24.2: Resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas

- Page ID

- 127788

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Forma estándar de una ecuación cuadrática

En el Capítulo 5 estudiamos ecuaciones lineales en una y dos variables y métodos para resolverlas. Observamos que una ecuación lineal en una variable era cualquier ecuación que pudiera escribirse en la forma\(ax + b = 0, a\not = 0\), y una ecuación lineal en dos variables era cualquier ecuación que pudiera escribirse en la forma\(ax + by = c\), donde\(a\) y no\(b\) son ambas\(0\). Ahora queremos estudiar ecuaciones cuadráticas en una variable.

Una ecuación cuadrática es una ecuación de la forma\(ax^2 + bx + c = 0, a \not = 0\).

La forma estándar de la ecuación cuadrática es\(ax^2 + bx + c = 0, a \not = 0\).

Para una ecuación cuadrática en forma estándar\(ax^2 + bx + c = 0\),

\(a\)es el coeficiente de\(x^2\).

\(b\)es el coeficiente de\(x\).

\(c\)es el término constante.

Conjunto de Muestras A

Las siguientes son ecuaciones cuadráticas.

\(3x^2 + 2x - 1 = 0\). \(a = 3, b = 2, c = -1\)

\(5x^2 + 8x = 0\). \(a = 5, b = 8, c = 0\)

Observe que esta ecuación podría ser escrita\(5x^2 + 8x + 0 = 0\). Ahora es claro que\(c = 0\).

\(x^2 + 7 = 0\). \(a = 1, b = 0, c = 7\).

Observe que esta ecuación podría ser escrita\(x^2 + 0x + 7 = 0\). Ahora es claro que\(b = 0\)

Las siguientes no son ecuaciones cuadráticas.

\(3x + 2 = 0\). \(a = 0\). Esta ecuación es lineal.

\(8x^2 + \dfrac{3}{x} - 5 = 0\)

La expresión en el lado izquierdo del signo igual tiene una variable en el denominador y, por lo tanto, no es cuadrática.

Conjunto de práctica A

¿Cuáles de las siguientes ecuaciones son ecuaciones cuadráticas? Responda “sí” o “no” a cada ecuación.

\(6x^2 - 4x + 9 = 0\)

- Responder

-

si

\(5x+8=0\)

- Responder

-

no

\(4x^3 - 5x^2 + x + 6 = 8\)

- Responder

-

no

\(4x^2 - 2x + 4 = 1\)

- Responder

-

si

\(\dfrac{2}{x} - 5x^2 = 6x + 4\)

- Responder

-

no

\(9x^2 - 2x + 6 = 4x^2 + 8\)

- Responder

-

si

Propiedad de factor cero

Nuestro objetivo es resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas. El método para resolver ecuaciones cuadráticas se basa en la propiedad de factor cero de los números reales. Nos presentaron a la propiedad de factor cero en la Sección 8.2. Lo declaramos de nuevo.

Si dos números\(a\) y\(b\) se multiplican juntos y el producto resultante es\(0\), entonces al menos uno de los números debe ser\(0\). Álgebraicamente, si\(a \cdot b = 0\), entonces\(a = 0\) o ambos\(a = 0\) y\(b = 0\).

Conjunto de Muestras B

Utilice la propiedad de factor cero para resolver cada ecuación.

Si\(9x = 0\), entonces\(x\) debe ser\(0\).

Si\(-2x^2 = 0\), entonces\(x^2 = 0, x = 0\)

Si\(5\) entonces\(x-1\) debe ser\(0\), ya que no\(5\) es cero.

\ (\ begin {array} {Flushleft}

x - 1 &= 0\\

x &= 1

\ end {array}\)

Si\(x(x+6) = 0\), entonces

\ (\ begin {array} {Flushleft}

x &= 0 &\ text {o} & x+6&=0\\

x&=0, -6 && x &= -6

\ end {array}\)

Si\((x+2)(x+3) = 0\), entonces

\ (\ begin {array} {Flushleft}

x + 2 &= 0 &\ text {o} & x + 3 &= 0\\

x &= -2 && x &= -3\\

x &= -2, -3

\ end {array}\)

Si\((x+10)(4x - 5) = 0\), entonces

\ (\ begin {array} {Flushleft}

x + 10 &= 0 &\ text {o} & 4x - 5 &= 0\\

x &= -10 && 4x &= 5\\

x &= -10,\ dfrac {5} {4} && x &=\ dfrac {5} {4}

\ end {array}\)

Set de práctica B

Utilice la propiedad de factor cero para resolver cada ecuación.

\(6(a−4)=0\)

- Responder

-

\(a=4\)

\((y+6)(y−7)=0\)

- Responder

-

\(y=−6, 7\)

\((x+5)(3x−4)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(x = -5, \dfrac{4}{3}\)

Ejercicios

Para los siguientes problemas, escriba los valores de\(a\),\(b\), y\(c\) en ecuaciones cuadráticas.

\(3x^2 + 4x - 7 = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(3,4,−7\)

\(7x^2 + 2x + 8 = 0\)

\(2y^2 - 5y + 5 = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(2,−5,5\)

\(7a^2 + a - 8 = 0\).

\(-3a^2 + 4a - 1 = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(−3,4,−1\)

\(7b^2 + 3b + 0\)

\(2x^2 + 5x + 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(2, 5, 0\)

\(4y^2 + 9 = 0\)

\(8a^2 - 2a = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(8,−2,0\)

\(6x^2 = 0\)

\(4y^2 = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(4, 0, 0\)

\(5x^2 - 3x + 9 = 4x^2\)

\(7x^2 + 2x + 1 = 6x^2 + x - 9\)

- Contestar

-

\(1, 1, 10\)

\(-3x^2 + 4x - 1 = -4x^2 - 4x + 12\)

\(5x - 7 = -3x^2\)

- Contestar

-

\(3,5,−7\)

\(3x - 7 = -2x^2 + 5x\)

\(0 = x^2 + 6x - 1\)

- Contestar

-

\(1,6,−1\)

\(9 = x^2\)

\(x^2 = 9\)

- Contestar

-

\(1,0,−9\)

\(0 = -x ^2\)

Para los siguientes problemas, utilice la propiedad de factor cero para resolver las ecuaciones.

\(4x = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(x=0\)

\(16y=0\)

\(9a=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(a=0\)

\(4m=0\)

\(3(k+7)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(k=−7\)

\(8(y−6)=0\)

\(−5(x+4)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(x=−4\)

\(−6(n+15)=0\)

\(y(y−1)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(y=0,1\)

\(a(a−6)=0\)

\(n(n+4)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(n=0,−4\)

\(x(x+8)=0\)

\(9(a−4)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(a=4\)

\(−2(m+11)=0\)

\(x(x+7) = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(x=−7 \text{ or } x=0\)

\(n(n−10)=0\)

\((y−4)(y−8)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(y=4 \text{ or } y=8\)

\((k−1)(k−6)=0\)

\((x+5)(x+4)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(x=−4 \text{ or } x=−5\)

\((y+6)(2y+1)=0\)

\((x−3)(5x−6)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(x = \dfrac{6}{5} \text{ or } x = 3\)

\((5a+1)(2a−3)=0\)

\((6m+5)(11m−6)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(m = -\dfrac{5}{6} \text{ or } m = \dfrac{6}{11}\)

\((2m−1)(3m+8)=0\)

\((4x+5)(2x−7)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(x = \dfrac{-5}{4}, \dfrac{7}{2}\)

\((3y + 1)(2y + 1) = 0\)

\((7a + 6)(7a - 6) = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(a = \dfrac{-6}{7}, \dfrac{6}{7}\)

\((8x+11)(2x−7)=0\)

\((5x−14)(3x+10)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(x = \dfrac{14}{5}, \dfrac{-10}{3}\)

\((3x−1)(3x−1)=0\)

\((2y+5)(2y+5)=0\)

- Contestar

-

\(y = \dfrac{-5}{2}\)

\((7a - 2)^2 = 0\)

\((5m - 6)^2 = 0\)

- Contestar

-

\(m = \dfrac{6}{5}\)

Ejercicios para revisión

Factorial\(12ax - 3x + 8a - 2\) por agrupación.

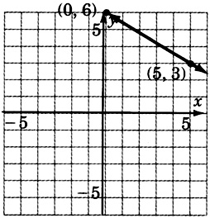

Construye la gráfica de\(6x + 10y - 60 = 0\)

- Contestar

-

Encuentra la diferencia:\(\dfrac{1}{x^2 + 2x + 1} - \dfrac{1}{x^2 - 1}\).

Simplificar\(\sqrt{7}(\sqrt{2} + 2)\)

- Contestar

-

\(\sqrt{14} + 2\sqrt{7}\)

Resolver la ecuación radical\(\sqrt{3x + 10} = x + 4\)