5.3: Non-right Triangles - Law of Sines

- Page ID

- 61267

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Understand how both forms of the Law of Sines are obtained.

- Apply the Law of Sines when you know two angles and a non-included side and if you know two angles and the included side.

- Use the Law of Sines in real-world and applied problems.

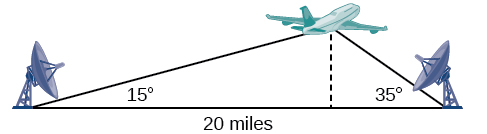

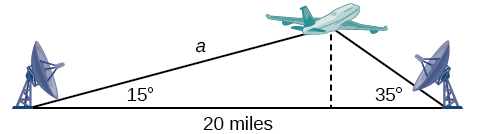

Suppose two radar stations located \(20\) miles apart each detect an aircraft between them. The angle of elevation measured by the first station is \(35\) degrees, whereas the angle of elevation measured by the second station is \(15\) degrees. How can we determine the altitude of the aircraft? We see in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) that the triangle formed by the aircraft and the two stations is not a right triangle, so we cannot use what we know about right triangles. In this section, we will find out how to solve problems involving non-right triangles.

Using the Law of Sines to Solve Oblique Triangles

In any triangle, we can draw an altitude, a perpendicular line from one vertex to the opposite side, forming two right triangles. It would be preferable, however, to have methods that we can apply directly to non-right triangles without first having to create right triangles.

Any triangle that is not a right triangle is an oblique triangle. Solving an oblique triangle means finding the measurements of all three angles and all three sides. To do so, we need to start with at least three of these values, including at least one of the sides. We will investigate three possible oblique triangle problem situations:

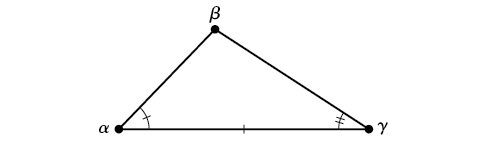

ASA (angle-side-angle) We know the measurements of two angles and the included side. See Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

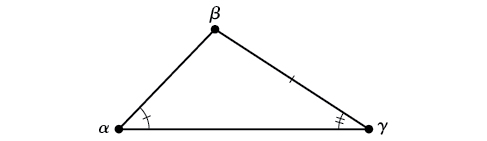

AAS (angle-angle-side) We know the measurements of two angles and a side that is not between the known angles. See Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

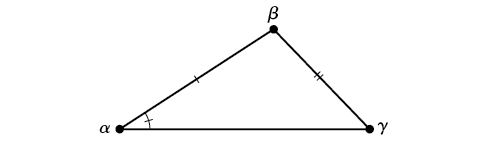

SSA (side-side-angle) We know the measurements of two sides and an angle that is not between the known sides. See Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

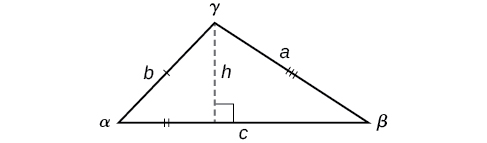

Knowing how to approach each of these situations enables us to solve oblique triangles without having to drop a perpendicular to form two right triangles. Instead, we can use the fact that the ratio of the measurement of one of the angles to the length of its opposite side will be equal to the other two ratios of angle measure to opposite side. Let’s see how this statement is derived by considering the triangle shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

Using the right triangle relationships, we know that \(\sin \alpha=\dfrac{h}{b}\) and \(\sin \beta=\dfrac{h}{a}\). Solving both equations for \(h\) gives two different expressions for \(h\).

\(h=b \sin \alpha\) and \(h=a \sin \beta\)

We then set the expressions equal to each other.

\[\begin{align*} b \sin \alpha&= a \sin \beta\\ \left(\dfrac{1}{ab}\right)\left(b \sin \alpha\right)&= \left(a \sin \beta\right)\left(\dfrac{1}{ab}\right)\qquad \text{Multiply both sides by } \dfrac{1}{ab}\\ \dfrac{\sin \alpha}{a}&= \dfrac{\sin \beta}{b} \end{align*}\]

Similarly, we can compare the other ratios.

\(\dfrac{\sin \alpha}{a}=\dfrac{\sin \gamma}{c}\) and \(\dfrac{\sin \beta}{b}=\dfrac{\sin \gamma}{c}\)

Collectively, these relationships are called the Law of Sines.

\(\dfrac{\sin \alpha}{a}=\dfrac{\sin \beta}{b}=\dfrac{\sin \gamma}{c}\)

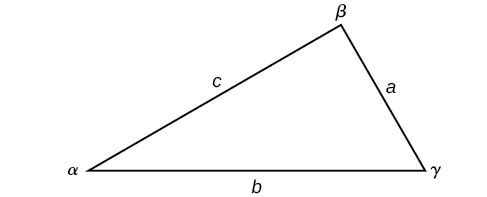

Note the standard way of labeling triangles: angle \(\alpha\) (alpha) is opposite side \(a\); angle \(\beta\) (beta) is opposite side \(b\); and angle \(\gamma\) (gamma) is opposite side \(c\). See Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

While calculating angles and sides, be sure to carry the exact values through to the final answer. Generally, final answers are rounded to the nearest tenth, unless otherwise specified.

LAW OF SINES

Given a triangle with angles and opposite sides labeled as in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), the ratio of the measurement of an angle to the length of its opposite side will be equal to the other two ratios of angle measure to opposite side. All proportions will be equal. The Law of Sines is based on proportions and is presented symbolically two ways.

\[\dfrac{\sin \alpha}{a}=\dfrac{\sin \beta}{b}=\dfrac{\sin \gamma}{c}\]

\[\dfrac{a}{\sin \alpha}=\dfrac{b}{\sin \beta}=\dfrac{c}{\sin \gamma}\]

To solve an oblique triangle, use any pair of applicable ratios.

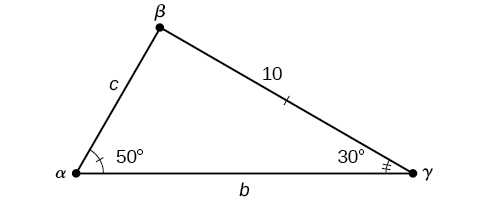

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Solving for Two Unknown Sides and Angle of an AAS Triangle

Solve the triangle shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) to the nearest tenth.

Solution

The three angles must add up to 180 degrees. From this, we can determine that

\[\begin{align*} \beta &= 180^{\circ} - 50^{\circ} - 30^{\circ}\\ &= 100^{\circ} \end{align*}\]

To find an unknown side, we need to know the corresponding angle and a known ratio. We know that angle \(\alpha=50°\)and its corresponding side \(a=10\). We can use the following proportion from the Law of Sines to find the length of \(c\).

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{\sin(50^{\circ})}{10}&= \dfrac{\sin(30^{\circ})}{c}\\ c\dfrac{\sin(50^{\circ})}{10}&= \sin(30^{\circ})\qquad \text{Multiply both sides by } c\\ c&= \sin(30^{\circ})\dfrac{10}{\sin(50^{\circ})}\qquad \text{Multiply by the reciprocal to isolate } c\\ c&\approx 6.5 \end{align*}\]

Similarly, to solve for \(b\), we set up another proportion.

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{\sin(50^{\circ})}{10}&= \dfrac{\sin(100^{\circ})}{b}\\ b \sin(50^{\circ})&= 10 \sin(100^{\circ})\qquad \text{Multiply both sides by } b\\ b&= \dfrac{10 \sin(100^{\circ})}{\sin(50^{\circ})}\qquad \text{Multiply by the reciprocal to isolate }b\\ b&\approx 12.9 \end{align*}\]

Therefore, the complete set of angles and sides is

\(\begin{matrix} \alpha=50^{\circ} & a=10\\ \beta=100^{\circ} & b\approx 12.9\\ \gamma=30^{\circ} & c\approx 6.5 \end{matrix}\)

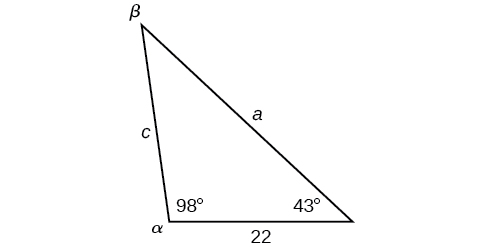

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Solve the triangle shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) to the nearest tenth.

- Answer

-

\(\begin{matrix} \alpha=98^{\circ} & a=34.6\\ \beta=39^{\circ} & b=22\\ \gamma=43^{\circ} & c=23.8 \end{matrix}\)

Using The Law of Sines to Solve SSA Triangles

We can use the Law of Sines to solve any oblique triangle, but some solutions may not be straightforward. In some cases, more than one triangle may satisfy the given criteria, which we describe as an ambiguous case. Triangles classified as SSA, those in which we know the lengths of two sides and the measurement of the angle opposite one of the given sides, may result in one or two solutions, or even no solution.

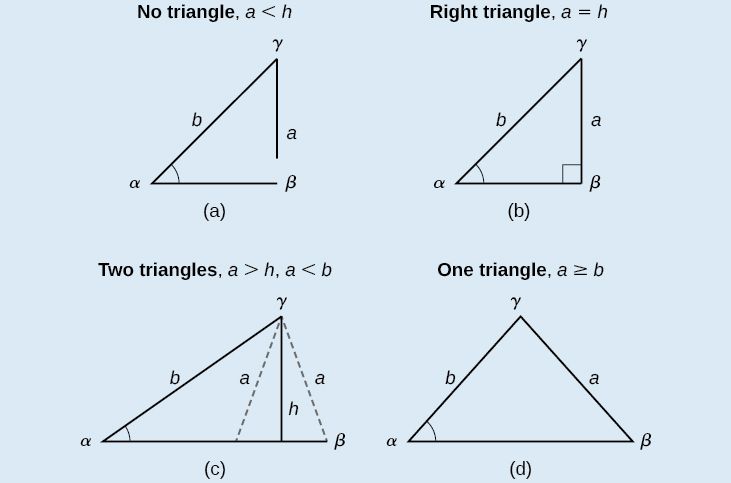

POSSIBLE OUTCOMES FOR SSA TRIANGLES

Oblique triangles in the category SSA may have four different outcomes. Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) illustrates the solutions with the known sides \(a\) and \(b\) and known angle \(\alpha\).

Solving an Oblique SSA Triangle

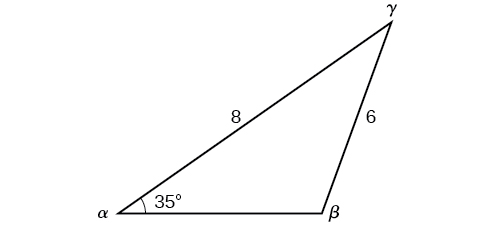

Solve the triangle in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) for the missing side and find the missing angle measures to the nearest tenth.

Solution

Use the Law of Sines to find angle \(\beta\) and angle \(\gamma\), and then side \(c\). Solving for \(\beta\), we have the proportion

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{\sin \alpha}{a}&= \dfrac{\sin \beta}{b}\\ \dfrac{\sin(35^{\circ})}{6}&= \dfrac{\sin \beta}{8}\\ \dfrac{8 \sin(35^{\circ})}{6}&= \sin \beta\\ 0.7648&\approx \sin \beta\\ {\sin}^{-1}(0.7648)&\approx 49.9^{\circ}\\ \beta&\approx 49.9^{\circ} \end{align*}\]

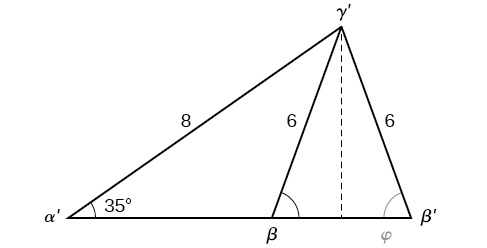

However, in the diagram, angle \(\beta\) appears to be an obtuse angle and may be greater than \(90°\). How did we get an acute angle, and how do we find the measurement of \(\beta\)? Let’s investigate further. Dropping a perpendicular from \(\gamma\) and viewing the triangle from a right angle perspective, we have Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\). It appears that there may be a second triangle that will fit the given criteria.

The angle supplementary to \(\beta\) is approximately equal to \(49.9°\), which means that \(\beta=180°−49.9°=130.1°\). (Remember that the sine function is positive in both the first and second quadrants.) Solving for \(\gamma\), we have

\[\begin{align*} \gamma&= 180^{\circ}-35^{\circ}-130.1^{\circ}\\ &\approx 14.9^{\circ} \end{align*}\]

We can then use these measurements to solve the other triangle. Since \(\gamma′\) is supplementary to \(\gamma\), we have

\[\begin{align*} \gamma^{'}&= 180^{\circ}-35^{\circ}-49.5^{\circ}\\ &\approx 95.1^{\circ} \end{align*}\]

Now we need to find \(c\) and \(c′\).

We have

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{c}{\sin(14.9^{\circ})}&= \dfrac{6}{\sin(35^{\circ})}\\ c&= \dfrac{6 \sin(14.9^{\circ})}{\sin(35^{\circ})}\\ &\approx 2.7 \end{align*}\]

Finally,

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{c'}{\sin(95.1^{\circ})}&= \dfrac{6}{\sin(35^{\circ})}\\ c'&= \dfrac{6 \sin(95.1^{\circ})}{\sin(35^{\circ})}\\ &\approx 10.4 \end{align*}\]

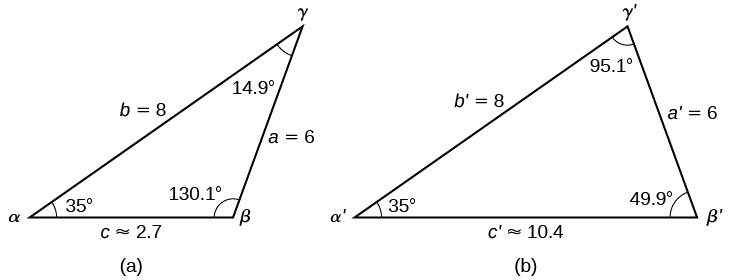

To summarize, there are two triangles with an angle of \(35°\), an adjacent side of 8, and an opposite side of 6, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\).

However, we were looking for the values for the triangle with an obtuse angle \(\beta\). We can see them in the first triangle (a) in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Given \(\alpha=80°\), \(a=120\), and \(b=121\), find the missing side and angles. If there is more than one possible solution, show both.

- Answer

-

Solution 1

\(\begin{matrix} \alpha=80^{\circ} & a=120\\ \beta\approx 83.2^{\circ} & b=121\\ \gamma\approx 16.8^{\circ} & c\approx 35.2 \end{matrix}\)

Solution 2

\(\begin{matrix} \alpha '=80^{\circ} & a'=120\\ \beta '\approx 96.8^{\circ} & b'=121\\ \gamma '\approx 3.2^{\circ} & c'\approx 6.8 \end{matrix}\)

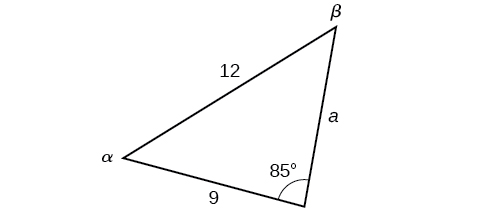

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Solving for the Unknown Sides and Angles of a SSA Triangle

In the triangle shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\), solve for the unknown side and angles. Round your answers to the nearest tenth.

Solution

In choosing the pair of ratios from the Law of Sines to use, look at the information given. In this case, we know the angle, \(\gamma=85°\), and its corresponding side \(c=12\), and we know side \(b=9\). We will use this proportion to solve for \(\beta\).

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{\sin(85^{\circ})}{12}&= \dfrac{\sin \beta}{9}\qquad \text{Isolate the unknown.}\\ \dfrac{9 \sin(85^{\circ})}{12}&= \sin \beta \end{align*}\]

To find \(\beta\), apply the inverse sine function. The inverse sine will produce a single result, but keep in mind that there may be two values for \(\beta\). It is important to verify the result, as there may be two viable solutions, only one solution (the usual case), or no solutions.

\[\begin{align*} \beta&= {\sin}^{-1}\left(\dfrac{9 \sin(85^{\circ})}{12}\right)\\ \beta&\approx {\sin}^{-1} (0.7471)\\ \beta&\approx 48.3^{\circ} \end{align*}\]

In this case, if we subtract \(\beta\) from \(180°\), we find that there may be a second possible solution. Thus, \(\beta=180°−48.3°≈131.7°\). To check the solution, subtract both angles, \(131.7°\) and \(85°\), from \(180°\). This gives

\[\begin{align*} \alpha&= 180^{\circ}-85^{\circ}-131.7^{\circ}\\ &\approx -36.7^{\circ} \end{align*}\]

which is impossible, and so \(\beta≈48.3°\).

To find the remaining missing values, we calculate \(\alpha=180°−85°−48.3°≈46.7°\). Now, only side \(a\) is needed. Use the Law of Sines to solve for \(a\) by one of the proportions.

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{\sin(85°)}{12}&= \dfrac{\sin(46.7^{\circ})}{a}\\ a\dfrac{\sin(85^{\circ})}{12}&= \sin(46.7^{\circ})\\ a&=\dfrac{12\sin(46.7^{\circ})}{\sin(85^{\circ})}\\ &\approx 8.8 \end{align*}\]

The complete set of solutions for the given triangle is

\(\begin{matrix} \alpha\approx 46.7^{\circ} & a\approx 8.8\\ \beta\approx 48.3^{\circ} & b=9\\ \gamma=85^{\circ} & c=12 \end{matrix}\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Given \(\alpha=80°\), \(a=100\), \(b=10\), find the missing side and angles. If there is more than one possible solution, show both. Round your answers to the nearest tenth.

- Answer

-

\(\beta≈5.7°\), \(\gamma≈94.3°\), \(c≈101.3\)

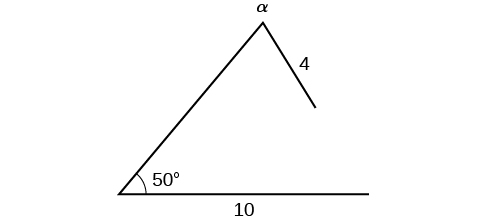

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Finding the Triangles That Meet the Given Criteria

Find all possible triangles if one side has length \(4\) opposite an angle of \(50°\), and a second side has length \(10\).

Solution

Using the given information, we can solve for the angle opposite the side of length \(10\). See Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\).

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{\sin \alpha}{10}&= \dfrac{\sin(50^{\circ})}{4}\\ \sin \alpha&= \dfrac{10 \sin(50^{\circ})}{4}\\ \sin \alpha&\approx 1.915 \end{align*}\]

We can stop here without finding the value of \(\alpha\). Because the range of the sine function is \([ −1,1 ]\), it is impossible for the sine value to be \(1.915\). In fact, inputting \({\sin}^{−1}(1.915)\) in a graphing calculator generates an ERROR DOMAIN. Therefore, no triangles can be drawn with the provided dimensions.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Determine the number of triangles possible given \(a=31\), \(b=26\), \(\beta=48°\).

- Answer

-

two

Solving Applied Problems Using the Law of Sines

The more we study trigonometric applications, the more we discover that the applications are countless. Some are flat, diagram-type situations, but many applications in calculus, engineering, and physics involve three dimensions and motion.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Finding an Altitude

Find the altitude of the aircraft in the problem introduced at the beginning of this section, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\). Round the altitude to the nearest tenth of a mile.

Solution

To find the elevation of the aircraft, we first find the distance from one station to the aircraft, such as the side \(a\), and then use right triangle relationships to find the height of the aircraft, \(h\).

Because the angles in the triangle add up to \(180\) degrees, the unknown angle must be \(180°−15°−35°=130°\). This angle is opposite the side of length \(20\), allowing us to set up a Law of Sines relationship.

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{\sin(130^{\circ})}{20}&= \dfrac{\sin(35^{\circ})}{a}\\ a \sin(130^{\circ})&= 20 \sin(35^{\circ})\\ a&= \dfrac{20 \sin(35^{\circ})}{\sin(130^{\circ})}\\ a&\approx 14.98 \end{align*}\]

The distance from one station to the aircraft is about \(14.98\) miles.

Now that we know \(a\), we can use right triangle relationships to solve for \(h\).

\[\begin{align*} \sin(15^{\circ})&= \dfrac{opposite}{hypotenuse}\\ \sin(15^{\circ})&= \dfrac{h}{a}\\ \sin(15^{\circ})&= \dfrac{h}{14.98}\\ h&= 14.98 \sin(15^{\circ})\\ h&\approx 3.88 \end{align*}\]

The aircraft is at an altitude of approximately \(3.9\) miles.

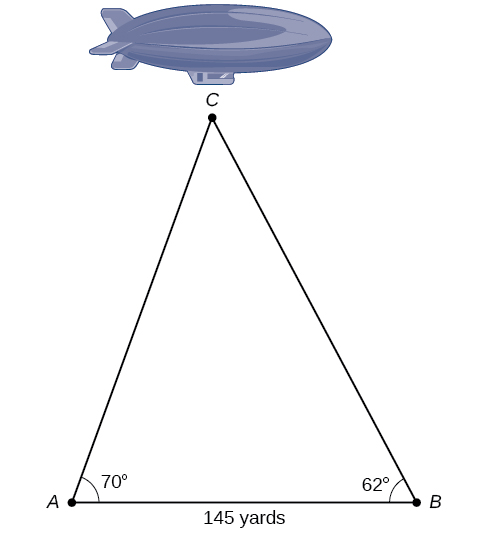

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

The diagram shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) represents the height of a blimp flying over a football stadium. Find the height of the blimp if the angle of elevation at the southern end zone, point A, is \(70°\), the angle of elevation from the northern end zone, point B, is \(62°\), and the distance between the viewing points of the two end zones is \(145\) yards.

- Answer

-

\(161.9\) yd.

Key Equations

|

Law of Sines |

\(\dfrac{\sin \alpha}{a}=\dfrac{\sin \beta}{b}=\dfrac{\sin \gamma}{c}\) \(\dfrac{a}{\sin \alpha}=\dfrac{b}{\sin \beta}=\dfrac{c}{\sin \gamma}\) |

Key Concepts

- The Law of Sines can be used to solve oblique triangles, which are non-right triangles.

- According to the Law of Sines, the ratio of the measurement of one of the angles to the length of its opposite side equals the other two ratios of angle measure to opposite side.

- There are three possible cases: ASA, AAS, SSA. Depending on the information given, we can choose the appropriate equation to find the requested solution. See Example \(\PageIndex{1}\).

- The ambiguous case arises when an oblique triangle can have different outcomes.

- There are three possible cases that arise from SSA arrangement—a single solution, two possible solutions, and no solution. See Example \(\PageIndex{2}\) and Example \(\PageIndex{3}\).

- The Law of Sines can be used to solve triangles with given criteria. See Example \(\PageIndex{4}\).

- There are many trigonometric applications. They can often be solved by first drawing a diagram of the given information and then using the appropriate equation. See Example \(\PageIndex{6}\).

Contributors and Attributions

Jay Abramson (Arizona State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/precalculus.