19.1: Lattices

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Partially Ordered Sets

We begin the study of lattices and Boolean algebras by generalizing the idea of inequality. Recall that a relation on a set X is a subset of X×X. A relation P on X is called a partial order of X if it satisfies the following axioms.

- The relation is reflexive: (a,a)∈P for all a∈X.

- The relation is antisymmetric: if (a,b)∈P and (b,a)∈P, then a=b.

- The relation is transitive: if (a,b)∈P and (b,c)∈P, then (a,c)∈P.

We will usually write a⪯b to mean (a,b)∈P unless some symbol is naturally associated with a particular partial order, such as a≤b with integers a and b, or A⊂B with sets A and B. A set X together with a partial order ⪯ is called a partially ordered set, or poset.

Example 19.1

The set of integers (or rationals or reals) is a poset where

Solution

a≤b has the usual meaning for two integers a and b in Z.

Example 19.2

Let X be any set. We will define the power set of X to be the set of all subsets of X. We denote the power set of X by P(X). For example, let X={a,b,c}. Then

Solution

P(X) is the set of all subsets of the set {a,b,c}:

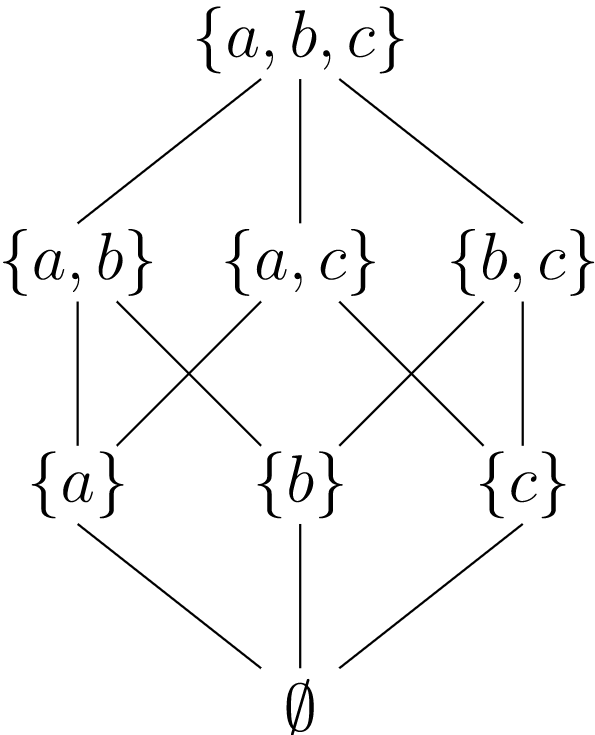

On any power set of a set X, set inclusion, ⊂, is a partial order. We can represent the order on {a,b,c} schematically by a diagram such as the one in Figure 19.3.

Figure 19.3. Partial order on P({a,b,c})

Example 19.4

Let G be a group. The set of subgroups of G is a

Solution

poset, where the partial order is set inclusion.

Example 19.5

There can be more than one partial order on a particular set. We can form a partial order on N by a⪯b if a∣b. The relation is certainly reflexive since a∣a for all a∈N. If m∣n and n∣m, then

Solution

m=n; hence, the relation is also antisymmetric. The relation is transitive, because if m∣n and n∣p, then m∣p.

Example 19.6

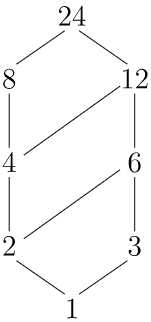

Let X={1,2,3,4,6,8,12,24} be the set of divisors of 24 with the partial order defined in Example 19.5.

Solution

Figure 19.7 shows the partial order on X.

Figure 19.7. A partial order on the divisors of 24

Let Y be a subset of a poset X. An element u in X is an upper bound of Y if a⪯u for every element a∈Y. If u is an upper bound of Y such that u⪯v for every other upper bound v of Y, then u is called a least upper bound or supremum of Y. An element l in X is said to be a lower bound of Y if l⪯a for all a∈Y. If l is a lower bound of Y such that k⪯l for every other lower bound k of Y, then l is called a greatest lower bound or infimum of Y.

Example 19.8

Let Y={2,3,4,6} be contained in the set X of Example 19.6. Then

Solution

Y has upper bounds 12 and 24, with 12 as a least upper bound. The only lower bound is 1; hence, it must be a greatest lower bound.

As it turns out, least upper bounds and greatest lower bounds are unique if they exist.

Theorem 19.9

Let Y be a nonempty subset of a poset X. If Y has a least upper bound, then Y has a unique least upper bound. If Y has a greatest lower bound, then Y has a unique greatest lower bound.

- Proof

-

Let u1 and u2 be least upper bounds for Y. By the definition of the least upper bound, u1⪯u for all upper bounds u of Y. In particular, u1⪯u2. Similarly, u2⪯u1. Therefore, u1=u2 by antisymmetry. A similar argument show that the greatest lower bound is unique.

On many posets it is possible to define binary operations by using the greatest lower bound and the least upper bound of two elements. A lattice is a poset L such that every pair of elements in L has a least upper bound and a greatest lower bound. The least upper bound of a,b∈L is called the join of a and b and is denoted by a∨b. The greatest lower bound of a,b∈L is called the meet of a and b and is denoted by a∧b.

Example 19.10

Let X be a set. Then the power set of X, P(X), is a lattice. For two sets

Solution

A and B in P(X), the least upper bound of A and B is A∪B. Certainly A∪B is an upper bound of A and B, since A⊂A∪B and B⊂A∪B. If C is some other set containing both A and B, then C must contain A∪B; hence, A∪B is the least upper bound of A and B. Similarly, the greatest lower bound of A and B is A∩B.

Example 19.11

Let G be a group and suppose that X is the set of subgroups of G. Then

Solution

X is a poset ordered by set-theoretic inclusion, ⊂. The set of subgroups of G is also a lattice. If H and K are subgroups of G, the greatest lower bound of H and K is H∩K. The set H∪K may not be a subgroup of G. We leave it as an exercise to show that the least upper bound of H and K is the subgroup generated by H∪K.

In set theory we have certain duality conditions. For example, by De Morgan's laws, any statement about sets that is true about (A∪B)′ must also be true about A′∩B′. We also have a duality principle for lattices.

Axiom 19.12. Principle of Duality

Any statement that is true for all lattices remains true when ⪯ is replaced by ⪰ and ∨ and ∧ are interchanged throughout the statement

The following theorem tells us that a lattice is an algebraic structure with two binary operations that satisfy certain axioms.

Theorem 19.13

If L is a lattice, then the binary operations ∨ and ∧ satisfy the following properties for a,b,c∈L.

- Commutative laws: a∨b=b∨a and a∧b=b∧a.

- Associative laws: a∨(b∨c)=(a∨b)∨c and a∧(b∧c)=(a∧b)∧c.

- Idempotent laws: a∨a=a and a∧a=a.

- Absorption laws: a∨(a∧b)=a and a∧(a∨b)=a.

- Proof

-

By the Principle of Duality, we need only prove the first statement in each part.

(1) By definition a∨b is the least upper bound of {a,b}, and b∨a is the least upper bound of {b,a}; however, {a,b}={b,a}.

(2) We will show that a∨(b∨c) and (a∨b)∨c are both least upper bounds of {a,b,c}. Let d=a∨b. Then c⪯d∨c=(a∨b)∨c. We also know that

a⪯a∨b=d⪯d∨c=(a∨b)∨c.A similar argument demonstrates that b⪯(a∨b)∨c. Therefore, (a∨b)∨c is an upper bound of {a,b,c}. We now need to show that (a∨b)∨c is the least upper bound of {a,b,c}. Let u be some other upper bound of {a,b,c}. Then a⪯u and b⪯u; hence, d=a∨b⪯u. Since c⪯u, it follows that (a∨b)∨c=d∨c⪯u. Therefore, (a∨b)∨c must be the least upper bound of {a,b,c}. The argument that shows a∨(b∨c) is the least upper bound of {a,b,c} is the same. Consequently, a∨(b∨c)=(a∨b)∨c.

(3) The join of a and a is the least upper bound of {a}; hence, a∨a=a.

(4) Let d=a∧b. Then a⪯a∨d. On the other hand, d=a∧b⪯a, and so a∨d⪯a. Therefore, a∨(a∧b)=a.

Given any arbitrary set L with operations ∨ and ∧, satisfying the conditions of the previous theorem, it is natural to ask whether or not this set comes from some lattice. The following theorem says that this is always the case.

Theorem 19.14

Let L be a nonempty set with two binary operations ∨ and ∧ satisfying the commutative, associative, idempotent, and absorption laws. We can define a partial order on L by a⪯b if a∨b=b. Furthermore, L is a lattice with respect to ⪯ if for all a,b∈L, we define the least upper bound and greatest lower bound of a and b by a∨b and a∧b, respectively.

- Proof

-

We first show that L is a poset under ⪯. Since a∨a=a, a⪯a and ⪯ is reflexive. To show that ⪯ is antisymmetric, let a⪯b and b⪯a. Then a∨b=b and b∨a=a. By the commutative law, b=a∨b=b∨a=a. Finally, we must show that ⪯ is transitive. Let a⪯b and b⪯c. Then a∨b=b and b∨c=c. Thus,

a∨c=a∨(b∨c)=(a∨b)∨c=b∨c=c,or a⪯c.

To show that L is a lattice, we must prove that a∨b and a∧b are, respectively, the least upper and greatest lower bounds of a and b. Since a=(a∨b)∧a=a∧(a∨b), it follows that a⪯a∨b. Similarly, b⪯a∨b. Therefore, a∨b is an upper bound for a and b. Let u be any other upper bound of both a and b. Then a⪯u and b⪯u. But a∨b⪯u since

(a∨b)∨u=a∨(b∨u)=a∨u=u.The proof that a∧b is the greatest lower bound of a and b is left as an exercise.