1.4: Parallel Lines

- Page ID

- 34120

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

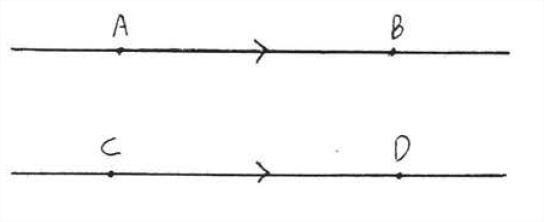

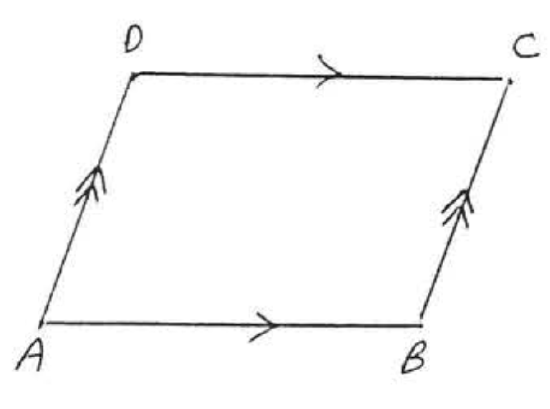

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Two lines are parallel if they do not meet, no matter how far they are extended. The symbol for parallel is \(||\). In Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), \(\stackrel{\leftrightarrow}{A B}\) \(||\) \(\stackrel{\leftrightarrow}{C D}\). The arrow marks are used to indicate the lines are parallel.

We make the following assumption about parallel lines, called the parallel postulate.

The probabilities assigned to events by a distribution function on a sample space are given by

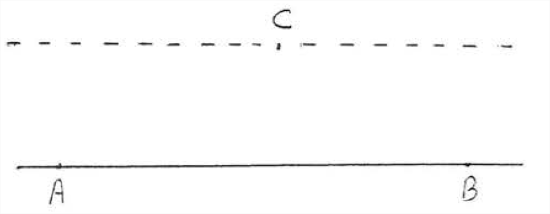

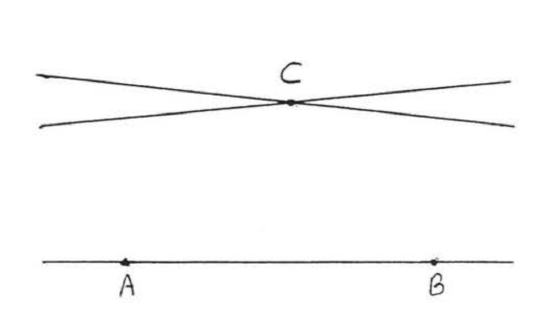

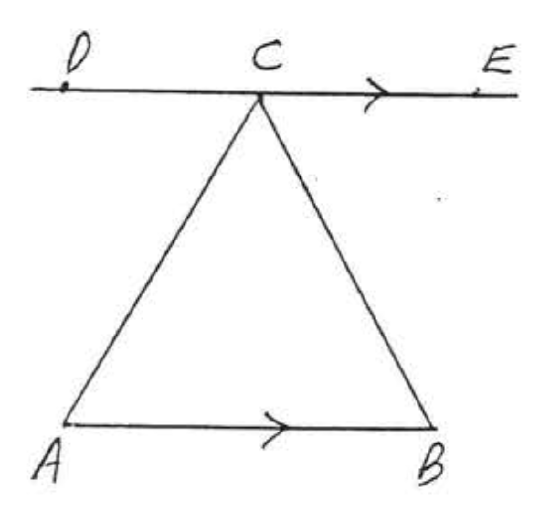

Through a point not on a given line one and only one line can be drawn parallel to the given line. So in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), there is exactly one line that can be drawn through \(C\) that is parallel to \(\overleftarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\).

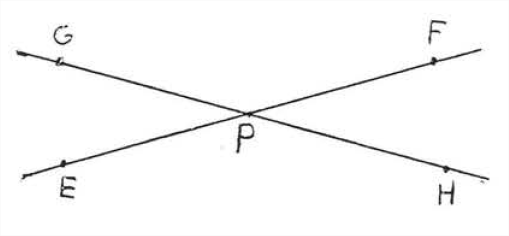

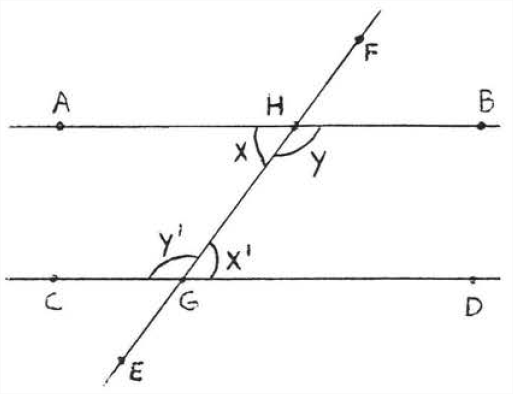

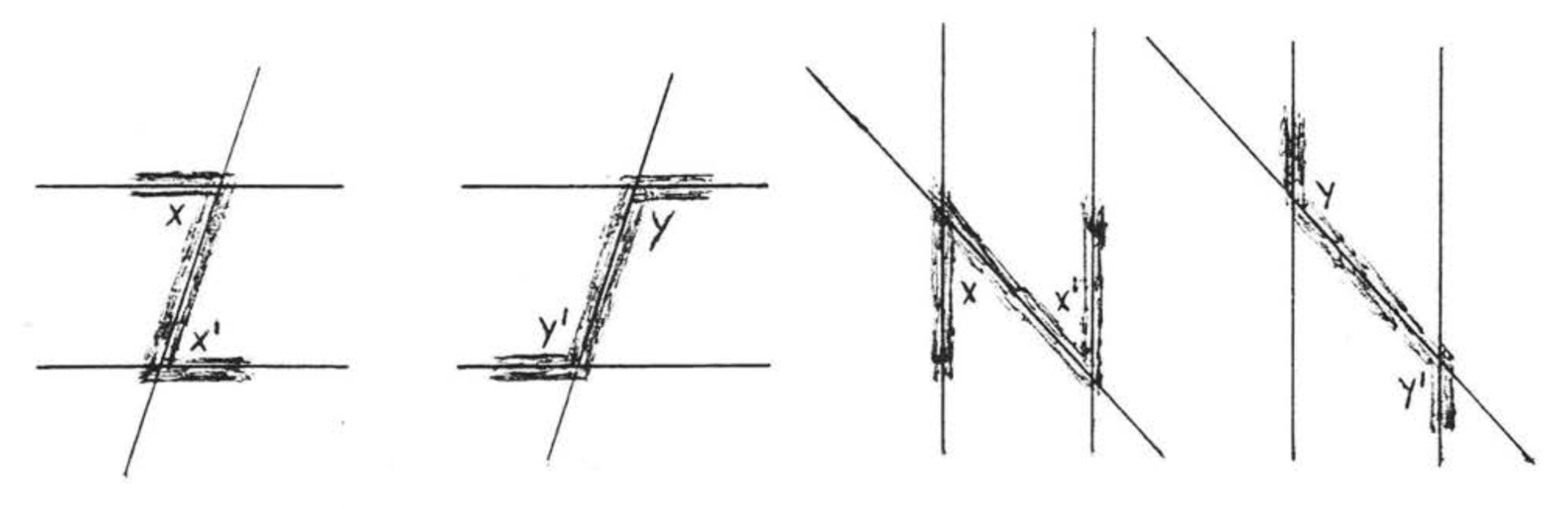

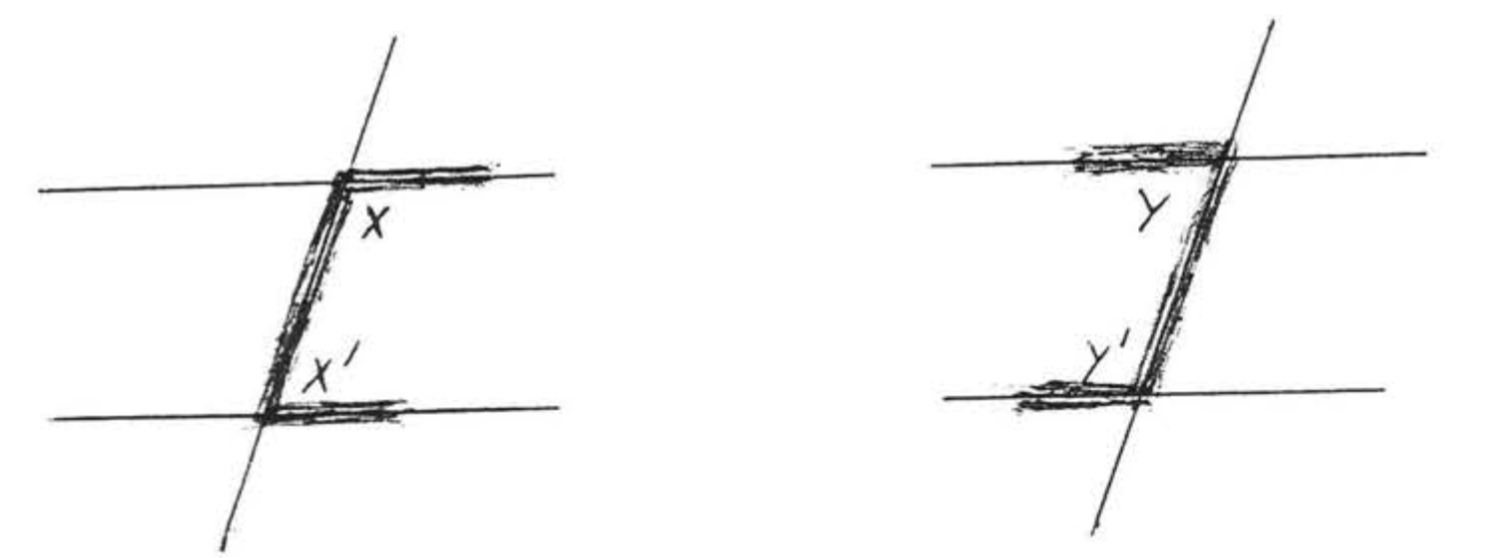

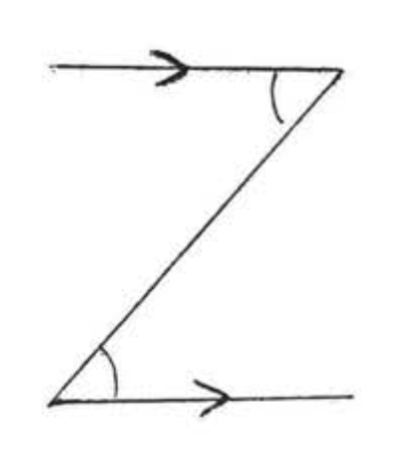

A transversal is a line that intersects two other lines at two distinct points. In Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\), \(\overleftrightarrow{EF}\) is a transversal. \(\angle x\) and \(\angle x^{\prime}\) are called alternate interior angles of lines \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\). The word "alternate," here, means that the angles are on different sides of the transversal, one angle formed with \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and the other formed with \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\). The word "interior" means that they are between the two lines. Notice that they form the letter "\(Z\)." (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). \(\angle y\) and \(\angle y^{\prime}\) are also alternate interior angles. They also form a "\(Z\)" though It is stretched out and backwards. Viewed from the side, the letter "\(Z\)" may also look like an "\(N\)."

Alternate interior angles are important because of the following theorem:

If two lines are parallel then their alternate interior angles are equal, If the alternate interior angles of two lines are equal then the lines must 'oe parallel,

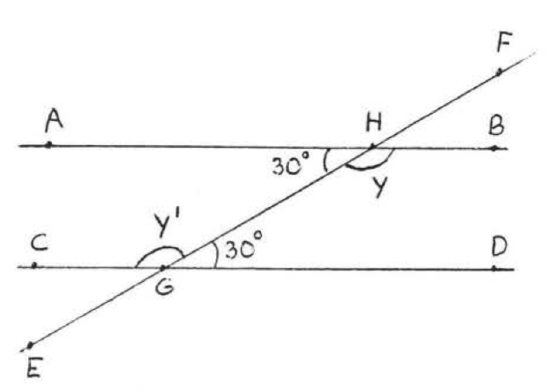

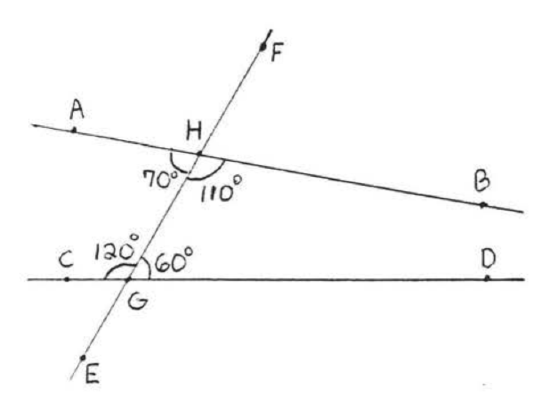

In Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) must be parallel to \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\) because the alternate interior angles are both \(30^{\circ}\). Notice that the other pair of alternate interior angles, \(\angle y\) and \(\angle y'\), are also equal. They are both \(150^{\circ}\). In Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\), the lines are not parallel and none of the alternate interior angles are equal.

The Proof of Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\) is complicated and will be deferred to the appendix.

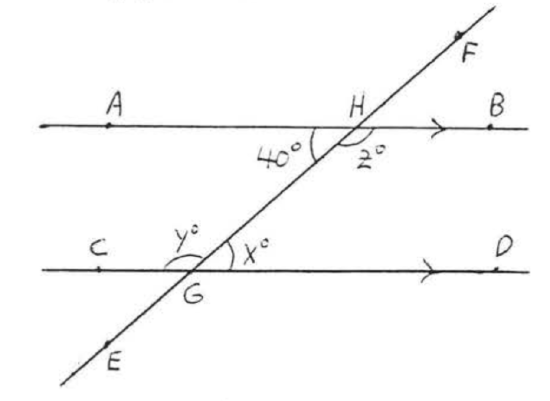

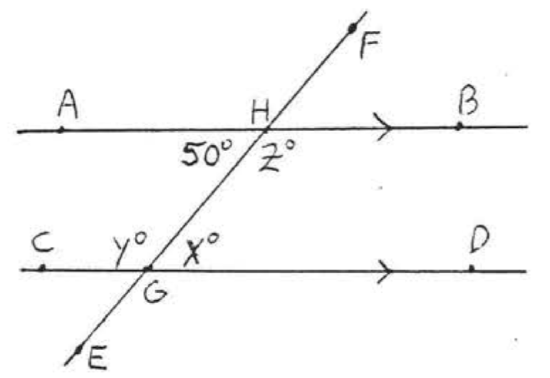

Find \(x, y\) and \(z\):

Solution

\(\overleftrightarrow{AB} || \overleftrightarrow{CD}\) since the arrows indicate parallel lines. \(x^{\circ} = 40^{\circ}\) because alternate interior angles of parallel lines are equal. \(y^{\circ} = z^{\circ} = 180^{\circ} - 40^{\circ} = 140^{\circ}\).

Answer: \(x = 40, y = 140, z = 140\).

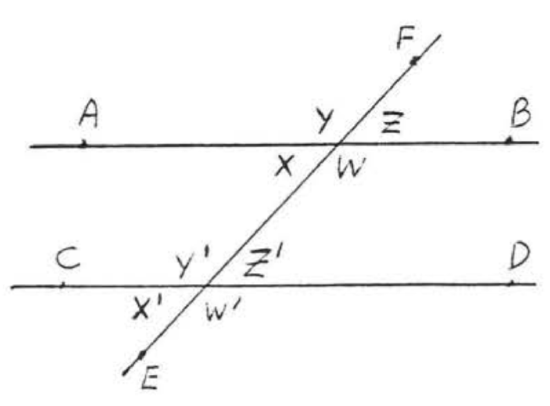

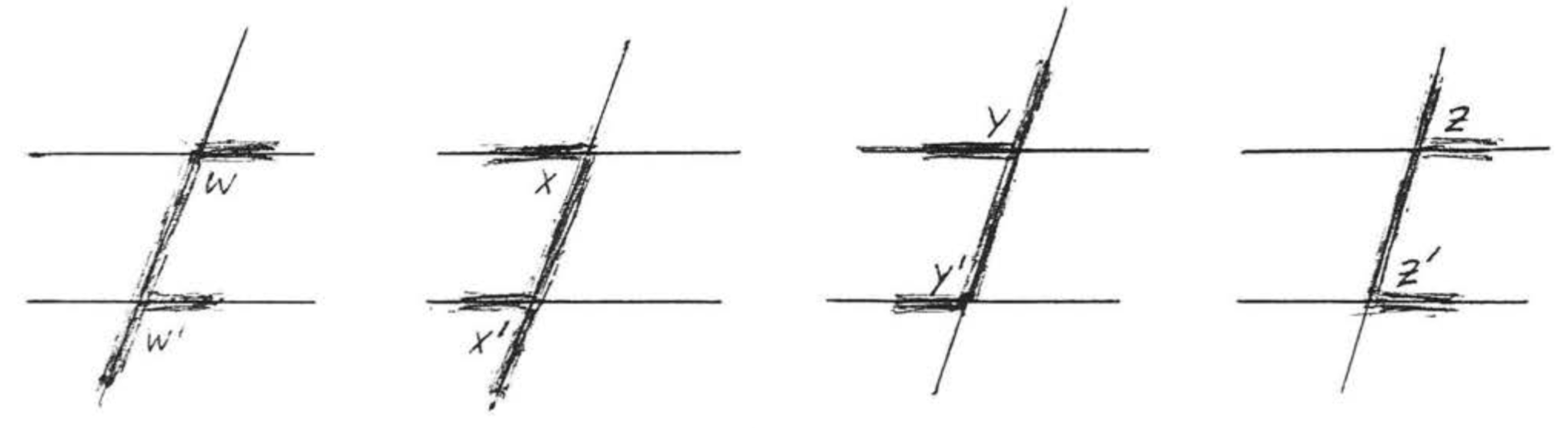

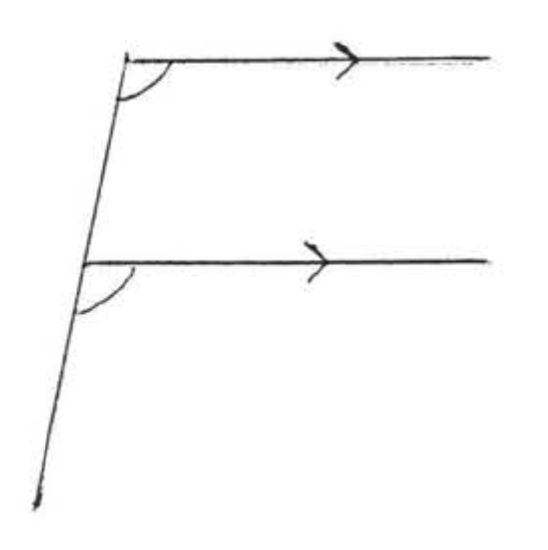

Corresponding angles of two lines are two angles which are on the same side of the two lines and the same side of the transversal, In Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\), \(\angle w\) and \(\angle w'\) are corresponding angles of lines \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\). They form the letter "\(F\)." \(\angle x\) and \(\angle x'\), \(\angle y\) and \(\angle y'\), and \(\angle z\) and \(\angle z'\) are other pairs of corresponding angles of \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\). They all form the letter "\(F\)", though it might be a backwards or upside down "\(F\)" (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)).

Corresponding angles are important because of the following theorem:

If two lines are parallel then their corresponding angles are equal. If the corresponding angles of two lines are equal then the lines must be parallel.

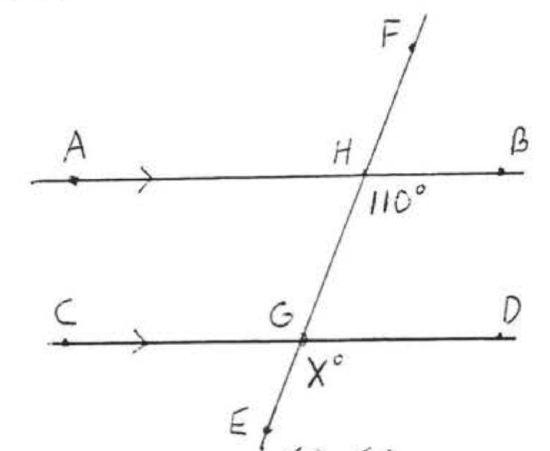

Find \(x\):

Solution

The arrow indicate \(\overleftrightarrow{AB} || \overleftrightarrow{CD}\). Therefore \(x^{\circ} = 110^{\circ}\) because \(x^{\circ}\) and \(110^{\circ}\) are the measures of corresponding angles of the parallel lines \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\).

Answer: \(x = 110\).

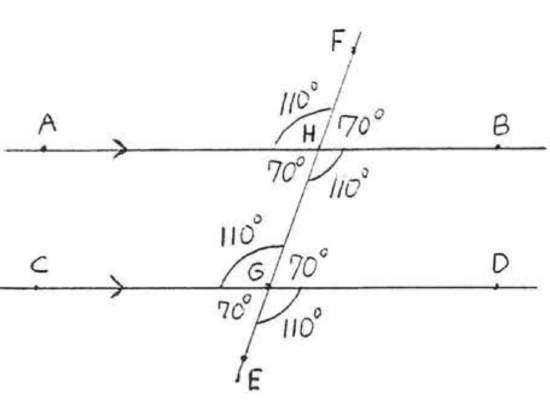

Notice that we can now find all the other angles in Example \(PageIndex{2}\). Each one is either supplementary to one of the \(110^{\circ}\) angles or forms equal vertical angles with one of them (Figure \(PageIndex{10}\)). Therefore all the corresponding angles are equal, Also each pair of alternate interior angles is equal. It is not hard to see that if just one pair of corresponding angles or one pair of alternate interior angles are equal then so are all other pairs of corresponding and alternate interior angles.

Proof of Theorem \(\PageIndex{2}\): The corresponding angles will be equal if the alternate interior angles are equal and vice versa. Therefore Theorem \(\PageIndex{2}\) follows directly from Therorem \(\PageIndex{1}\).

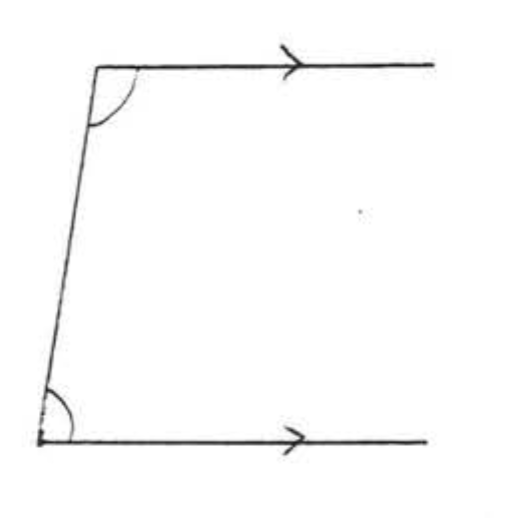

In Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\), \(\angle x\) and \(\angle x'\) are called interior angles on the same side of the transversal.(In some textbooks, interior angles on the same sdie of the transversal are called cointerior angles.) \(\angle y\) and \(\angle y'\) are also interior angles on the same side of the transversal, Notice that each pair of angles forms the letter "\(C\)." Compare Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) with Figure 10 and also with Example \(\PageIndex{1}\), The following theorem is then apparent:

If two lines are parallel then the interior angles on the same side of the transversal are supplementary (they add uP to \(180^{\circ}\)). If the interior angles of two lines on the same side of the transversal are supplementary then the lines must be parallel.

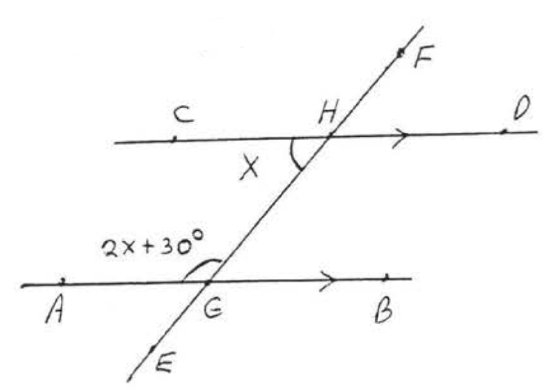

Find \(x\) and the marked angles:

Solution

The lines are parallel so by Theorem \(\PageIndex{3}\) the two labelled angles must be supplementary.

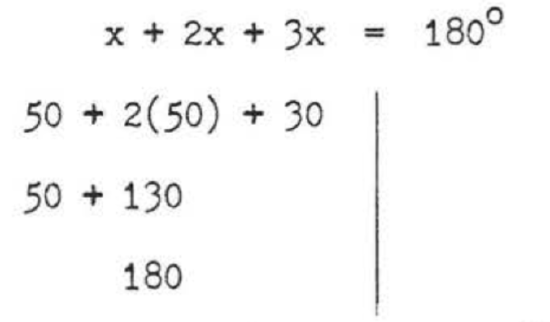

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {x + 2x + 30} & = & {180} \\ {3x + 30} & = & {180} \\ {3x} & = & {180 - 30} \\ {3x} & = & {150} \\ {x} & = & {50} \end{array}\]

\(\angle CHG = x = 50^{\circ}\)

\(\angle AGH = 2x + 30 = 2(50) + 30 = 100 + 30 = 130^{\circ}\).

Check:

Answer: \(x = 50\), \(\angle CHG = 50^{\circ}\), \(\angle AGHa = 130^{\circ}\).

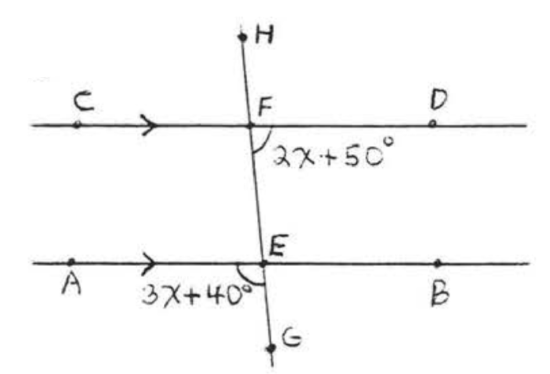

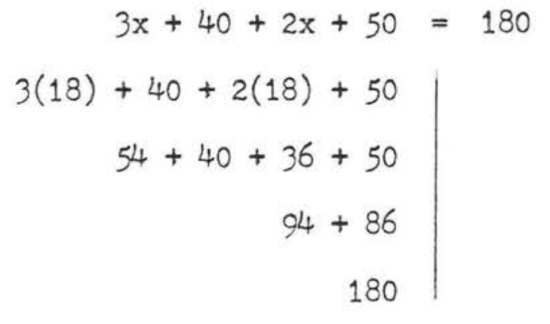

Find \(x\) and the marked angles:

Solution

\(\angle BEF = 3x + 40^{\circ}\) because vertical angles are equal. \(\angle BEF\) and \(\angle DFE\) are interior angles on the same side of the transversal, and therefore are supplementary because the lines are parallel.

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {3x + 40 + 2x + 50} & = & {180} \\ {5x + 90} & = & {180} \\ {5x} & = & {180 - 90} \\ {5x} & = & {90} \\ {x} & = & {18} \end{array}\]

\(\angle AEC = 3x + 40 = 3(18) + 40 = 54 + 40 = 94^{\circ}\)

\(\angle DFE = 2x + 50 = 2(18) + 50 = 36 + 50 = 86^{\circ}\)

Check:

Answer: \(x = 18\), \(\angle AEG = 94^{\circ}\), \(\angle DFE = 86^{\circ}\).

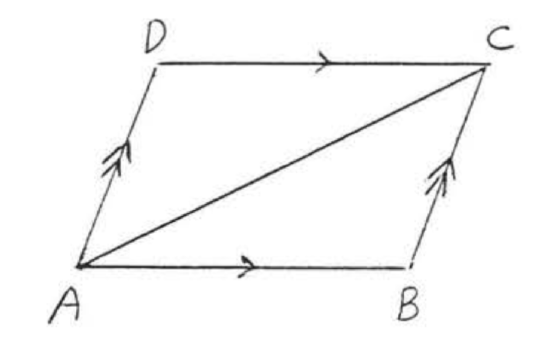

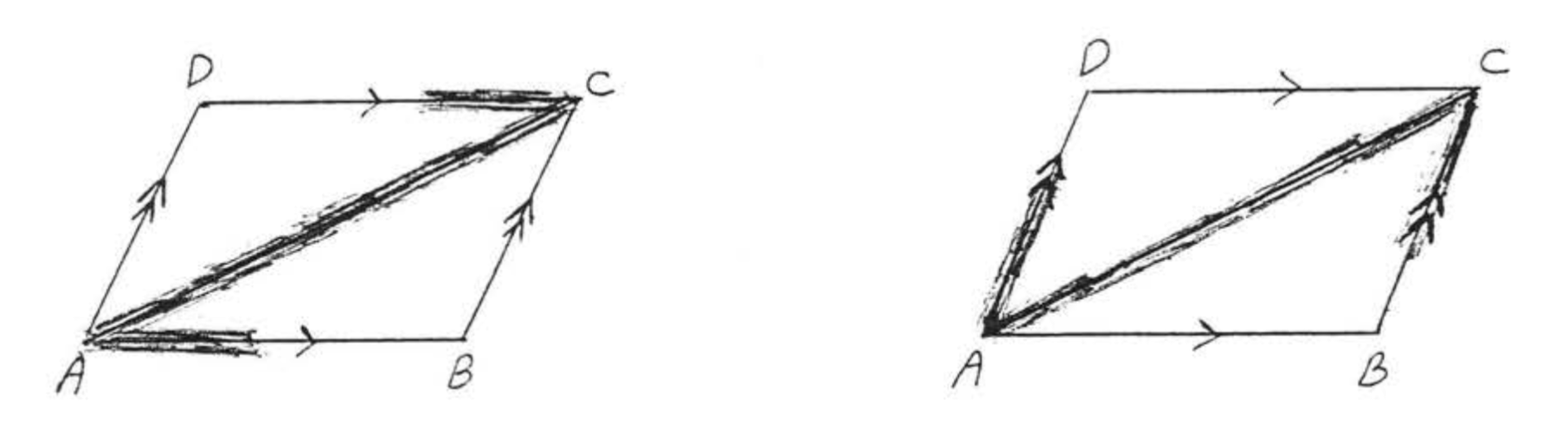

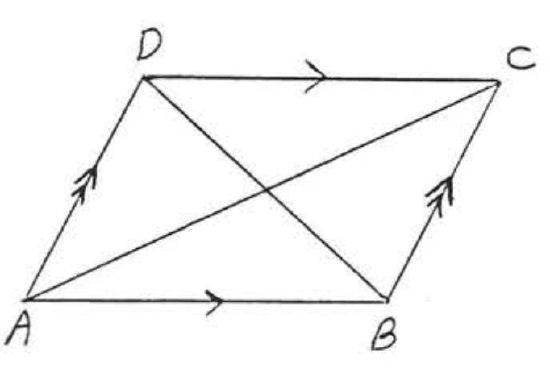

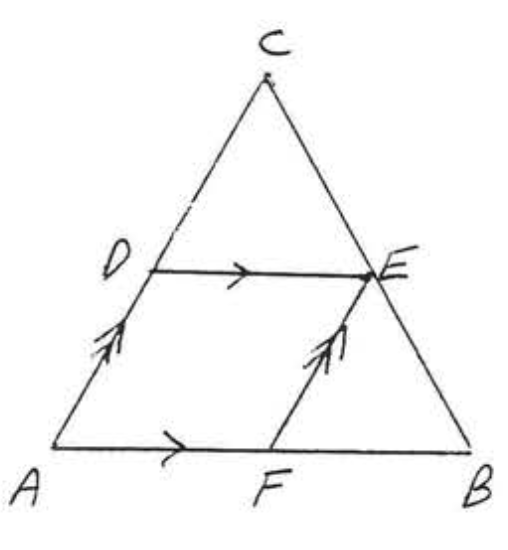

List all pairs of alternate interior angles in the diagram, (The single arrow indicates \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) is parallel to \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\) and the double arrow indicates \(\overleftrightarrow{AD}\) is parallel to \(\overleftrightarrow{BC}\).

Solution

We see if a letter \(Z\) or \(N\) can be formed using the line segments in the diagram (Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)),

Answer: \(\angle DCA\) and \(\angle CAB\) are alternate interior angles of lines \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\). \(\angle DAC\) and \(\angle ACB\) are alternate interior angles of lines \(\overleftrightarrow{AD}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{BC}\)

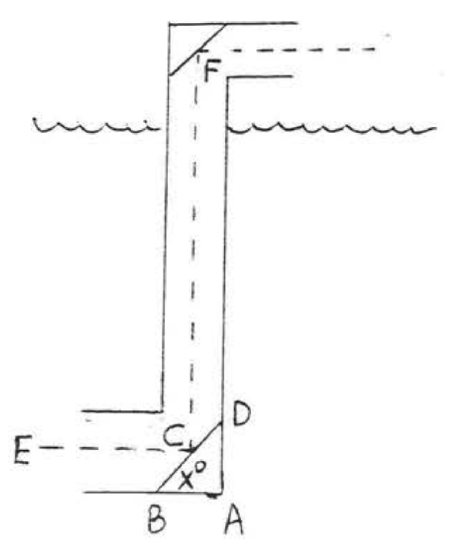

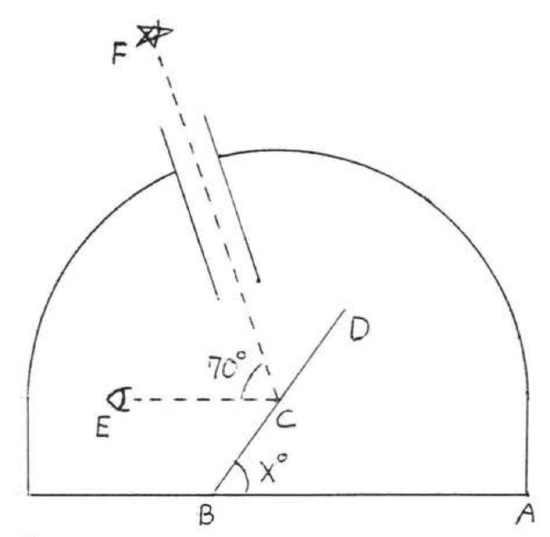

A telescope is pointed at a star \(70^{\circ}\) above the horizon, What angle \(x^{\circ}\) must the mirror \(BD\) make with the horizontal so that the star can be seen in the eyepiece \(E\)?

Solution

\(x^{\circ} = \angle BCE\) because they are alternate interior angles of parallel lines \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{CE}\). \(\angle DCF = \angle BCE = x^{\circ}\) because the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection. Therefore

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {x + 70 + x} & = & {180} \\ {2x + 70} & = & {180} \\ {2x} & = & {110} \\ {x} & = & {55} \end{array}\]

Answer: \(55^{\circ}\)

SUMMARY

Alternate interior angles of paralle lines are equal. They form the letter "\(Z\)."

Corresponding angles of parallel lines are equal. They form the letter "\(F\)."

Interior angles on the same sides of the transversal of parallel lines are supplementary. They form the letter "\(G\)."

The parallel postulate given earlier in this section is the equivalent of the fifth postulate of Euclid's Elements. Euclid was correct in assuming it as a postulate rather than trying to prove it as a theorem, However this did not become clear to the mathematical world until the nineteenth century, 2200 years later, In the interim, scores of prominent mathematicians attempted unsuccessfully to give a satisfactory proof of the parallel postulate. They felt that it was not as self-evident as a postulate should be, and that it required some formal justification,

In 1826, N, I, Lobachevsky, a Russian mathematician, presented a system of geometry based on the assumption that through a given point more than one straight line can be drawn parallel to a given line (Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)). In 1854, the German mathematician Georg Bernhard Riemann proFosed a system of geometriJ in which there are no parallel lines at all, A gecmetry in which the parallel postulate has been replaced by some other postulate is called a non-Euclidean geometry. The existence of these geometries shows that the parallel postulate need not necessarily be true. Indeed Einstein used the geometry of Riemann as the basis for his theory of relativity.

Of course our original parallel postulate makes the most sense for ordinary applications, and we use it throughout this book, However, for applications where great distances are involved, such as in astronomy, it may well be that a non-Euclidean geometry gives a better approximation of physical reality.

Problems

For each of the following, state the theorem(s) used in obtaining your answer (for example, "alternate interior angles of parallel lines are equal"). Lines marked with the same arrow are assumed to be parallel,

1 - 2. Find \(x, y\), and \(z\):

1.  2.

2.

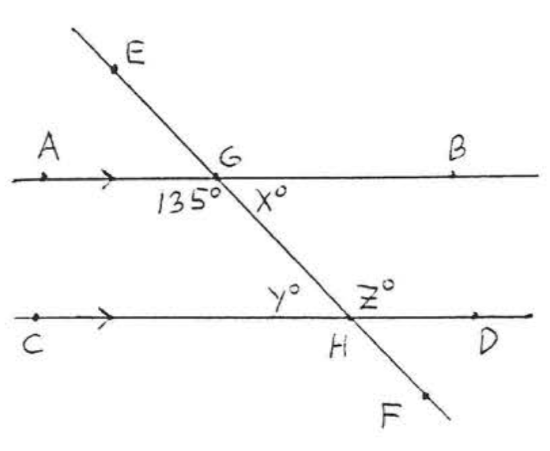

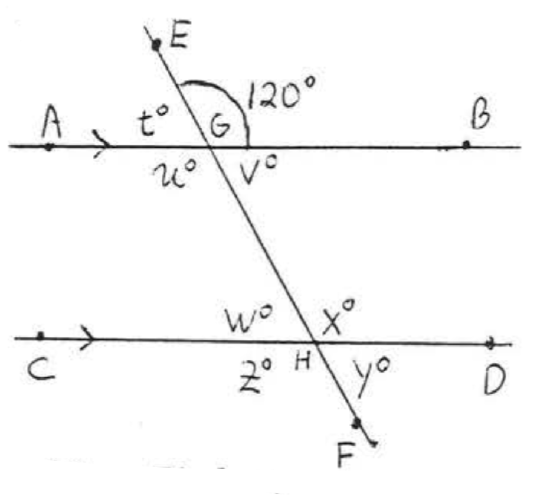

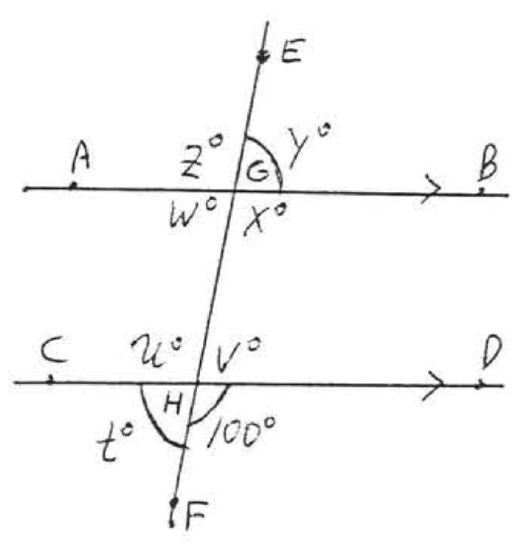

3 - 4. Find \(t\), \(u\), \(v\), \(w\), \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\):

3.  4.

4.

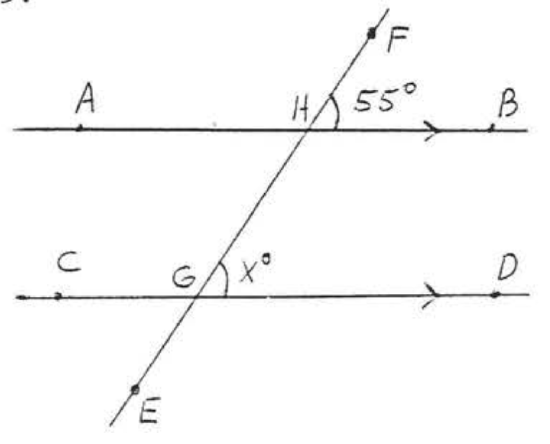

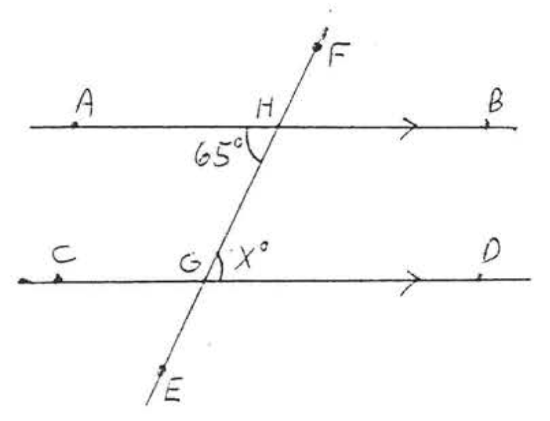

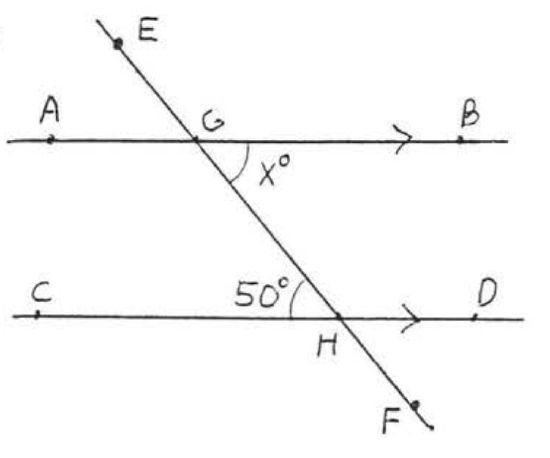

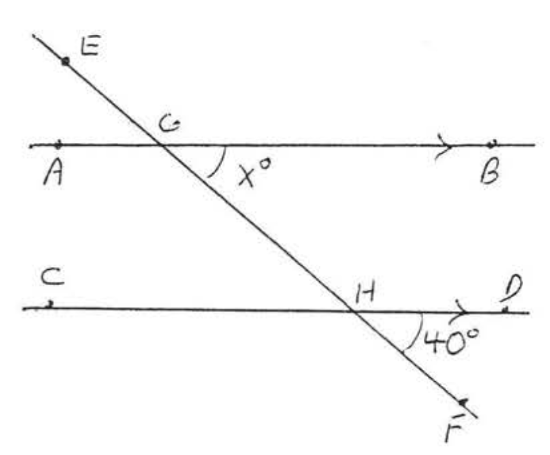

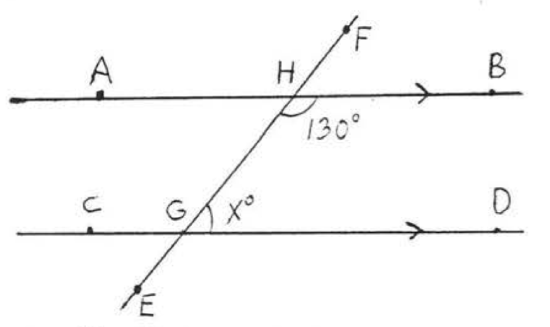

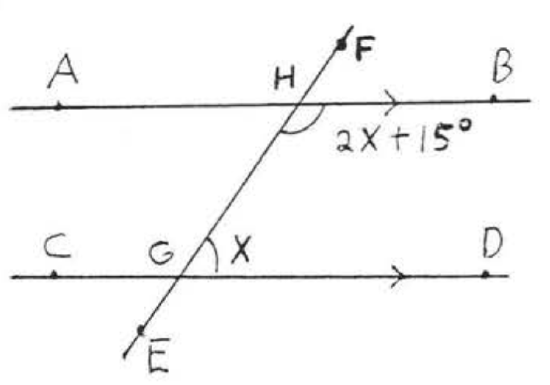

5 - 10. Find \(x\):

5.  6.

6.

7.  8.

8.

9.  10.

10.

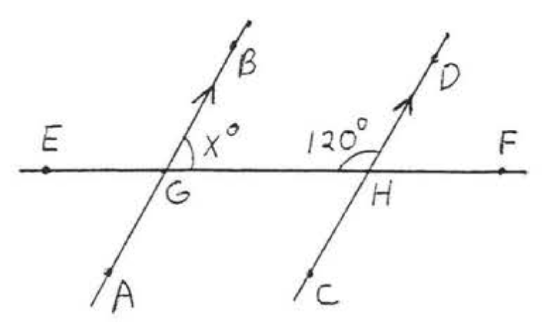

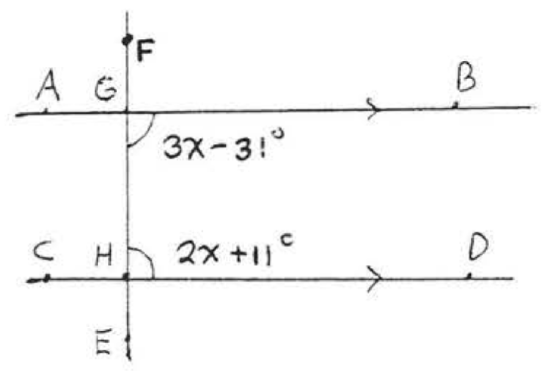

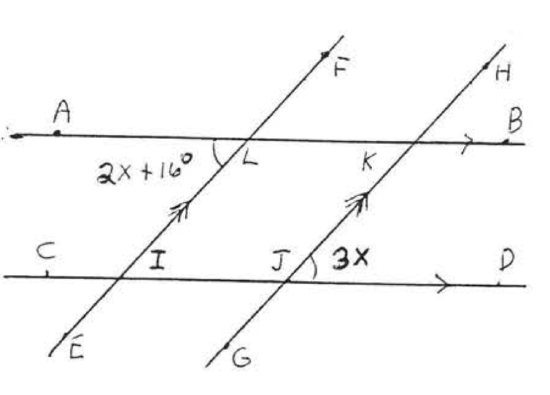

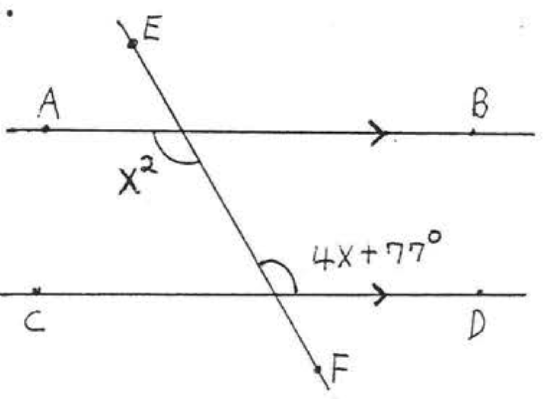

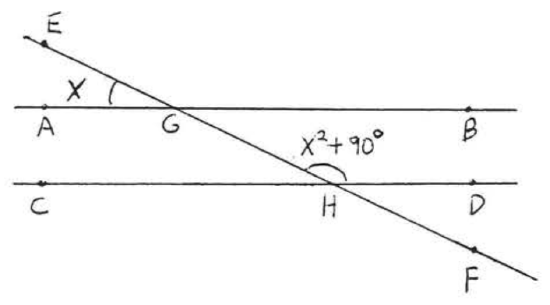

11 - 18. Find \(x\) and the marked angles:

11.  12.

12.

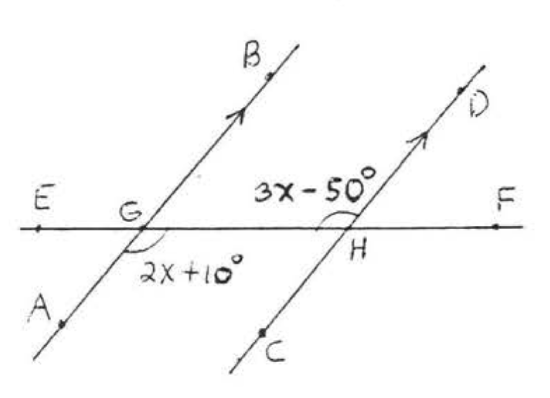

13.  14.

14.

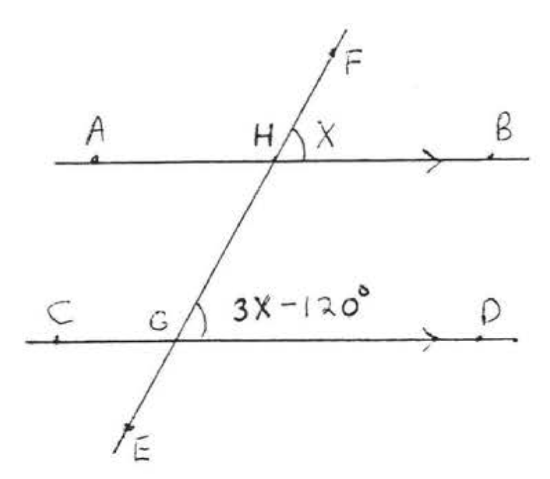

15.  16.

16.

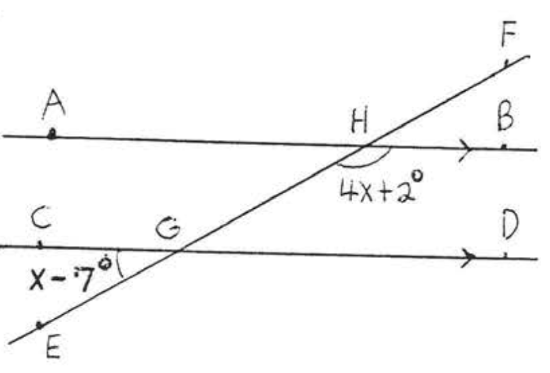

17.  18.

18.

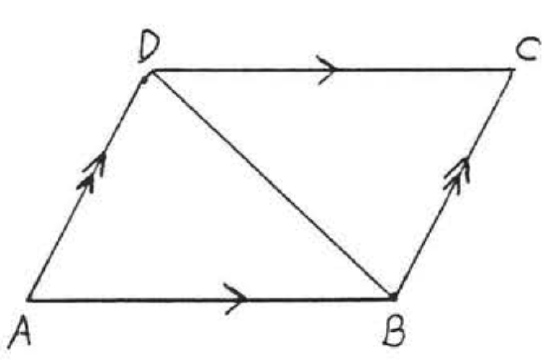

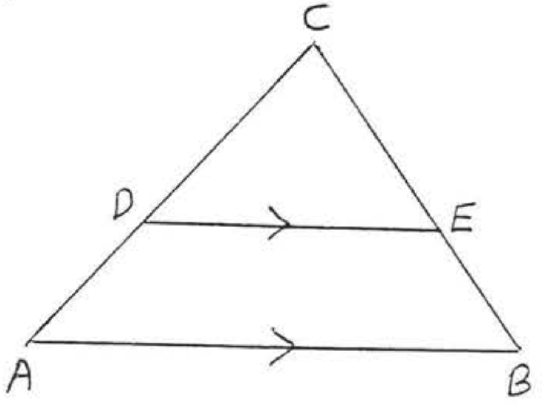

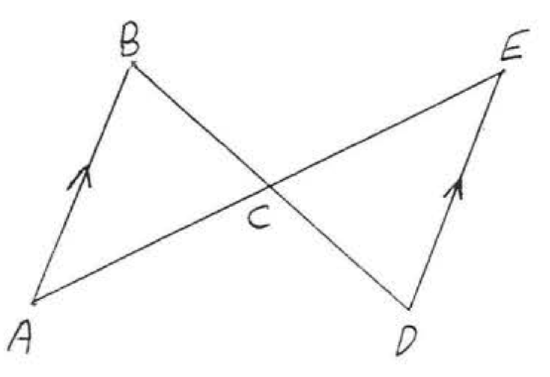

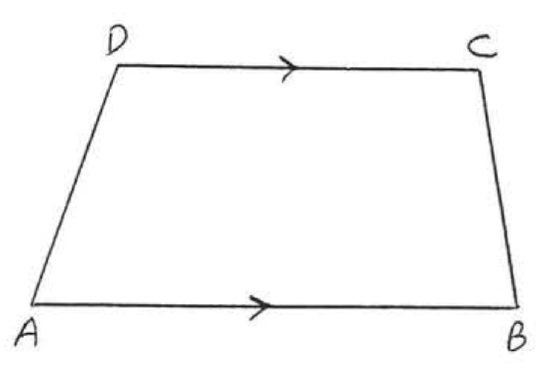

19 - 26. For each of the following, list all pairs of alternate interior angles and corresponding angles, If there are none, then list all pairs of interior angles on the same side of the transversal. Indicate the parallel lines which form each pair of angles.

19.  20.

20.

21.  22.

22.

23.  24.

24.

25.  26.

26.

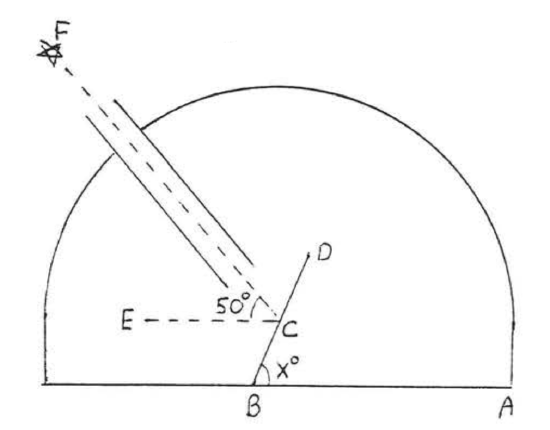

27. A telescope is pointed at a star \(50^{\circ}\) above the horizon. What angle \(x^{\circ}\) must the mirror \(BD\) make wiht the horizontal so that the star can be seen in the eyepiece \(E\)?

28. A periscope is used by sailors in a submarine to see objects on the surface of the water, If \(\angle ECF = 90^{\circ}\), what angle \(x^{\circ}\) does the mirror \(BD\) make with the horizontal?