1.3: Angle Classifications

- Page ID

- 34119

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

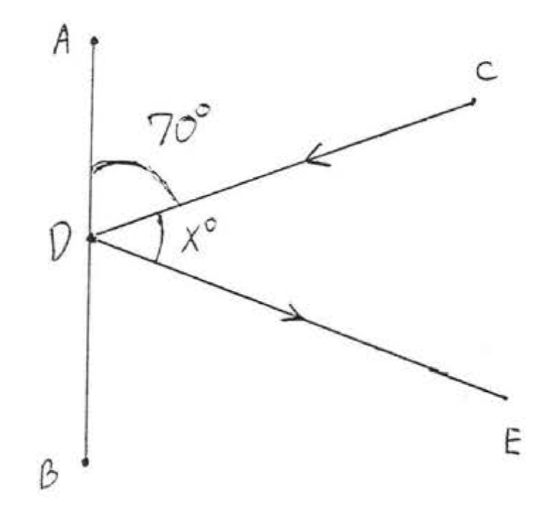

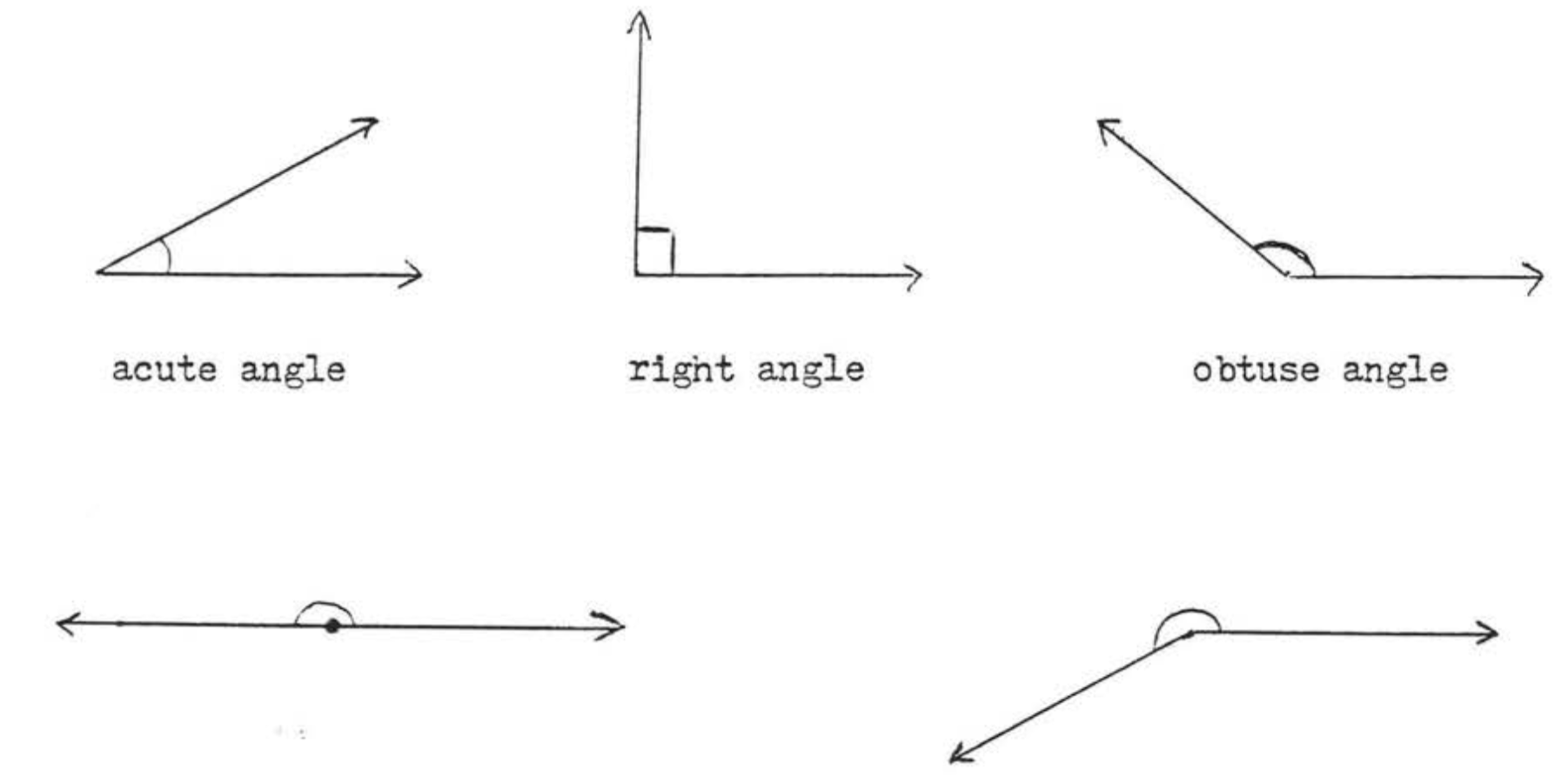

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Angles are classified according to their measures as follow:

- An acute angle is an angle whose measure is between \(0^{\circ}\) and \(90^{\circ}\).

- A right angle is an angle whose measure is \(90^{\circ}\). We often use a little square to indicate a right angle.

- An obtuse angle is an angle whose measure is between \(90^{\circ}\) and \(180^{\circ}\).

- A straight angle is an angle whose measure is \(180^{\circ}\). A straight angle is just a straight line with one of its points designated as the vertex.

- A reflex angle is an angle whose measure is greater than \(180^{\circ}\).

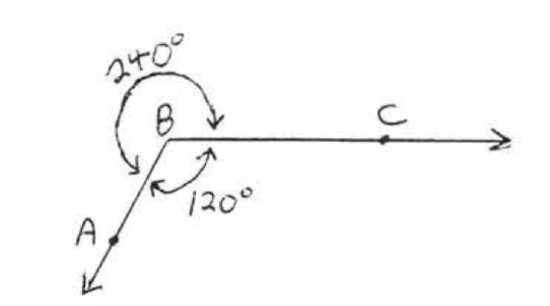

Notice that an angle can be measured in two ways. In Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), \(\angle ABC\) is a reflex of \(240^{\circ}\) or an obtuse angle of \(120^{\circ}\) depending on how it is measured. Unless otherwise indicated, we will always assume the angle has measure less than \(180^{\circ}\).

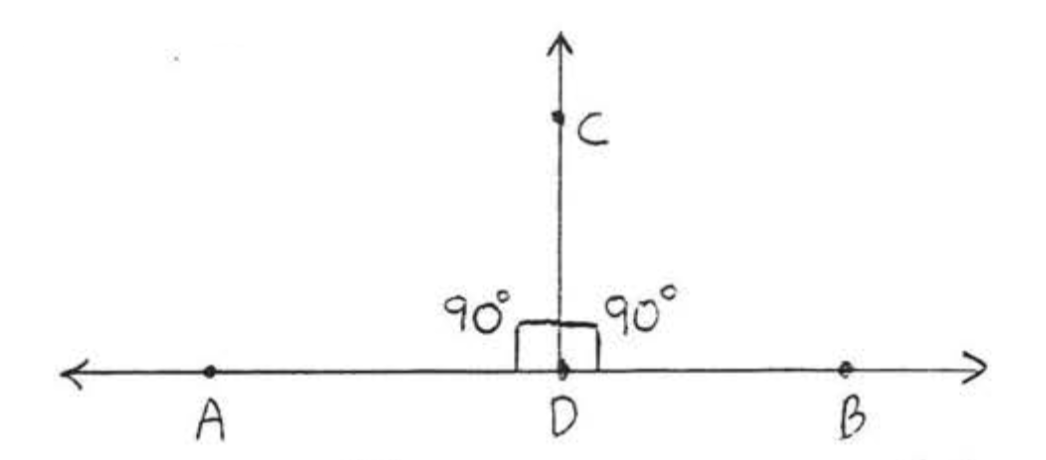

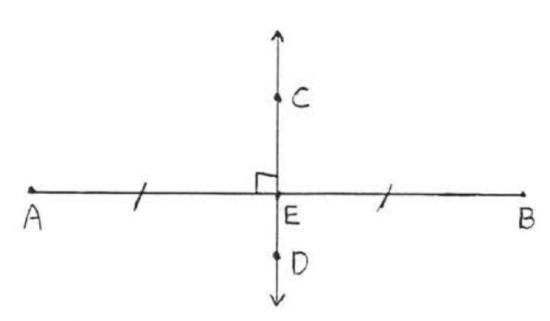

The lines are perpendicular if they meet to form right angles. In Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) is perpendicular to \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\). The symbol for perpendicular is \(\perp\) and we write \(\overleftrightarrow{AB} \perp \overleftrightarrow{CD}\).

The perpendicular bisector of a line segment is a line perpendicular to the line segment at its midpoint, In Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\), \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\) is a perpendicular bisector of \(AB\).

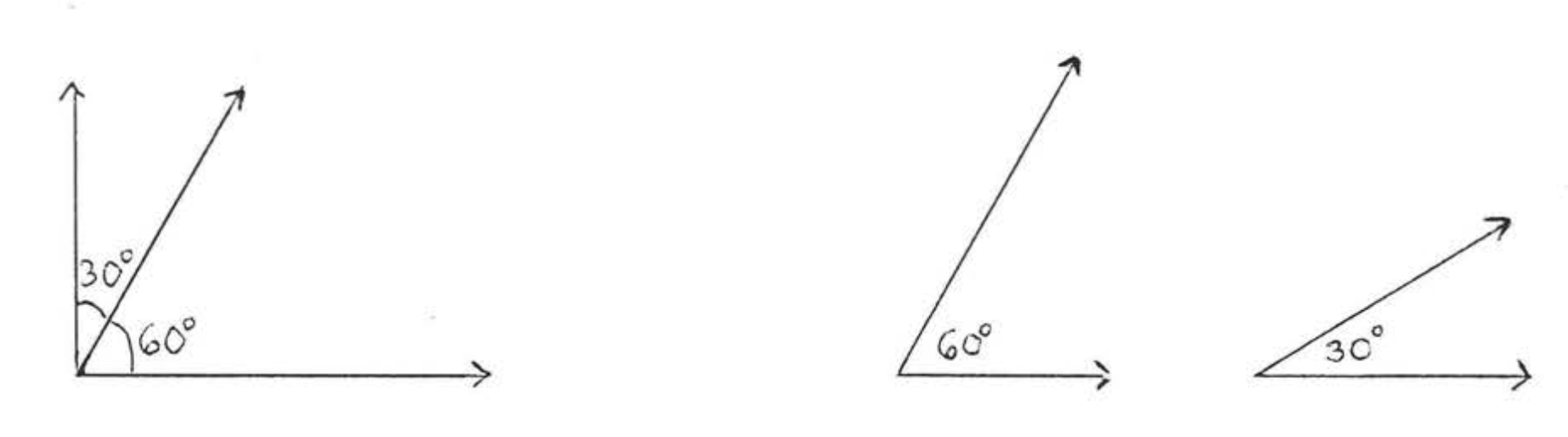

Two angles are called complementary if the sum of their measures is \(90^{\circ}\). Each angle is called the complement of the other. For example, angles of \(60^{\circ}\) and \(30^{\circ}\) are complementary.

Find the complement of a \(40^{\circ}\) angle.

Solution

\(90^{\circ} - 40^{\circ} = 50^{\circ}\).

Answer: \(50^{\circ}\).

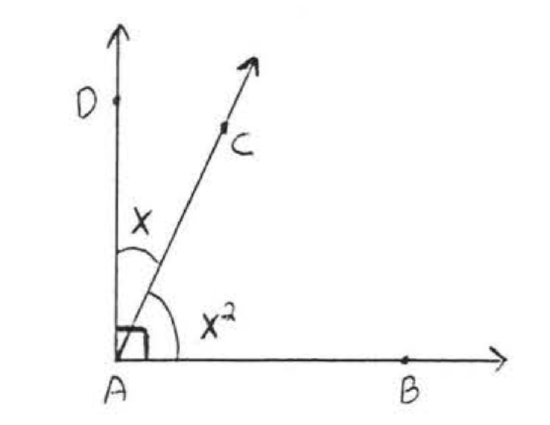

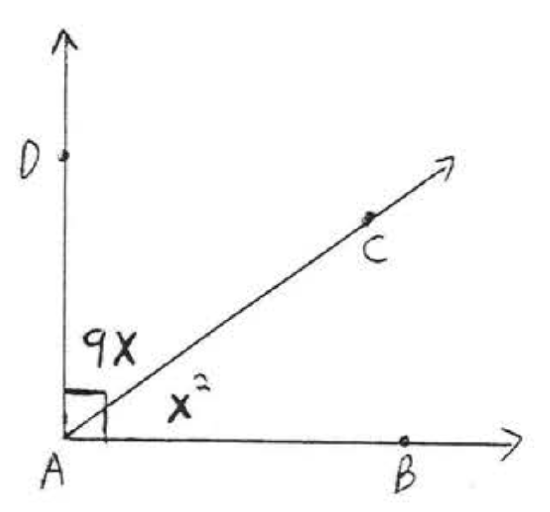

Find \(x\) and the complementary angles:

Solution

Since \(\angle BAD = 90^{\circ}\),

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {x^2 + x} & {90^{\circ}} \\ {x^2 + x - 90} & {0} \\ {(x - 9)(x + 10)} & {0} \end{array}\]

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {x - 9} & = & {0} \\ {x} & = & {9} \end{array}\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \begin{array} {rcl} {x + 10} & = & {0} \\ {x} & = & {-10} \end{array}\]

\(\angle CAD = x = 90^{\circ}\). \(\angle CAD = x = -10^{\circ}.\)

\(\angle BAC = x^2 = 9^2 = 81^{\circ}\).

\(\angle BAC = \angle CAD = 81^{\circ} + 9^{\circ} = 90^{\circ}\).

We reject the answer \(x = -10\) because the measure of an angle is always positive.(In trigonometry, when directed angles are introduced, angles can have negative measure. In this book, however, all angles will be thought of as having positive measure,)

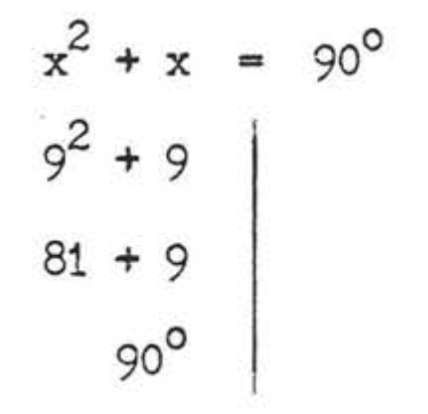

Check, \(x = 9\):

Answer: \(x = 9\), \(\angle CAD = 9^{\circ}\), \(\angle BAC = 81^{\circ}\).

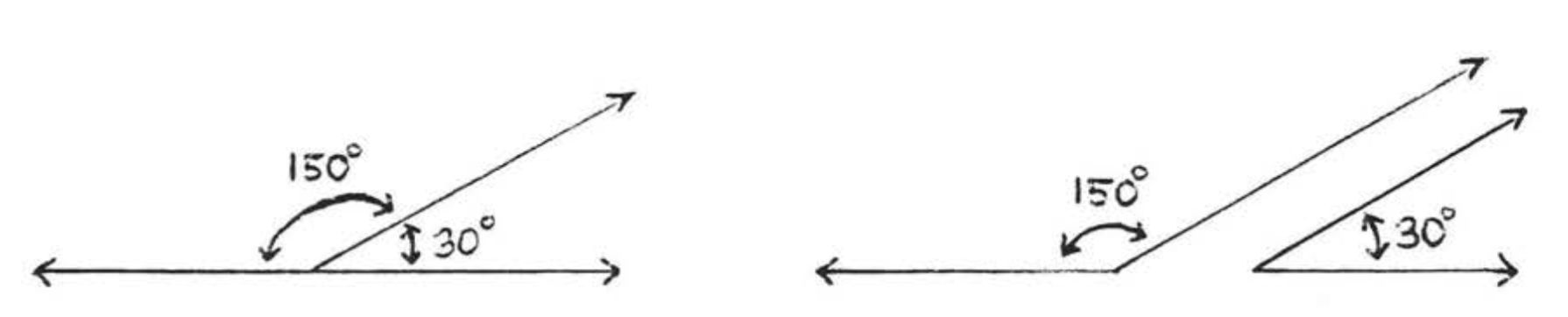

Two angles are called supplementary if the sum of their measures is \(180^{\circ}\). Each angle is called the supplement of the other. For example, angle of \(150^{\circ}\) and \(30^{\circ}\) are supplementary.

Find the supplement of an angle of \(40^{\circ}\).

Solution

\(180^{\circ} - 40^{\circ} = 140^{\circ}\).

Answer: \(140^{\circ}\).

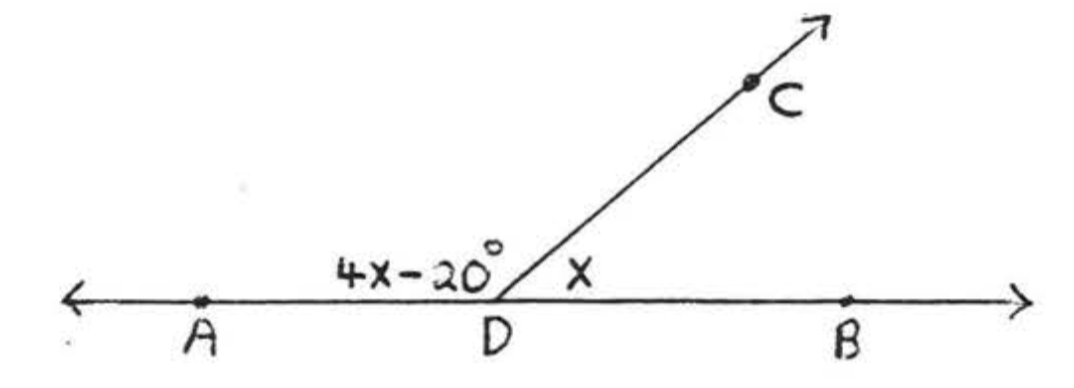

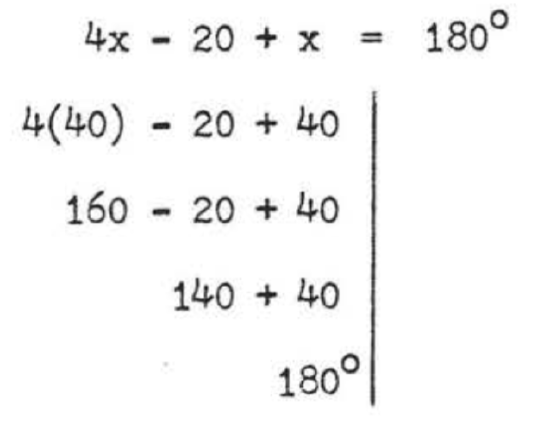

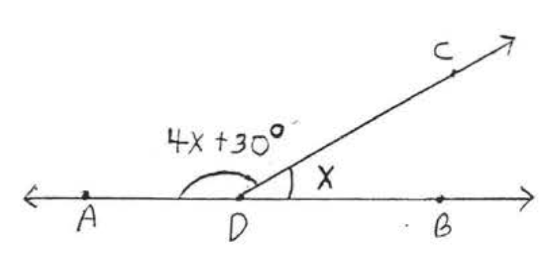

Find \(x\) and the supplementary angles:

Solution

Since \(\angle ADB = 180^{\circ}\),

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {4x - 20 + x} & = & {180^{\circ}} \\ {5x} & = & {180 + 20} \\ {5x} & = & {200} \\ {x} & = & {40} \end{array}\]

\(\angle ADC = 4x - 20 = 4(40) - 20 = 160 - 20 = 140^{\circ}\)

\(\angle BDC = x = 40^{\circ}\),

\(\angle ADC + \angle BDC = 140^{\circ} + 40^{\circ} = 180^{\circ}\).

Check:

Answer

\(x = 40, \angle ADC = 140^{\circ}, \angle BDC = 40^{\circ}\).

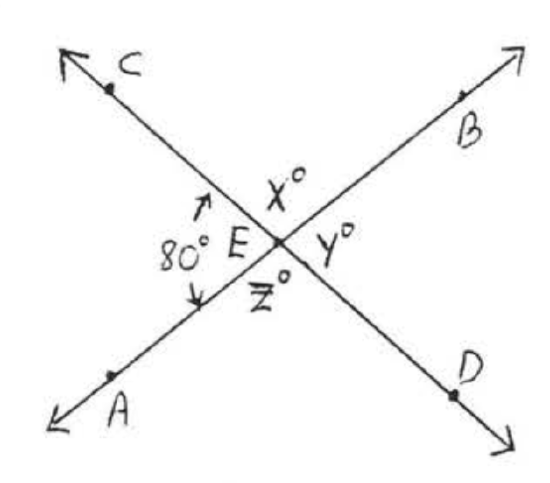

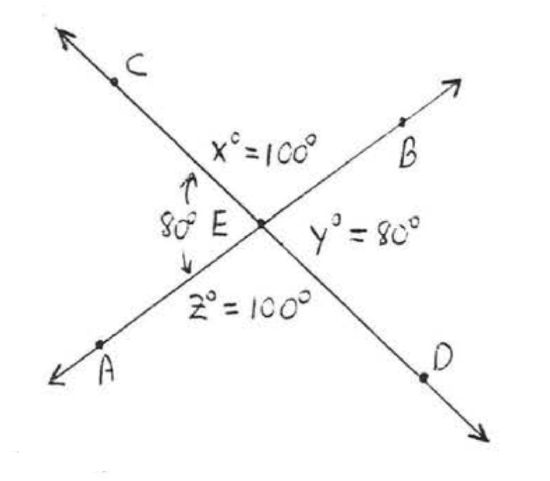

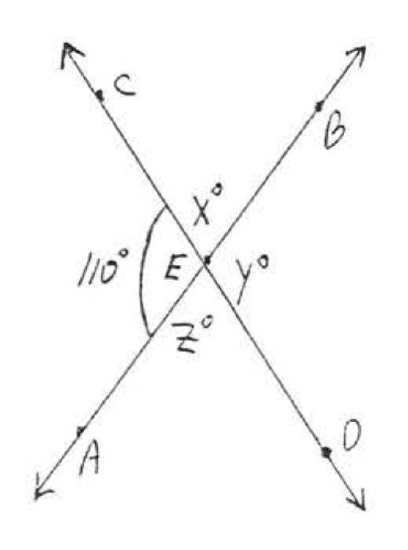

Find \(x, y, z\):

Solution

\(x^{\circ} = 180^{\circ} - 80^{\circ} = 100^{\circ}\) because \(x^{\circ}\) and \(80^{\circ}\) are the measures of supplementary angles.

\[\begin{array} {l} {y^{\circ} = 180^{\circ} - x^{\circ} = 180^{\circ} - 100^{\circ} = 80^{\circ}.} \\ {z^{\circ} = 180^{\circ} - 80^{\circ} = 100^{\circ}.} \end{array}\]

Answer: \(x = 100\), \(y = 80\), \(z = 100\).

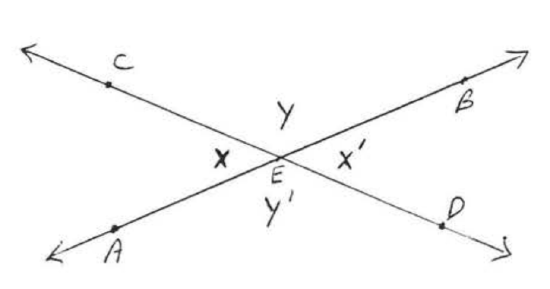

When two lines intersect as in EXAMPLE E, they form two pairs of angles that are opposite to each other called vertical angles, In Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\), \(\angle x\) and \(\angle x'\) are one pair of vertical angles. \(\angle y\) and \(\angle y'\) a.re the other pair of vertical angles, As suggested by Example \(\PageIndex{5}\), \(\angle x = \angle x'\) and \(\angle y = \angle y'\). To see this in general, we can reason as follows: \(\angle x\) is the supplement of \(\angle y\) so \(\angle x = 180^{\circ} - \angle y\). \(\angle x'\) is also the supplement of \(\angle y\) so \(\angle x' = 180 - \angle y\). Therefore \(\angle x = \angle x'\). Similarly, we can show \(\angle y = \angle y'\). Therefore vertical angles are always equal.

We can now use "vertical angles are equal" in solving problems:

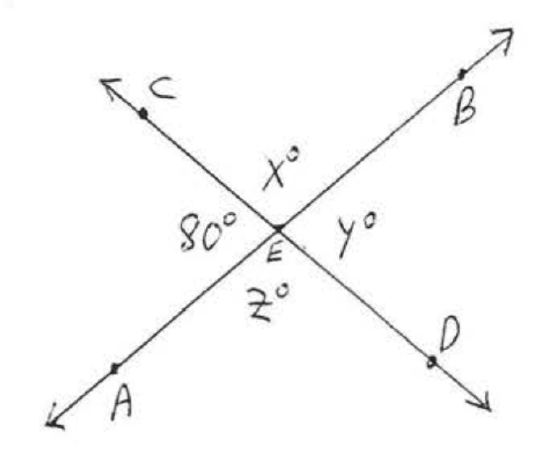

Find \(x, y\), and \(z\):

Solution

\(\angle x = 180^{\circ} - 80^{\circ} = 100^{\circ}\) because \(\angle x\) is the supplement of \(80^{\circ}\).

\(\angle y = 80^{\circ}\) because vertical angles are equal.

\(\angle z = \angle x = 100^{\circ}\) because vertical angles are equal.

Answer: \(x = 100\), \(y = 80\), \(z = 100\).

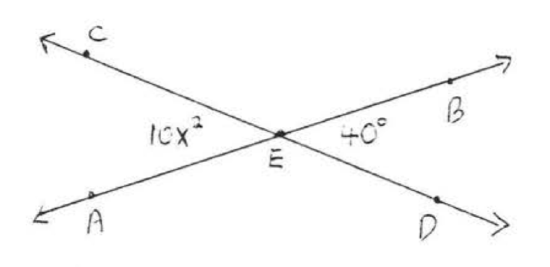

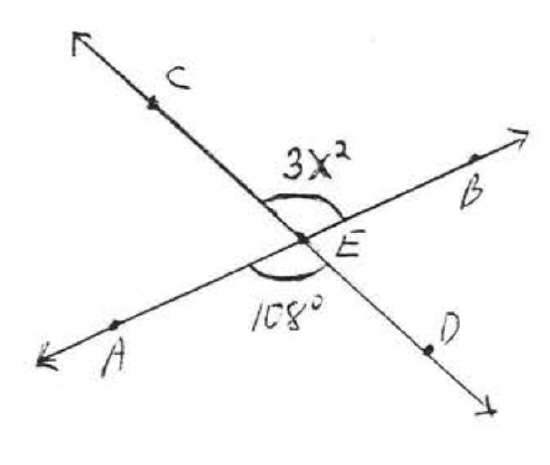

Find \(x\):

Solution

Since vertical angles are equal, \(10x^2 = 40^{\circ}\).

\(\begin{array} {rclcrcl} {\text{Method 1:} \ \ \ \ \ \ 10x^2} & = & {40} & \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ & {\text{Method 2:} \ \ \ \ \ \ 10x^2} & = & {40} \\ {10x^2 - 40} & = & {0} & \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ & {\dfrac{10x^2}{10}} & = & {\dfrac{40}{10}} \\ {(10)(x^2 - 4)} & = & {0} & \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ & {x^2} & = & {4} \\ {x^2 - 4} & = & {0} & \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ & {x} & = & {\pm 2} \\ {(x + 2)(x - 2)} & = & {0} & \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ & {} & & {} \end{array}\)

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {x + 2} & = & {0} \\ {x} & = & {-2} \end{array}\) \(\begin{array} {rcl} {x - 2} & = & {0} \\ {x} & = & {2} \end{array}\)

If \(x = 2\) then \(\angle AEC = 10x^2 = 10(2)^2 = 10(4) = 40^{\circ}\).

If \(x = -2\) then \(\angle AEC = 10x^2 = 10(-2)^2 = 10(4) = 40^{\circ}\).

We accept the solution \(x =-2\) even though \(x\) is negative because the value of the angle \(10x^2\) is still positive.

Check:

Answer: \(x = 2\) or \(x = -2\).

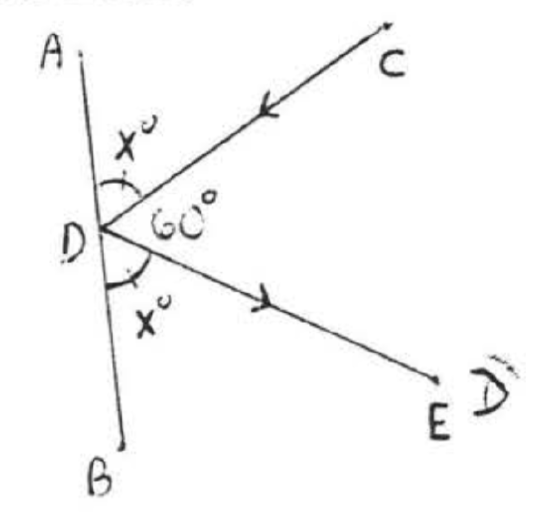

In the diagram, \(AB\) represents a mirror, \(CD\) represents a ray of light approaching the mirror from \(C\), and \(E\) represents the eye of a person observing the ray as it is reflected from the mirror at \(D\). According to a law of physics, \(\angle CDA\), called the angle of incidence, equals \(\angle EDB\), called the angle of reflection. If \(\angle CDE = 60^{\circ}\), how much is the angle of incidence?

Solution

Let \(\x^{\circ} = \angle CDA = \angle EDB\).

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {x + x + 60} & = & {180} \\ {2x + 60} & = & {180} \\ {2x} & = & {120} \\ {x} & = & {60} \end{array}\]

Answer: \(60^{\circ}\)

The statement "vertical angles are always equal" is an example of a theorem. A theorem is a statement which we can prove to be true, A proof is a process of reasoning which uses statements already known to be true to show the truth of a new statement, A example of a proof is the discussion preceding the statement "vertical angles are always equal." We used facts about supplementary angles that were already known to establish the new statement, that "vertical angles are always equal."

Ideally we would like to prove all statements in mathematics which we think are true. However before we can begin proving anything we need some true statements with which to start. Such statements should be so self-evident as not to require proofs themselves, A statement of this kind, which we assume to be true without proof, is called a postulate or an axiom. An example of a postulate is the assumption that all angles can be measured in degrees. This was used without actually being stated in our proof that "vertical angles are always equal,"

Theorems, proofs, and postulates constitute the heart of mathematics and we will encounter many more of them as we continue our study of geometry.

Problems

1. Find the complement of an angle of

- \(37^{\circ}\)

- \(45^{\circ}\)

- \(53^{\circ}\)

- \(60^{\circ}\)

2. Find the complement of an angle of

- \(30^{\circ}\)

- \(40^{\circ}\)

- \(50^{\circ}\)

- \(81^{\circ}\)

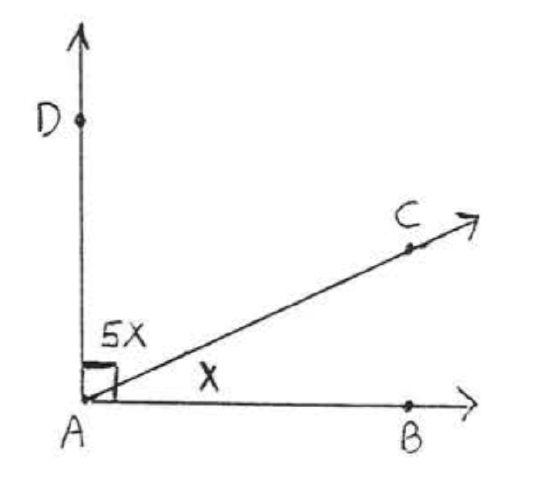

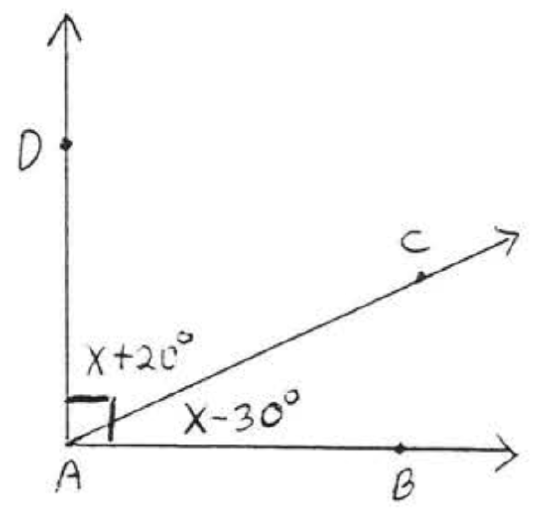

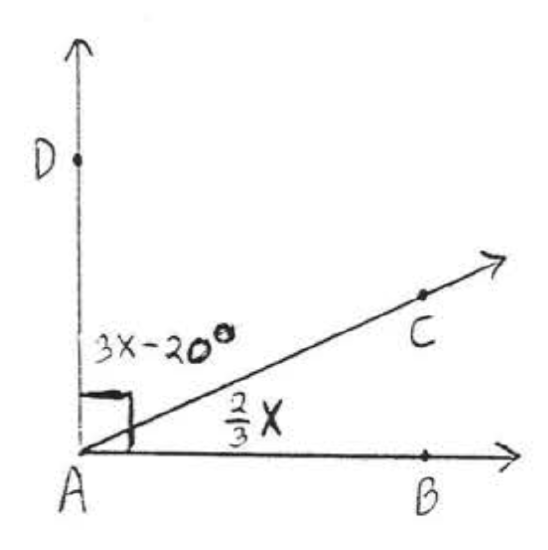

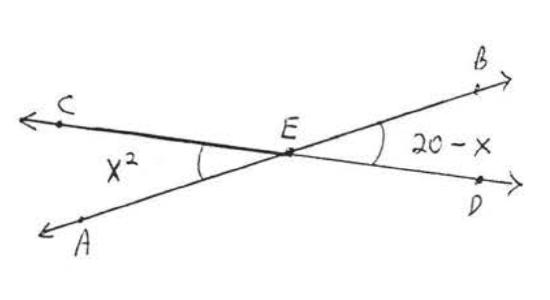

3 - 6. Find \(x\) and the complementary angles:

3.  4.

4.

5.  6.

6.

7. Find the supplement of an angle of

- \(30^{\circ}\)

- \(37^{\circ}\)

- \(90^{\circ}\)

- \(120^{\circ}\)

8. Find the supplement of an angle of

- \(45^{\circ}\)

- \(52^{\circ}\)

- \(85^{\circ}\)

- \(135^{\circ}\)

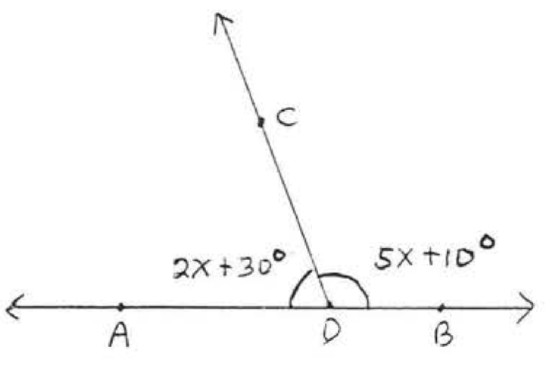

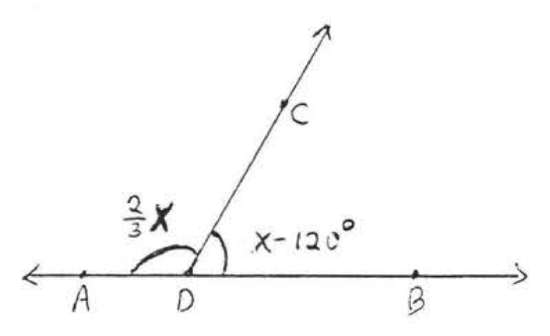

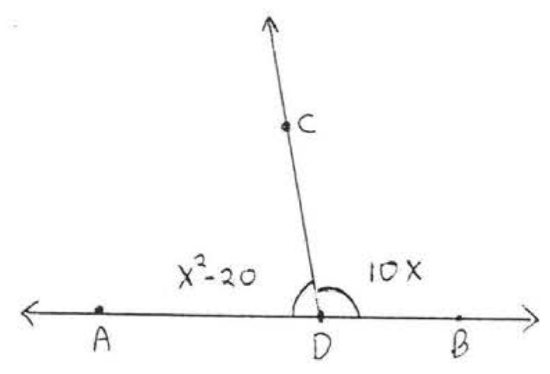

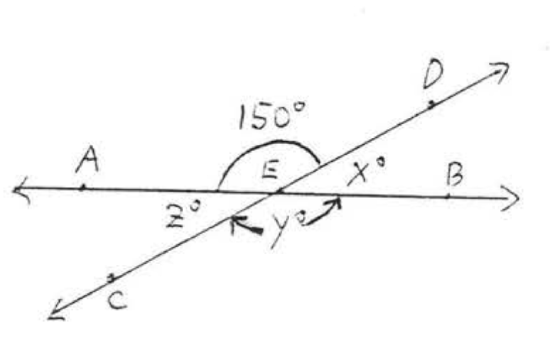

9 - 14. Find \(x\) and the supplementary angles:

9.  10.

10.

11.  12.

12.

13.  14.

14.

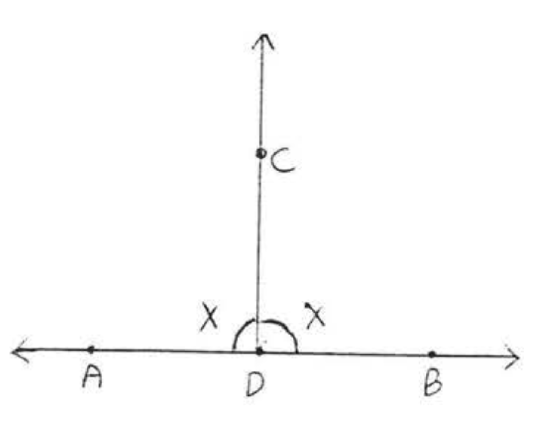

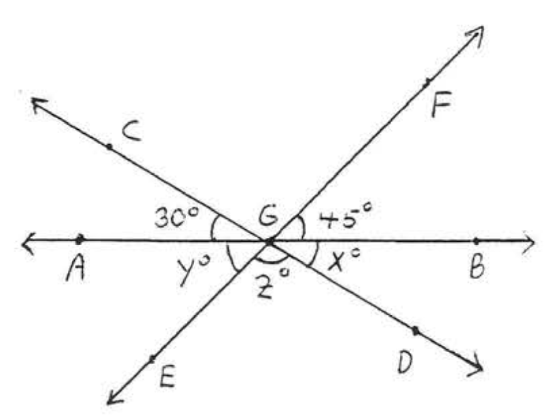

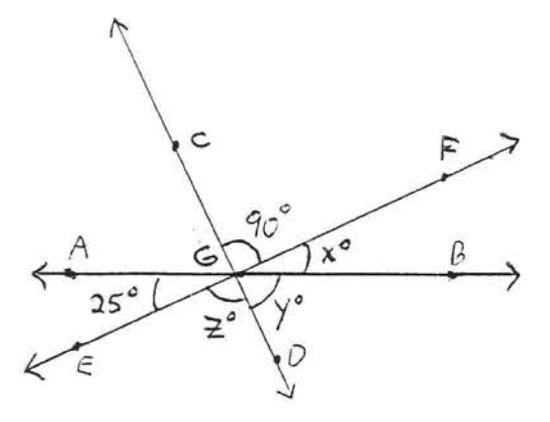

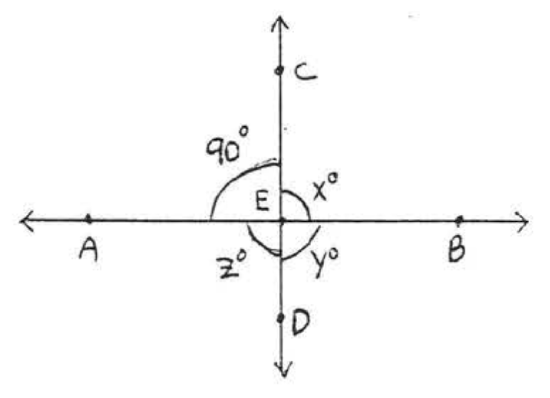

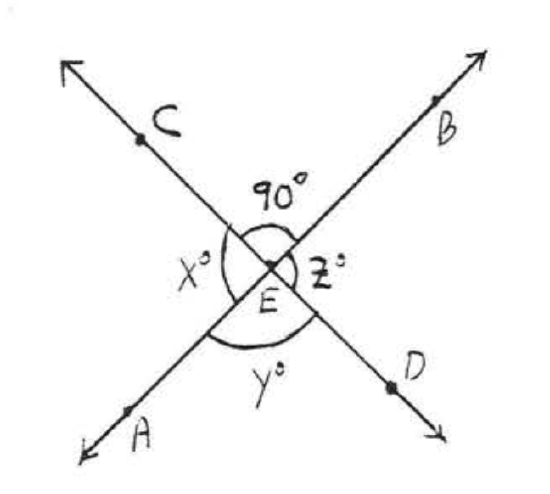

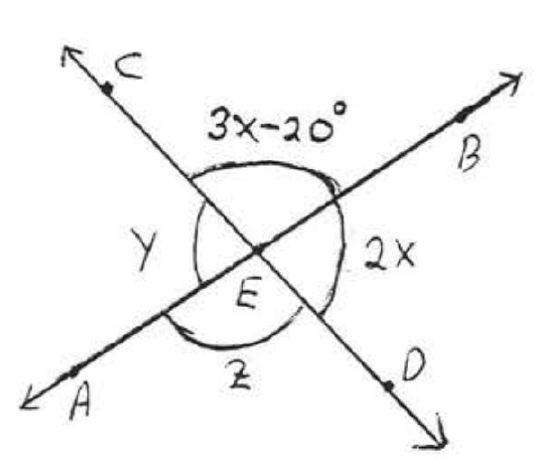

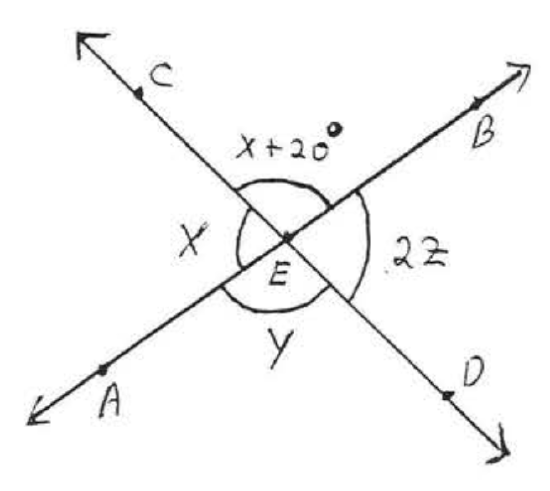

15 - 22. Find \(x, y\), and \(z\):

15.  16.

16.

17.  18.

18.

19.  20.

20.

21.  22.

22.

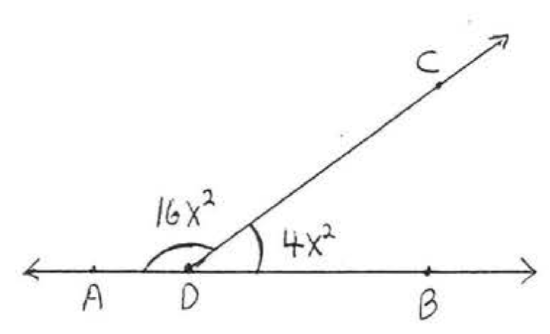

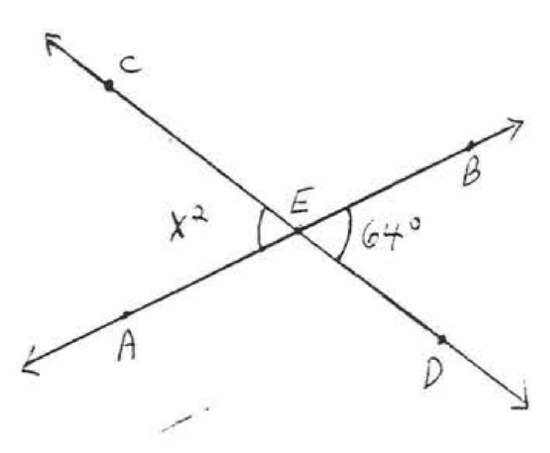

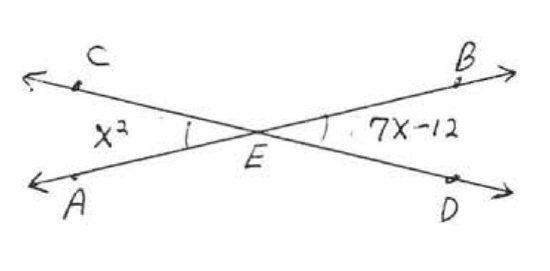

23 - 26. Find \(x\):

23.  24.

24.

25.  26.

26.

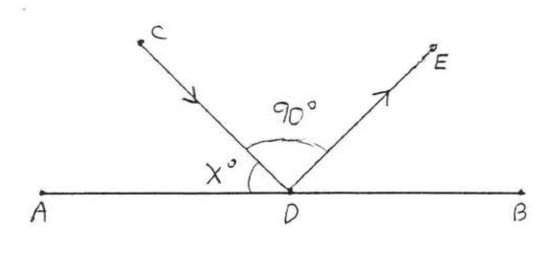

27. Find the angle of incidence, \(\angle CDA\):

28. Find \(x\) if the angle of incidence is \(40^{\circ}\):