1.17: Angles

- Page ID

- 153121

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)You will need a calculator near the end of this module.

Angle Measure

Angle measurement is important in construction, surveying, physical therapy, and many other fields. We can visualize an angle as the figure formed when two line segments share a common endpoint.

We can also think about an angle as a measure of rotation. One full rotation or a full circle is \(360^\circ\), so a half rotation or U-turn is \(180^\circ\), and a quarter turn is \(90^\circ\). We often classify angles by their size relative to these \(90^\circ\) and \(180^\circ\) benchmarks.

Acute Angle: between \(0^\circ\) and \(90^\circ\)

Right Angle: exactly \(90^\circ\)

Obtuse Angle: between \(90^\circ\) and \(180^\circ\)

Straight Angle: exactly \(180^\circ\)

Reflexive Angle: between \(180^\circ\) and \(360^\circ\)

Identify each angle shown below as acute, right, obtuse, straight, or reflexive.

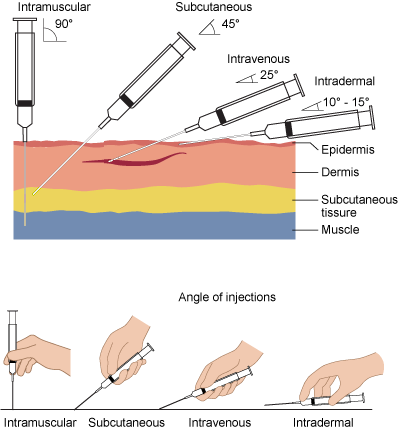

Lines that form a \(90^\circ\) angle are called perpendicular. As shown below, the needle should be perpendicular to the body surface for an intramuscular injection.

When lines cross, they form angles. No surprises there. If we know the measure of one angle, we may be able to determine the measures of the remaining angles using a little logic.

Find the measure of each unknown angle.

Angles in Triangles

If you need to find the measures of the angles in a triangle, there are a few rules that can help.

The sum of the angles of every triangle is \(180^\circ\).

If any sides of a triangle have equal lengths, then the angles opposite those sides will have equal measures.

Find the measures of the unknown angles in each triangle.

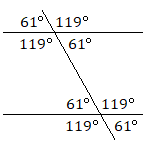

Angles and Parallel Lines

Two lines that point in the exact same direction and will never cross are called parallel lines. If two parallel lines are crossed by a third line, sets of equally-sized angles will be formed, as shown in the following diagram. All four acute angles will be equal in measure, all four obtuse angles will be equal in measure, and any acute angle and obtuse angle will have a combined measure of \(180^\circ\).

- Find the measures of angles \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\).

Degrees, Minutes, Seconds

It is possible to have angle measures that are not a whole number of degrees. It is common to use decimals in these situations, but the older method—which is called the degrees-minutes-seconds or DMS system—divides a degree using fractions out of \(60\): a minute is \(\dfrac{1}{60}\) of a degree, and a second is \(\dfrac{1}{60}\) of a minute, which means a second is \(\dfrac{1}{3,600}\) of a degree. (Fortunately, these units work exactly like time; think of \(1\) degree as \(1\) hour.) For example, \(2.5^\circ=2^\circ30’\).

We will look at the procedure for converting between systems, but there are online calculators such as the one at https://www.fcc.gov/media/radio/dms-decimal which will do the conversions for you.

If you have latitude and longitude in DMS, like N \(18^\circ54’40”\) W \(155^\circ40’51”\), and need to convert it to decimal degrees, the process is fairly simple with a calculator.

Converting from DMS to Decimal Degrees

Enter \(\text{degrees}+\text{minutes}\div60+\text{seconds}\div3600}\) in your calculator. Round the result to the fourth decimal place, if necessary.[1]

Convert each angle measurement from degrees-minutes-seconds into decimal form. Round to the nearest ten-thousandth, if necessary.

- \(18^\circ54’40”\)

- \(155^\circ40’51”\)

- \(34^\circ11’32.5”\)

Going from decimal degrees to DMS is a more complicated process.

Converting from Decimal Degrees to DMS

- The whole-number part of the angle measurement gives the number of degrees.

- Multiply the decimal part by \(60\). The whole number part of this result is the number of minutes.

- Multiply the decimal part of the minutes by \(60\). This gives the number of seconds (including any decimal part of seconds).

For example, let’s convert \(15.3740^\circ\).

- The degrees part of our answer will be \(15\).

- The decimal part times \(60\) is \(0.3740\cdot60=22.44\) minutes. The minutes part of our answer will be \(22\).

- The decimal part times \(60\) is \(0.44\cdot60=26.4\) seconds. The seconds part of our answer will be \(26.4\).

So \(15.3740^\circ=15^\circ22’26.4”\).

Convert each angle measurement from decimal into degrees-minutes-seconds form.

- \(29.9750^\circ\)

- \(31.1375^\circ\)

- \(76.3467^\circ\)

- We round to four decimal places because \(1\) second of angle is \(\dfrac{1}{3,600}\) of a degree. This is a smaller fraction than \(\dfrac{1}{1,000}\) so our precision is slightly better than the thousandths place. ↵