16.4: Stereographic projection

- Page ID

- 23685

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

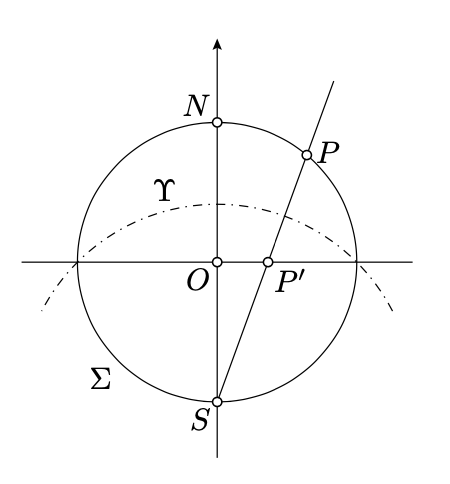

Consider the unit sphere \(\Sigma\) centered at the origin \((0,0,0)\). This sphere can be described by the equation \(x^2+y^2+z^2=1\).

Suppose that \(\Pi\) denotes the \(xy\)-plane; it is defined by the equation \(z = 0\). Clearly, \(\Pi\) runs thru the center of \(\Sigma\).

Let \(N = (0, 0, 1)\) and \(S=(0, 0, -1)\) denote the "north" and "south" poles of \(\Sigma\); these are the points on the sphere that have extremal distances to \(\Pi\). Suppose that \(\Omega\) denotes the “equator” of \(\Sigma\); it is the intersection \(\Sigma \cap \Pi\).

For any point \(P\ne S\) on \(\Sigma\), consider the line \((SP)\) in the space. This line intersects \(\Pi\) in exactly one point, denoted by \(P'\). Set \(S'=\infty\).

The map \(\xi_s\: P\mapsto P'\) is called the stereographic projection from \(\Sigma\) to \(\Pi\) with respect to the south pole. The inverse of this map \(\xi^{-1}_s\: P' \mapsto P\) is called the stereographic projection from \(\Pi\) to \(\Sigma\) with respect to the south pole.

The same way, one can define the stereographic projections \(\xi_n\) and \(\xi^{-1}_n\) with respect to the north pole \(N\).

Note that \(P=P'\) if and only if \(P\in\Omega\).

Note that if \(\Sigma\) and \(\Pi\) are as above, then the composition of the stereographic projections \(\xi_s: \Sigma\to\Pi\) and \(\xi^{-1}_s: \Pi\to\Sigma\) are the restrictions to \(\Sigma\) and \(\Pi\) respectively of the inversion in the sphere \(\Upsilon\) with the center \(S\) and radius \(\sqrt{2}\).

From above and Theorem 16.3.1, it follows that the stereographic projection preserves the angles between arcs; more precisely the absolute value of the angle measure between arcs on the sphere.

This makes it particularly useful in cartography. A map of a big region of earth cannot be done on a constant scale, but using a stereographic projection, one can keep the angles between roads the same as on earth.

In the following exercises, we assume that \(\Sigma\), \(\Pi\), \(\Upsilon\), \(\Omega\), \(O\), \(S\), and \(N\) are as above.

Show that \(\xi_n \circ \xi^{-1}_s\), the composition of stereographic projections from \(\Pi\) to \(\Sigma\) from \(S\), and from \(\Sigma\) to \(\Pi\) from \(N\) is the inverse of the plane \(\Pi\) in \(\Omega\).

- Hint

-

Note that points on \(\Omega\) do not move. Moreover, the points inside \(\Omega\) are mapped outside of \(\Omega\) and the other way around.

Further, note that this map sends circles to circles; moreover, the perpendicular circles are mapped to perpendicular circles. In particular, the circles perpendicular to \(\Omega\) are mapped to themselves.

Consider arbitrary point \(P \not\in \Omega\). Suppose that \(P'\) denotes the inverse of \(P\) in \(\Omega\). Choose two distinct circles that pass thru \(P\) and \(P'\). According to Corollary 10.5.2, \(\Gamma_1 \perp \Omega\) and \(\Gamma_2 \perp \Omega\).

Therefore, the inverse in \(\Omega\) sends \(\Gamma_1\) to itself and the same holds for \(\Gamma_2\).

The image of \(P\) has to lie on \(\Gamma_1\) and \(\Gamma_2\). Since the image of \(P\) is distinct from \(P\), we get that it has to be \(P'\).

Show that a stereographic projection \(\Sigma\to\Pi\) sends the great circles to plane circlines that intersect \(\Omega\) at opposite points.

- Hint

-

Apply Theorem 16.3.1(b).

The following exercise is analogous to Lemma 13.5.1.

Fix a point \(P\in \Pi\) and let \(Q\) be another point in \(\Pi\). Let \(P'\) and \(Q'\) denote their stereographic projections to \(\Sigma\). Set \(x=PQ\) and \(y=P'Q'_s\). Show that

\(\lim_{x\to 0} \dfrac{y}{x}=\dfrac{2}{1+OP^2}.\)

- Hint

-

Set \(z = P'Q'\). Note that \(\dfrac{y}{x} \to 1\) as \(x \to 0\).

It remains to shwo that

\(\lim_{x \to 0} \dfrac{z}{x} = \dfrac{2}{OP^2}\)

Recall that the stereographic projection is the inversion in the sphere \(Upsilon\) with the center at the south pole \(S\) restricted to the plane \(\Pi\). Show that there is a plane \(\Lambda\) passing thru \(S, P, Q, P'\), and \(Q'\). In the plane \(\Lambda\), the map \(Q \mapsto Q'\) is an inversion in the circle \(\Upsilon \cap \Lambda\).

This reduces the problem to Euclidean plane geometry. The remaining calculations in \(\Lambda\) are similar to those in the proof of Lemma 13.5.1.