1.2: Determining Volumes by Slicing

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Volume and the Slicing Method

Let’s motivate a new theorem (the basis for all future theorems on volumes).

The volume of a solid isV=limn→∞n∑i=1A(λ∗i)Δλ=∫baA(λ)dλ,where A(λ∗i) is the cross-sectional area at the ith slice and Δλ is the "thickness" of the slice.

Non-Rotational Volumes

Common Volumes

Find the volume of a pyramid with height h and rectangular base with dimensions b and 2b.

Uncommon Volumes

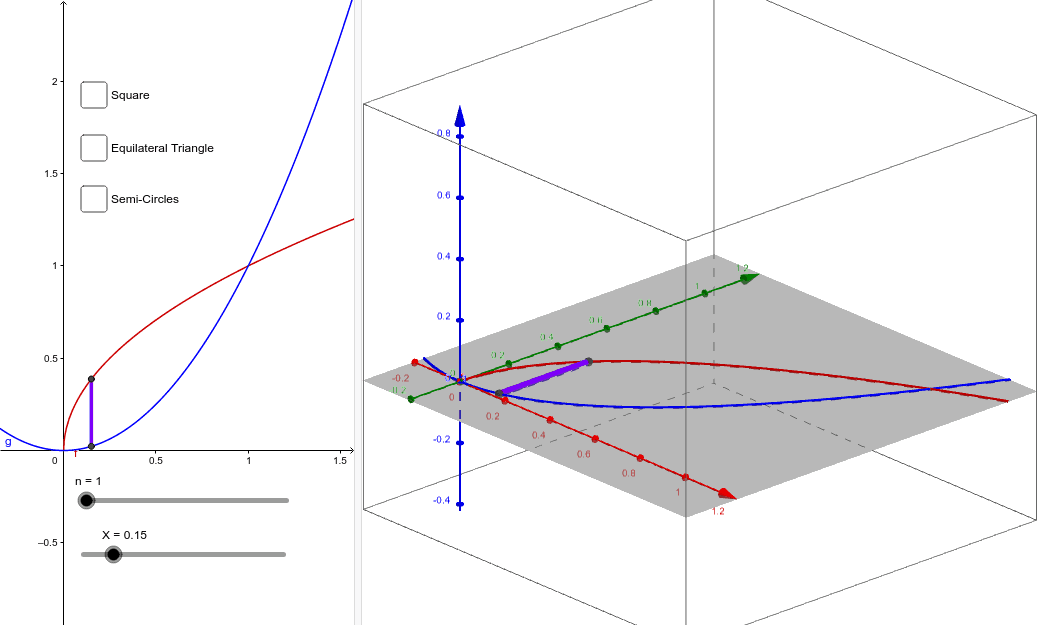

Description: This Geogebra applet allows you to visualize how a solid of known cross-sections is generated by placing cross-sectional slices perpendicular to the x-axis on a base defined by the boundary between two function (red and blue) from x=0 to X, where you can adjust X using the bottom slider.

Interact: Adjust the rightmost boundary, X, of the region to whatever value you want, select a single cross-sectional shape (square, equilateral triangle, or semi-circle), increase n to a decent number of slices to help you visualize what is going on, and (finally) use your mouse to adjust the graph of the right side of the applet to see the resulting solid.

Find the volume of the solid with the base being the elliptical region 9x2+4y2=36, where cross-sections perpendicular to the x-axis are isosceles right triangles with hypotenuse in the base.

Rotational Volumes

The Disk Method

Let f(λ) be continuous on an interval λ=a to λ=b. The volume obtained by rotating this function about the λ-axis isV=∫λ=bλ=aA(λ)dλ,where A(λ)=πr(λ)2 is the cross-sectional area at λ. Hence,V=∫λ=bλ=aπr(λ)2dλ.

Find the volume of the solid obtained by rotating the region bounded byy=ex,y=0,x=−1,x=1about the x-axis.

The Washer Method

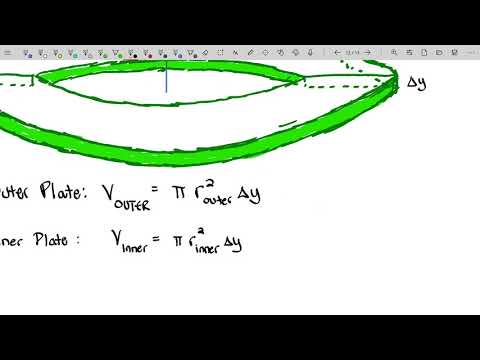

What if someone wanted to drill a hole in our rotational solid?

If the region to be rotated is bounded by the functions f(λ) and g(λ), thenA(λ)=π[(outer radius)2−(inner radius)2].

A very common mistake is to think that the volume in the previous theorem is∫baπ[f(x)−g(x)]2dx(if rotating about the x-axis). This is why I strongly encourage not to memorize that formula, but instead to derive it until it makes sense. I will demonstrate this process with each remaining problem.

Find the volume of the solid obtained by rotating the region bounded byy2=x,x=2yabout the y-axis.

Vote for One of the Following!

Find the volume of the solid obtained by rotating the region bounded byy=1+sec(x),y=3about y=1.

- OR -

Determine the volume of the solid obtained by rotating the region bounded by y=cos(x),y=sin(x)about y=−1 on the interval [0,π4].

Synthesis Questions

Set up an integral for the volume of a solid torus with radii r and R. By interpreting the integral as an area, find the volume of the torus.