7.7: LU Redux

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Certain matrices are easier to work with than others. In this section, we will see how to write any square matrix M as the product of two simpler matrices. We will write M=LU, where:

1. L is lower triangular. This means that all entries above the main diagonal are zero. In notation, L=(lij) with lij=0 for all j>i.

L=(l1100⋯l21l220⋯l31l32l33⋯⋮⋮⋮⋱)

2. U is upper triangular. This means that all entries below the main diagonal are zero. In notation, U=(uij) with uij=0 for all j<i.

U=(u11u12u13⋯0u22u23⋯00u33⋯⋮⋮⋮⋱)

M=LU is called an LU decomposition of M.

This is a useful trick for computational reasons; it is much easier to compute the inverse of an upper or lower triangular matrix than general matrices. Since inverses are useful for solving linear systems, this makes solving any linear system associated to the matrix much faster as well. The determinant---a very important quantity associated with any square matrix---is very easy to compute for triangular matrices.

Example 7.7.1:

Linear systems associated to upper triangular matrices are very easy to solve by back substitution.

$$\left(ab10ce\right) \Rightarrow \ y=\frac{e}{c}\, , \quad x=\frac{1}{a}\left(1-\frac{be}{c}\right)\]

(100da10ebc1f)⇒x=d,y=e−ad,z=f−bd−c(e−ad)

For lower triangular matrices, back substitution gives a quick solution; for upper triangular matrices, forward substitution gives the solution.

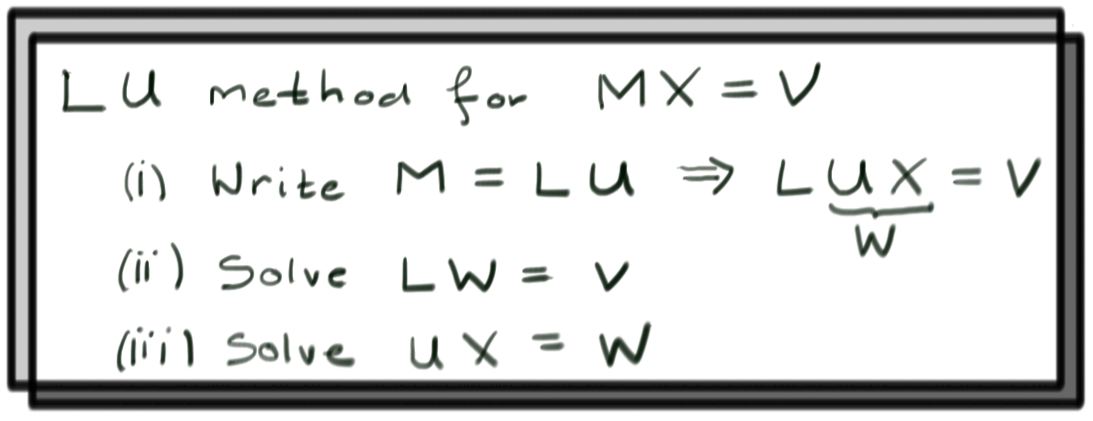

Using LU Decomposition to Solve Linear Systems

Suppose we have M=LU and want to solve the system

MX=LUX=V.

- Step 1: Set W=(uvw)=UX.

- Step 2: Solve the system LW=V. This should be simple by forward substitution since L is lower triangular. Suppose the solution to LW=V is W0.

- Step 3: Now solve the system UX=W0. This should be easy by backward substitution, since U is upper triangular. The solution to this system is the solution to the original system.

We can think of this as using the matrix L to perform row operations on the matrix U in order to solve the system; this idea also appears in the study of determinants.

Example 7.7.2:

Consider the linear system:

6x+18y+3z=32x+12y+z=194x+15y+3z=0

An LU decomposition for the associated matrix M is:

(618321214153)=(300160231)(261010001).

Step 1: Set W=(uvw)=UX.

Step 2: Solve the system LW=V:

(300160231)(uvw)=(3190)

By substitution, we get u=1, v=3, and w=−11. Then W0=(13−11)

Step 3: Solve the system UX=W0.

(261010001)(xyz)=(13−11)

Back substitution gives z=−11,y=3, and x=−3.

Then X=(−33−11), and we're done.

Finding an LU Decomposition.

In Section 2.3, Gaussian elimination was used to find LU matrix decompositions. These ideas are presented here again as review. For any given matrix, there are actually many different LU decompositions. However, there is a unique LU decomposition in which the L matrix has ones on the diagonal. In that case L is called a lower unit triangular matrix.

To find the LU decomposition, we'll create two sequences of matrices L1,L2,… and U1,U2,… such that at each step, LiUi=M. Each of the Li will be lower triangular, but only the last Ui will be upper triangular. The main trick for this calculation is captured by the following example:

Example 7.7.3: An Elementary Matrix

Consider E=(10λ1),M=(abc⋯def⋯).

Lets compute EM

EM=(abc⋯d+λae+λbf+λc⋯).

Something neat happened here: multiplying M by E performed the row operation R2→R2+λR1 on M.

Another interesting fact:

\[E^{-1}:=(10−λ1)$$

obeys (check this yourself...)

E−1E=1.$$Hence\(M=E−1EM\)or,writingthisout$$(abc⋯def⋯)=(10−λ1)(abc⋯d+λae+λbf+λc⋯).

Here the matrix on the left is lower triangular, while the matrix on the right has had a row operation performed on it.

We would like to use the first row of M to zero out the first entry of every row below it. For our running example, M=(618321214153), so we would like to perform the row operations $$R_{2}\to R_{2} -\frac{1}{3}R_{1} \mbox{ and } R_{3}\to R_{3}-\frac{2}{3}R_{1}\, .\]

If we perform these row operations on M to produce

$$U_1=(6183060031)\, ,\]

we need to multiply this on the left by a lower triangular matrix L1 so that the product L1U1=M still.

The above example shows how to do this: Set L1 to be the lower triangular matrix whose first column is filled with minus the constants used to zero out the first column of M. Then $$L_{1} = (10013102301)\, .\]

By construction L1U1=M, but you should compute this yourself as a double check.

Now repeat the process by zeroing the second column of U1 below the diagonal using the second row of U1 using the row operation R3→R3−12R2 to produce

U2=(6183060001).

The matrix that undoes this row operation is obtained in the same way we found L1 above and is:

\[

(1000100120)\, .

Thusouranswerfor\(L2\)istheproductofthismatrixwith\(L1\),namely

L_{2}=

(10013102301)(1000100120)

=(100131023121)\, .

$$

Notice that it is lower triangular because

The product of lower triangular matrices is always lower triangular!

Moreover it is obtained by recording minus the constants used for all our row operations in the appropriate columns (this always works this way). Moreover, U2 is upper triangular and M=L2U2, we are done! Putting this all together we have

M=(618321214153)=(100131023121)(6183060001).

If the matrix you're working with has more than three rows, just continue this process by zeroing out the next column below the diagonal, and repeat until there's nothing left to do.

The fractions in the L matrix are admittedly ugly. For two matrices LU, we can multiply one entire column of L by a constant λ and divide the corresponding row of U by the same constant without changing the product of the two matrices. Then:

For matrices that are not square, LU decomposition still makes sense. Given an m×n matrix M, for example we could write M=LU with L a square lower unit triangular matrix, and U a rectangular matrix. Then L will be an m×m matrix, and U will be an m×n matrix (of the same shape as M). From here, the process is exactly the same as for a square matrix. We create a sequence of matrices Li and Ui that is eventually the LU decomposition. Again, we start with L0=I and U0=M.

Example 7.7.4:

Let's find the LU decomposition of

M=U0=(−213−441).

Since M is a 2×3 matrix, our decomposition will consist of a 2×2 matrix and a 2×3 matrix. Then we start with L0=I2=(1001).

The next step is to zero-out the first column of M below the diagonal. There is only one row to cancel, then, and it can be removed by subtracting 2 times the first row of M to the second row of M. Then:

L1=(1021),U1=(−21302−5)

Since U1 is upper triangular, we're done. With a larger matrix, we would just continue the process.

Block LDU Decomposition

Let M be a square block matrix with square blocks X,Y,Z,W such that X−1 exists. Then M can be decomposed as a block LDU decomposition, where D is block diagonal, as follows:

M=(XYZW)

Then:

$$M=\left(I0ZX−1I\right)

\left(X00W−ZX−1Y\right)\left(IX−1Y0I\right)\, .\]

This can be checked explicitly simply by block-multiplying these three matrices.

Example 7.7.15:

For a 2×2 matrix, we can regard each entry as a 1×1 block.

(1234)=(1031)(100−2)(1201)

By multiplying the diagonal matrix by the upper triangular matrix, we get the standard LU decomposition of the matrix.