 \\ 6 \end{array} & \left(\begin{array}{ccccc} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{array}\right) \end{array}\]

We call it the incidence matrix for the function \(f\).

hands-on exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\label{he:defnfcn-06}\)

"Plot” the graph of \(g\) in Hands-On Exercise 5.2.5

Summary and Review

- A function \(f\) from a set \(A\) to a set \(B\) (called the domain and the codomain, respectively) is a rule that describes how a value in the codomain \(B\) is assigned to an element from the domain \(A\).

- But it is not just any rule; rather, the rule must assign to every element \(x\) in the domain a unique value in the codomain.

- This unique value is called the image of \(x\) under the function \(f\), and is denoted \(f(x)\).

- We use the notation \({f}:{A}\to{B}\) to indicate that the name of the function is \(f\), the domain is \(A\), and the codomain is \(B\).

- A function \({f}:{A}\to{B}\) is the collection of all ordered pairs \((x,y)\) from \(A\times B\) such that \(y=f(x)\).

- The graph of a function may not be a curve, as in the case of a real function. It can be just a collection of points.

- We can also display the images of a function in a table, or represent the function with an incidence matrix.

Exercises

exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\label{ex:defnfcn-01}\)

What subset \(A\) of \(\mathbb{R}\) would you use to make \({f}:{A}\to{\mathbb{R}}\) defined by \(f(x) = \sqrt{3x-7}\) a function?

- Answer

-

\(\big[\frac{7}{3},\infty\big)\)

exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\label{ex:defnfcn-02}\)

What subset \(A\) of \(\mathbb{R}\) would you use to make

- \({g}:{A}\to{\mathbb{R}}\), where \(g(x) = \sqrt{(x-3)(x-7)}\)

- \({h}:{A}\to{\mathbb{R}}\), where \(h(x) = \frac{x+2}{\sqrt{(x-2)(5-x)}}\)

functions?

exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\label{ex:defnfcn-03}\)

Which of these data support a function from \(\{1,2,3,4\}\) to \(\{1,2,3,4\}\)? Explain.

\[\begin{array}{|c||c|c|c|} \hline x & 1 & 2 & 3 \\ \hline f(x) & 3 & 4 & 2 \\ \hline \end{array} \hskip0.4in \begin{array}{|c||c|c|c|c|} \hline x & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\ \hline g(x) & 2 & 4 & 3 & 2 \\ \hline \end{array} \hskip0.4in \begin{array}{|c||c|c|c|c|c|} \hline x & 1 & 2 & 3 & 3 & 4 \\ \hline h(x) & 2 & 4 & 3 & 2 & 3 \\ \hline \end{array}\]

- Answer

-

Only \(g\) is a function. The image \(f(4)\) is undefined, and there are two values for \(h(3)\). Hence, both \(f\) and \(h\) are not well-defined functions.

exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\label{ex:defnfcn-04}\)

(a) Use arrow diagrams to show three different functions from \(\{1,2,3,4\}\) to \(\{1,2,3,4\}\).

(b) How many different functions from \(\{1,2,3,4\}\) to \(\{1,2,3,4\}\) are possible?

exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\label{ex:defnfcn-05}\)

Determine whether these are functions. Explain.

- \({f}:{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\), where \(f(x) = \frac{3}{x^2+5}\).

- \({g}:{(5,\infty)}\to{\mathbb{R}}\), where \(g(x) = \frac{7}{\sqrt{x-4}}\).

- \({h}:{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\), where \(h(x) = -\sqrt{7-4x+4x^2}\).

- Answer

-

(a) Yes, because no division by zero will ever occur.

exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\label{ex:defnfcn-06}\)

Determine whether these are functions. Explain.

- \({s}:{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\), where \( x^2+[s(x)]^2=9\).

- \({t}:{\mathbb{R}}\to{\mathbb{R}}\), where \(|x-t(x)|=4\).

exercise \(\PageIndex{7}\label{ex:defnfcn-07}\)

Use arrow diagrams to show two different functions from \(\{a,b,c,d\}\) to \(\{1,2,3,4,5,6\}\).

- Answer

-

answers will vary

exercise \(\PageIndex{8}\label{ex:defnfcn-08}\)

Let \(T\) be your family tree that includes your biological mother, your maternal grandmother, your maternal great-grandmother, and so on, and all of their female descendants. Determine which of the following define a function from \(T\) to \(T\).

- \({h_1}:{T}\to{T}\), where \(h_1(x)\) is the mother of \(x\).

- \({h_2}:{T}\to{T}\), where \(h_2(x)\) is \(x\)’s sister.

- \({h_3}:{T}\to{T}\), where \(h_3(x)\) is an aunt of \(x\).

- \({h_4}:{T}\to{T}\), where \(h_4(x)\) is the eldest daughter of \(x\)’s maternal grandmother.

exercise \(\PageIndex{9}\label{ex:defnfcn-09}\)

For each of the following functions, determine the image of the given \(x\).

- \({k_1}:{\mathbb{N}-\{1\}}\to{\mathbb{N}}\), \(k_1(x)=\mbox{smallest prime factor of }x \), \(x=217\).

- \({k_2}:{\mathbb{Z}_{11}}\to{\mathbb{Z}_{11}}\), \(k_2(x)\equiv3x\) (mod 11), \(x=6\).

- \({k_3}:{\mathbb{Z}_{15}}\to{\mathbb{Z}_{15}}\), \(k_3(x)\equiv3x\) (mod 15), \(x=6\).

- Answer

-

(a) 7 (b) 7 (c) 3

exercise \(\PageIndex{10}\label{ex:defnfcn-10}\)

For each of the following functions, determine the images of the given \(x\)-values.

- \({\ell_1}:{\mathbb{Z}}\to{\mathbb{Z}}\), \(\ell_1(x)=x\bmod7\), \(x=250\), \(x=0\), and \(x=-16\).

Remark: Recall that, without parentheses, the notation “mod” means the binary operation mod.

\({\ell_2}:{\mathbb{Z}}\to{\mathbb{Z}}\), \(\ell_2(x)=\gcd(x,24)\), \(x=100\), \(x=0\), and \(x=-21\).