23.2: The arithmetic sequence

- Page ID

- 54477

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)We have already encountered examples of arithmetic sequences in the previous section. An arithmetic sequence is a sequence for which we add a constant number to get from one term to the next, for example:

\[8,\underset{+3}{\hookrightarrow } 11,\underset{+3}{\hookrightarrow } 14, \underset{+3}{\hookrightarrow } 17, \underset{+3}{\hookrightarrow } 20, \underset{+3}{\hookrightarrow } 23, \dots \nonumber \]

A sequence \(\{a_n\}\) is called an arithmetic sequence if any two consecutive terms have a common difference \(d\). The arithmetic sequence is determined by \(d\) and the first value \(a_1\). This can be written recursively as:

\[a_n=a_{n-1}+d \quad \quad \text{for }n\geq 2 \nonumber \]

Alternatively, we have the general formula for the \(n\)th term of the arithmetic sequence:

\[\label{EQU:arithmetic-sequence-general-term} \boxed{a_n=a_1+d\cdot (n-1)}\]

Determine if the sequence is an arithmetic sequence. If so, then find the general formula for \(a_n\) in the form of equation \(\ref{EQU:arithmetic-sequence-general-term}\).

- \(7,13, 19, 25, 31, \dots\)

- \(13, 9, 5, 1, -3, -7, \dots\)

- \(10, 13, 16, 20, 23, \dots\)

- \(a_n=8\cdot n +3\)

Solution

- Calculating the difference between two consecutive terms always gives the same answer \(13-7=6\), \(19-13=6\), \(25-19=6\), etc. Therefore the common difference \(d=6\), which shows that this is an arithmetic sequence. Furthermore, the first term is \(a_1=7\), so that the general formula for the \(n\)th term is \(a_n=7+6\cdot (n-1)\).

- One checks that the common difference is \(9-13=-4\), \(5-9=-4\), etc., so that this is an arithmetic sequence with \(d=-4\). Since \(a_1=13\), the general term is \(a_n=13-4\cdot(n-1)\).

- We have \(13-10=3\), but \(20-16=4\), so that this is not an arithmetic sequence.

- If we write out the first couple of terms of \(a_n=8n+3\), we get the sequence:

\[11, 19, 27, 35, 43, 51, \dots \nonumber \]

From this it seems reasonable to suspect that this is an arithmetic sequence with common difference \(d=8\) and first term \(a_1=11\). The general term of such an arithmetic sequence is

\[a_1+d(n-1)=11+8(n-1)=11+8n-8=8n+3=a_n \nonumber \]

This shows that \(a_n=8n+3=11+8(n-1)\) is an arithmetic sequence.

Find the general formula of an arithmetic sequence with the given property.

- \(d=12\), and \(a_6=68\)

- \(a_1=-5\), and \(a_{9}=27\)

- \(a_{5}=38\), and \(a_{16}=115\)

Solution

- According to equation \(\ref{EQU:arithmetic-sequence-general-term}\) the general term is \(a_n=a_1+d(n-1)\). We know that \(d=12\), so that we only need to find \(a_1\). Plugging \(a_6=68\) into \(a_n=a_1+d(n-1)\), we may solve for \(a_1\):

\[68=a_6=a_1+12\cdot (6-1)=a_1+12\cdot 5=a_1+60 \,\, \stackrel{(-60)}{\implies} \,\, a_1=68-60=8 \nonumber \]

The \(n\)th term is therefore, \(a_n=8+12\cdot (n-1)\).

- In this case, we are given \(a_1=-5\), but we still need to find the common difference \(d\). Plugging \(a_9=27\) into \(a_n=a_1+d(n-1)\), we obtain

\[\begin{aligned} 27=a_9&=-5+d\cdot(9-1)\\&= -5+8d \\ \stackrel{(+5)}{\implies} 32&=8d \\ \stackrel{(\div 8)}{\implies} 4&=d \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

The \(n\)th term is therefore, \(a_n=-5+4\cdot (n-1)\).

- In this case we neither have \(a_1\) nor \(d\). However, the two conditions \(a_{5}=38\) and \(a_{16}=115\) give two equations in the two unknowns \(a_1\) and \(d\).

\[\left\{\begin{array} { c }

{ 3 8 = a _ { 5 } = a _ { 1 } + d ( 5 - 1 ) } \\

{ 1 1 5 = a _ { 1 6 } = a _ { 1 } + d ( 1 6 - 1 ) }

\end{array} \quad \Longrightarrow \left\{\begin{array}{c}

38=a_{1}+4 \cdot d \\

115=a_{1}+15 \cdot d

\end{array}\right.\right. \nonumber \]

To solve this system of equations, we need to recall the methods for doing so. One convenient method is the addition/subtraction method. For this, we subtract the top from the bottom equation:

\[\begin{matrix} & 115 & = & a_1 & +15\cdot d & \\ - (& 38 & = & a_1& +4\cdot d & ) \\ \hline & 77 & = & & +11\cdot d & \\ \end{matrix} \begin{matrix} \, \\ \, \\ \quad\quad \stackrel{(\div 11)}{\implies} \quad\quad 7=d \end{matrix} \nonumber \]

Plugging \(d=7\) into either of the two equations gives \(a_1\). We plug it into the first equation \(38=a_1+4d\):

\[38=a_1+4\cdot 7 \quad\implies \quad 38=a_1+28 \quad \stackrel{(-28)}{\implies} \quad 10=a_1 \nonumber \]

Therefore, the \(n\)th term is given by \(a_n=10+7\cdot (n-1)\).

We can sum the first \(k\) terms of an arithmetic sequence using a trick, which, according to lore, was found by the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss when he was a child at school.

Find the sum of the first \(100\) integers, starting from \(1\).

Solution

In other words, we want to find the sum of \(1+2+3+\dots + 99+100\). First, note that he sequence \(1, 2, 3, \dots\) is an arithmetic sequence. The main idea for solving this problem is a trick, which will indeed work for any arithmetic sequence:

Let \(S=1+2+3+\cdots+98+99+100\) be what we want to find. Note that

\[2S=\begin{array}{ccccccccccccc}&1&+&2&+&3&\cdots&+&98&+&99&+&100\\ +&100&+&99&+&98&\cdots&+&3&+&2&+&1 \end{array} \nonumber \]

Note that the second line is also \(S\) but is added in the reverse order. Adding vertically we see then that

\[2S=101+101+101+\cdots+101+101+101, \nonumber \]

where there are \(100\) terms on the right hand side. So

\[2S=100\cdot101{\text{ and therefore }}S=\frac{100\cdot101}{2}=5050 \nonumber \]

The previous example generalizes to the more general setting starting with an arbitrary arithmetic sequence.

Let \(\{a_n\}\) be an arithmetic sequence, whose \(n\)th term is given by the formula \(a_n=a_1+d(n-1)\). Then, the sum \(a_1+a_2+\dots+a_{k-1}+a_k\) is given by adding \((a_1+a_k)\) precisely \(\dfrac k 2\) times:

\[\label{EQU:arithmetic-series} \boxed{\sum_{i=1}^k a_i =\dfrac{k}{2}\cdot (a_1+a_k)}\]

In order to remember the formula above, it may be convenient to think of the right hand side as \(k\cdot\dfrac{a_1+a_k}{2}\) (this is, \(k\) times the average of the first and the last term).

- Proof

-

For the proof of equation \(\ref{EQU:arithmetic-series}\), we write \(S= a_1+a_2+\dots +a_{k-1}+a_{k}\). We then add it to itself but in reverse order:

\[2S=\begin{array}{ccccccccccccc}&a_1&+&a_2&+&a_3&\cdots&+&a_{k-2}&+&a_{k-1}&+&a_k\\ +&a_{k}&+&a_{k-1}&+&a_{k-2}&\cdots&+&a_3&+&a_2&+&a_1 \end{array} \nonumber \]

Now note that in general \(a_l+a_m=2a_1+d(l+m-2)\). We see that adding vertically gives

\[2S=k(2a_1+d(k-1))=k(a_1+(a_1+d(k-1))=k(a_1+a_k) \nonumber \]

Dividing by \(2\) gives the desired result.

Find the value of the arithmetic series.

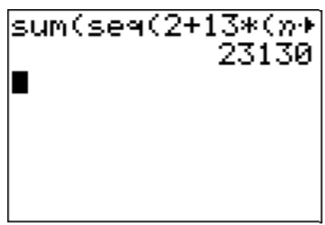

- Find the sum \(a_1+\dots +a_{60}\) for the arithmetic sequence \(a_n=2+13(n-1)\).

- Determine the value of the sum: \(\sum\limits_{j=1}^{1001} (5-6j)\)

- Find the sum of the first \(35\) terms of the sequence \[4, 3.5, 3, 2.5, 2, 1.5, \dots \nonumber \]

Solution

- The sum is given by the formula \(\ref{EQU:arithmetic-series}\): \(\sum_{i=1}^k a_i=\dfrac k 2 \cdot (a_1+a_k)\). Here, \(k=60\), and \(a_1=2\) and \(a_{60}=2+13\cdot(60-1)=2+13\cdot 59=2+767=769\). We obtain a sum of

\[a_1+\dots +a_{60}=\sum_{i=1}^{60} a_i=\dfrac{60}{2}\cdot (2+769)=30\cdot 771=23130 \nonumber \]

We may confirm this with the calculator as described in example 23.1.5 in the previous section.

\[\text{Enter: } \operatorname{sum}(\operatorname{seq}((2+13 \cdot(n-1), n, 1,60)) \nonumber \]

- Again, we use the above formula \(\sum_{j=1}^k a_j=\dfrac k 2 \cdot (a_1+a_k)\), where the arithmetic sequence is given by \(a_j=5-6j\) and \(k=1001\). Using the values \(a_1=5-6\cdot 1=5-6=-1\) and \(a_{1001}=5-6\cdot 1001=5-6006=-6001\), we obtain:

\[\begin{aligned} \sum_{j=1}^{1001} (5-6j)& = \dfrac{1001}{2}(a_1+a_{1001})\\&=\dfrac{1001}{2}((-1)+(-6001))\\ &= \dfrac{1001}{2}\cdot (-6002)\\& = 1001\cdot (-3001)\\& =-3004001\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

- First note that the given sequence \(4, 3.5, 3, 2.5, 2, 1.5, \dots\) is an arithmetic sequence. It is determined by the first term \(a_1=4\) and common difference \(d=-0.5\). The \(n\)th term is given by \(a_n=4-0.5\cdot (n-1)\), and summing the first \(k=35\) terms gives:

\[\sum_{i=1}^{35} a_i=\dfrac{35}{2}\cdot (a_1+a_{35}) \nonumber \]

We see that we need to find \(a_{35}\) in the above formula:

\[a_{35}=4-0.5\cdot (35-1)=4-0.5\cdot 34=4-17=-13 \nonumber \]

This gives a total sum of

\[\sum_{i=1}^{35} a_i=\dfrac{35}{2}\cdot (4+(-13))=\dfrac{35}{2}\cdot (-9)=\dfrac{-315}{2} \nonumber \]

The answer may be written as a fraction or also as a decimal, that is: \(\sum_{i=1}^{35}a_i=\dfrac{-315}2=-157.5\).