Arc Length

In previous sections we have used integration to answer the following questions:

- Given a region, what is its area?

- Given a solid, what is its volume?

In this section, we address a related question: Given a curve, what is its length? This is often referred to as arc length.

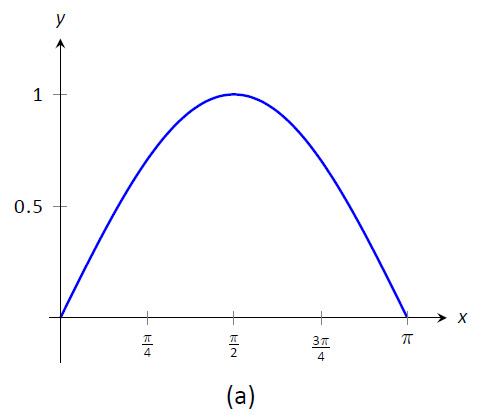

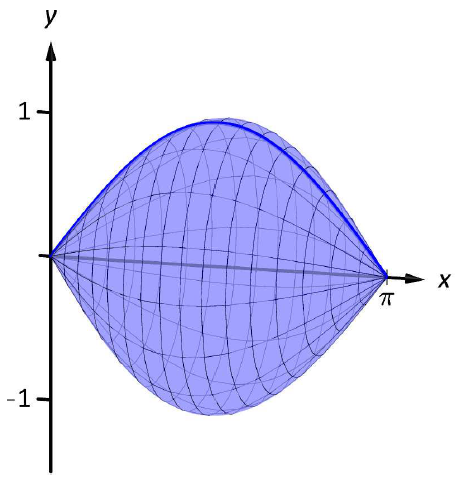

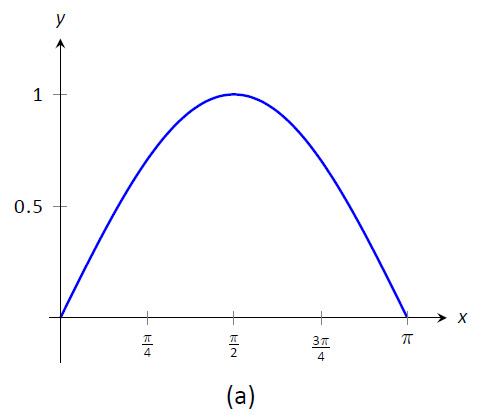

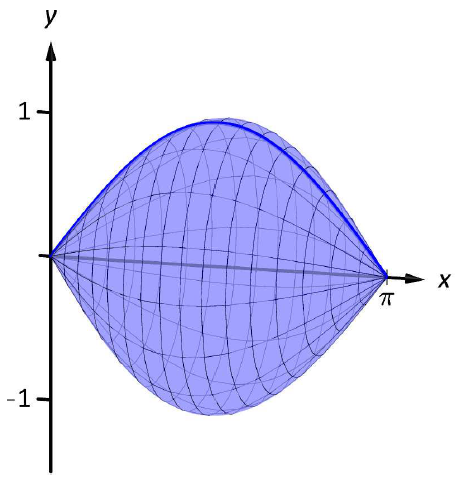

Consider the graph of \(y=\sin x\) on \([0,\pi]\) given in Figure \(\PageIndex{1a}\). How long is this curve? That is, if we were to use a piece of string to exactly match the shape of this curve, how long would the string be?

As we have done in the past, we start by approximating; later, we will refine our answer using limits to get an exact solution.

The length of straight--line segments is easy to compute using the Distance Formula. We can approximate the length of the given curve by approximating the curve with straight lines and measuring their lengths.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Graphing \(y=\sin x\) on \([0,\pi]\) and approximating the curve with line segments.

In Figure \(\PageIndex{1b}\), the curve \(y=\sin x\) has been approximated with 4 line segments (the interval \([0,\pi]\) has been divided into 4 equally--lengthed subintervals). It is clear that these four line segments approximate \(y=\sin x\) very well on the first and last subinterval, though not so well in the middle. Regardless, the sum of the lengths of the line segments is \(3.79\), so we approximate the arc length of \(y=\sin x\) on \([0,\pi]\) to be \(3.79\).

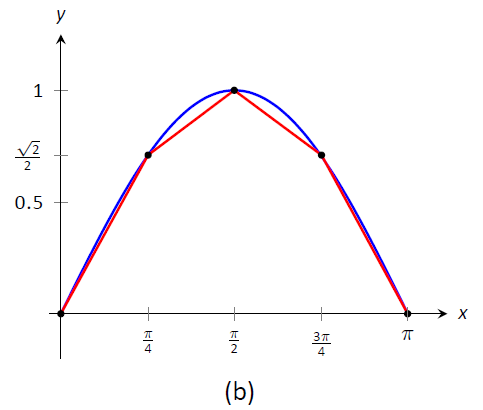

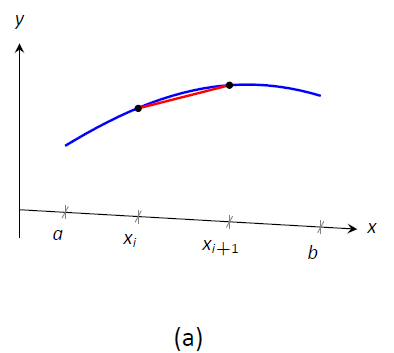

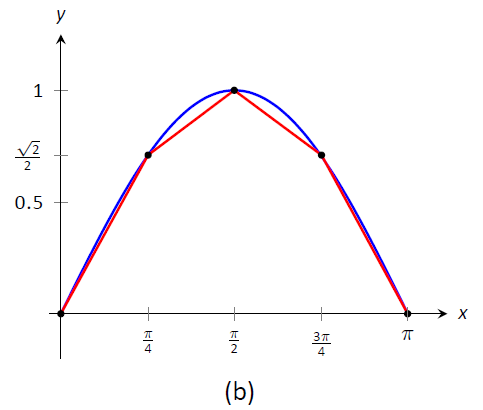

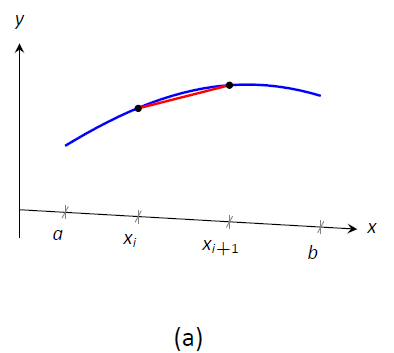

In general, we can approximate the arc length of \(y=f(x)\) on \([a,b]\) in the following manner. Let \(a=x_1 < x_2 < \ldots < x_n< x_{n+1}=b\) be a partition of \([a,b]\) into \(n\) subintervals. Let \(dx_i\) represent the length of the \(i\,^\text{th}\) subinterval \([x_i,x_{i+1}]\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Zooming in on the \(i\,^\text{th}\) subinterval \([x_i,x_{i+1}\)] of a partition of \([a,b]\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) zooms in on the \(i\,^\text{th}\) subinterval where \(y=f(x)\) is approximated by a straight line segment. The dashed lines show that we can view this line segment as they hypotenuse of a right triangle whose sides have length \(dx_i\) and \(dy_i\). Using the Pythagorean Theorem, the length of this line segment is \(\sqrt{dx_i^2 + \Delta y_i^2}.\) Summing over all subintervals gives an arc length approximation

\[L \approx \sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{dx_i^2 + \Delta y_i^2}.\]

As shown here, this is not a Riemann Sum. While we could conclude that taking a limit as the subinterval length goes to zero gives the exact arc length, we would not be able to compute the answer with a definite integral. We need first to do a little algebra.

In the above expression factor out a \(dx_i^2\) term:

\[ \sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{dx_i^2 + \Delta y_i^2} = \sum_{i=1}^n \sqrt{dx_i^2\left(1 + \frac{\Delta y_i^2}{dx_i^2}\right)}.\]

Now pull the \(dx_i^2\) term out of the square root:

\[= \sum_{i=1}^n\sqrt{1 + \frac{\Delta y_i^2}{dx_i^2}}\ dx_i.\]

This is nearly a Riemann Sum. Consider the \(\Delta y_i^2/dx_i^2\) term. The expression \(\Delta y_i/dx_i\) measures the "change in \(y\)/change in \(x\)," that is, the "rise over run" of \(f\) on the \(i\,^\text{th}\) subinterval. The Mean Value Theorem of Differentiation (Theorem 3.2.1) states that there is a \(c_i\) in the \(i\,^\text{th}\) subinterval where \(f'(c_i) = \Delta y_i/dx_i\). Thus we can rewrite our above expression as:

\[= \sum_{i=1}^n\sqrt{1+f'(c_i)^2}\ dx_i.\]

This is a Riemann Sum. As long as \(f'\) is continuous, we can invoke Theorem 5.3.2 and conclude

\[= \int_a^b\sqrt{1+f'(x)^2}\ dx.\]

Key Idea 27: Arc Length

Let \(f\) be differentiable on an open interval containing \([a,b]\), where \(f'\) is also continuous on \([a,b]\). Then the arc length of \(f\) from \(x=a\) to \(x=b\) is

\[L = \int_a^b \sqrt{1+f'(x)^2}\ dx.\]

As the integrand contains a square root, it is often difficult to use the formula in Key Idea 27 to find the length exactly. When exact answers are difficult to come by, we resort to using numerical methods of approximating definite integrals. The following examples will demonstrate this.

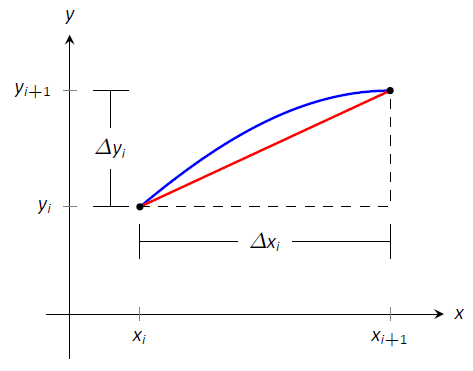

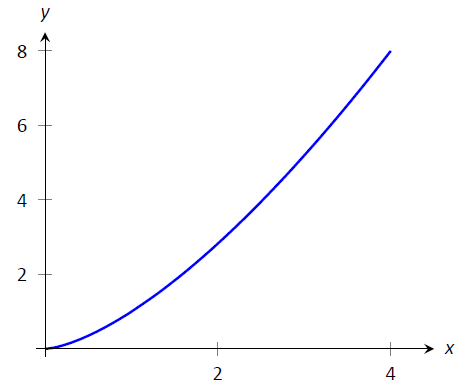

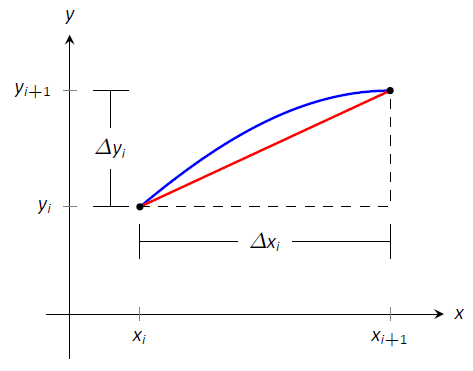

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Finding arc length

Find the arc length of \(f(x) = x^{3/2}\) from \(x=0\) to \(x=4\).

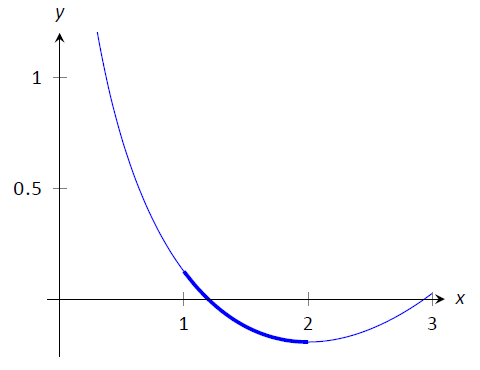

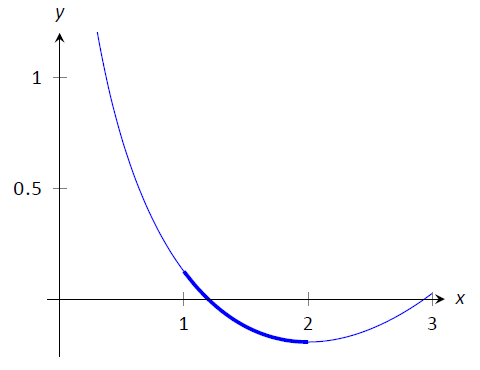

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): A graph of \(f(x) = x^{3/2}\) from Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Solution

We begin by finding \(f'(x)= \frac32x^{1/2}\). Using the formula, we find the arc length \(L\) as

\[\begin{align} L &= \int_0^4 \sqrt{1+\left(\frac32x^{1/2}\right)^2}\ dx \\ &= \int_0^4 \sqrt{1+\frac94x} \ dx \\ &= \int_0^4 \left(1+\frac94x\right)^{1/2}\ dx \\ &= \frac23\frac49\left(1+\frac94x\right)^{3/2}\Big|_0^4 \\ &=\frac{8}{27}\left(10^{3/2}-1\right) \approx 9.07 \text{units}.\end{align}\]

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Finding arc length

Find the arc length of \(f(x) =\frac18x^2-\ln x\) from \(x=1\) to \(x=2\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): A graph of \(f(x) =\frac18x^2-\ln x\) from Example \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Solution

This function was chosen specifically because the resulting integral can be evaluated exactly. We begin by finding \(f'(x) = x/4-1/x\). The arc length is

\[\begin{align} L&= \int_1^2 \sqrt{1+ \left(\frac x4-\frac1x\right)^2}\ dx \\ &= \int_1^2 \sqrt{1 + \frac{x^2}{16} -\frac12 + \frac1{x^2} } \ dx \\ &= \int_1^2 \sqrt{\frac{x^2}{16} +\frac12 + \frac1{x^2} } \ dx \\ &= \int_1^2 \sqrt{ \left(\frac x4 + \frac1x\right)^2}\ dx &= \int_1^2 \left(\frac x4 + \frac1x\right) \ dx \\ &= \left(\frac{x^2}8 + \ln x\right)\Bigg|_1^2\\ &= \frac38+\ln 2 \approx 1.07 \ \text{units}.\end{align}\]

A graph of \(f\) is given in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\); the portion of the curve measured in this problem is in bold.

The previous examples found the arc length exactly through careful choice of the functions. In general, exact answers are much more difficult to come by and numerical approximations are necessary.

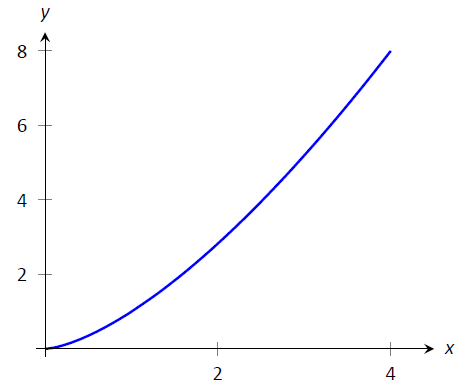

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Approximating arc length numerically

Find the length of the sine curve from \(x=0\) to \(x=\pi\).

Solution

This is somewhat of a mathematical curiosity; in Example 5.4.3 we found the area under one "hump" of the sine curve is 2 square units; now we are measuring its arc length.

The setup is straightforward: \(f(x) = \sin x\) and \(f'(x) = \cos x\). Thus

\[L = \int_0^\pi \sqrt{1+\cos^2x}\ dx.\]

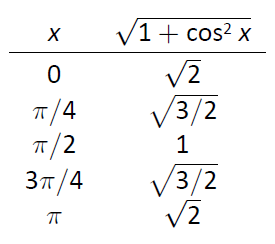

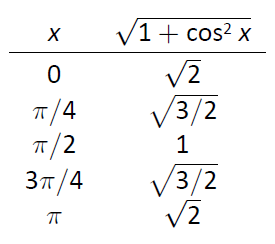

This integral cannot be evaluated in terms of elementary functions so we will approximate it with Simpson's Method with \(n=4\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): A table of values of \(y=\sqrt{1+\cos^2x}\) to evaluate a definite integral in Example \(\PageIndex{3}\).

\[\begin{array}{cc}x & \sqrt{1+\cos^2x} \\ \hline 0 & \sqrt{2}\\ \pi/4 & \sqrt{3/2} \\ \pi/2 & 1 \\ 3 \pi/4 & \sqrt{3/2} \\ \pi & \sqrt{2} \\\end{array}\]

Figure \ref{fig:arc3} gives \(\sqrt{1+\cos^2x}\) evaluated at 5 evenly spaced points in \([0,\pi]\). Simpson's Rule then states that

\[\begin{align} \int_0^\pi \sqrt{1+\cos^2x}\ dx &\approx \frac{\pi-0}{4\cdot 3}\left(\sqrt{2}+4\sqrt{3/2}+2(1)+4\sqrt{3/2}+\sqrt{2}\right) \\ &=3.82918.\end{align}\]

Using a computer with \(n=100\) the approximation is \(L\approx 3.8202\); our approximation with \(n=4\) is quite good.

Surface Area of Solids of Revolution

We have already seen how a curve \(y=f(x)\) on \([a,b]\) can be revolved around an axis to form a solid. Instead of computing its volume, we now consider its surface area.

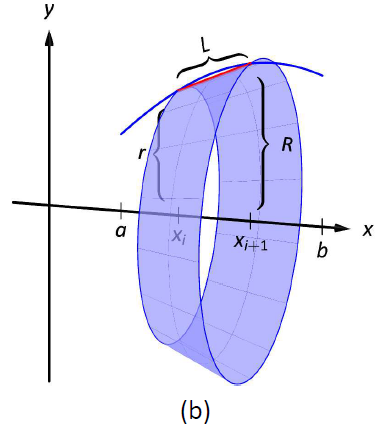

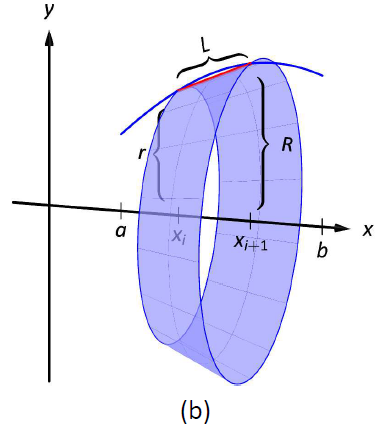

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Establishing the formula for surface area.

We begin as we have in the previous sections: we partition the interval \([a,b]\) with \(n\) subintervals, where the \(i\,^{\text{th}}\) subinterval is \([x_i,x_{i+1}]\). On each subinterval, we can approximate the curve \(y=f(x)\) with a straight line that connects \(f(x_i)\) and \(f(x_{i+1})\) as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5a}\). Revolving this line segment about the \(x\)-axis creates part of a cone (called a frustum of a cone) as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5b}\). The surface area of a frustum of a cone is

\[2\pi\cdot\text{ length }\cdot\text{average of the two radii \(R\) and \(r\)}.\]

The length is given by \(L\); we use the material just covered by arc length to state that

\[L\approx \sqrt{1+f'(c_i)}dx_i\]

for some \(c_i\) in the \(i\,^\text{th}\) subinterval. The radii are just the function evaluated at the endpoints of the interval. That is,

\[R = f(x_{i+1})\quad \text{and}\quad r = f(x_i).\]

Thus the surface area of this sample frustum of the cone is approximately

\[2\pi\frac{f(x_i)+f(x_{i+1})}2\sqrt{1+f'(c_i)^2}dx_i.\]

Since \(f\) is a continuous function, the Intermediate Value Theorem states there is some \(d_i\) in \([x_i,x_{i+1}]\) such that \(f(d_i) = \frac{f(x_i)+f(x_{i+1})}2\); we can use this to rewrite the above equation as

\[2\pi f(d_i)\sqrt{1+f'(c_i)^2}dx_i.\]

Summing over all the subintervals we get the total surface area to be approximately

\[\text{Surface Area}\approx \sum_{i=1}^n 2\pi f(d_i)\sqrt{1+f'(c_i)^2}dx_i,\]

which is a Riemann Sum. Taking the limit as the subinterval lengths go to zero gives us the exact surface area, given in the following Key Idea.

Key Idea 28: Surface Area of a Solid of Revolution

Let \(f\) be differentiable on an open interval containing \([a,b]\) where \(f'\) is also continuous on \([a,b]\).

- The surface area of the solid formed by revolving the graph of \(y=f(x)\), where \(f(x)\geq0\), about the \(x\)-axis is

\[\text{Surface Area} = 2\pi\int_a^b f(x)\sqrt{1+f'(x)^2}\ dx.\]

- The surface area of the solid formed by revolving the graph of \(y=f(x)\) about the \(y\)-axis, where \(a,b\geq0\), is

\[\text{Surface Area} = 2\pi\int_a^b x\sqrt{1+f'(x)^2}\ dx.\]

When revolving \(y=f(x)\) about the \(y\)-axis, the radii of the resulting frustum are \(x_i\) and \(x_{i+1}\); their average value is simply the midpoint of the interval. In the limit, this midpoint is just \(x\). This gives the second part of Key Idea 28.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Finding surface area of a solid of revolution

Find the surface area of the solid formed by revolving \(y=\sin x\) on \([0,\pi]\) around the \(x\)-axis, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): Revolving \(y=\sin x\) on \([0,\pi]\) about the \(x\)-axis.

Solution

The setup is relatively straightforward. Using Key Idea \ref{idea:surface_area}, we have the surface area \(SA\) is:

\[\begin{align}SA &= 2\pi\int_0^\pi \sin x\sqrt{1+\cos^2x}\ dx \\ &= -2\pi\frac12\left.\left(\sinh^{-1}(\cos x)+\cos x\sqrt{1+\cos^2x}\right)\right|_0^\pi \\ &= 2\pi\left(\sqrt{2}+\sinh^{-1} 1\right) \\ &\approx 14.42\ \text{units}^2.\end{align}\]

The integration step above is nontrivial, utilizing an integration method called Trigonometric Substitution.

It is interesting to see that the surface area of a solid, whose shape is defined by a trigonometric function, involves both a square root and an inverse hyperbolic trigonometric function.

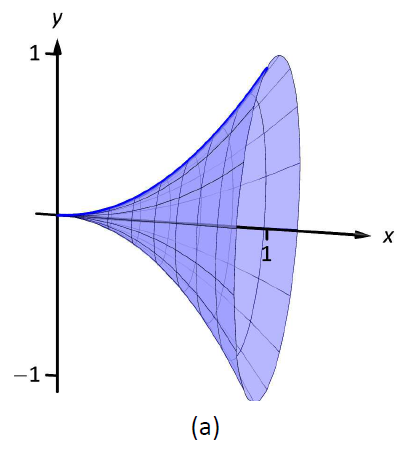

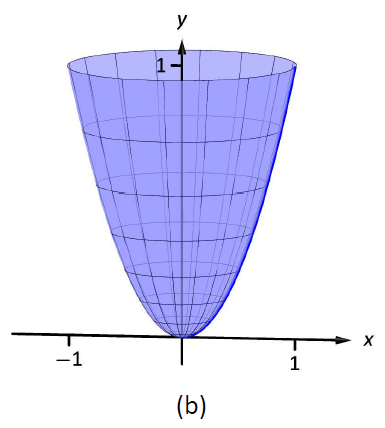

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): Finding surface area of a solid of revolution

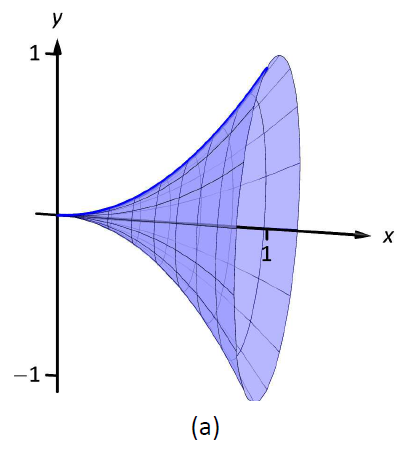

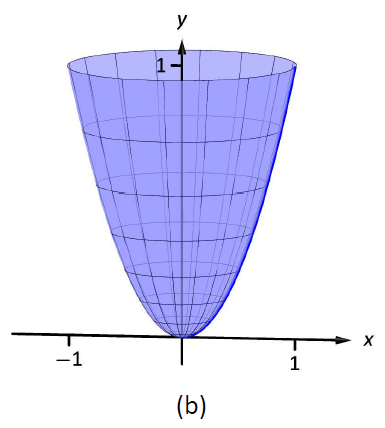

Find the surface area of the solid formed by revolving the curve \(y=x^2\) on \([0,1]\) about:

- the \(x\)-axis

- the \(y\)-axis.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): The solids used in Example \(\PageIndex{6}\).

Solution

- The integral is straightforward to setup:

\[SA = 2\pi\int_0^1 x^2\sqrt{1+(2x)^2} dx.\]

Like the integral in Example \ref{ex_sa1}, this requires Trigonometric Substitution.

\[\begin{align} &= \left.\frac{\pi}{32}\left(2(8x^3+x)\sqrt{1+4x^2}-\sinh^{-1}(2x)\right)\right|_0^1\\ &=\frac{\pi}{32}\left(18\sqrt{5}-\sinh^{-1}2\right)\\ &\approx 3.81\ \text{units}^2. \end{align}\]

The solid formed by revolving \(y=x^2\) around the \(x\)-axis is graphed in Figure \(\PageIndex{7a}\).

- Since we are revolving around the \(y\)-axis, the "radius" of the solid is not \(f(x)\) but rather \(x\). Thus the integral to compute the surface area is:

\[SA = 2\pi\int_0^1x\sqrt{1+(2x)^2} dx.\]

This integral can be solved using substitution. Set \(u=1+4x^2\); the new bounds are \(u=1\) to \(u=5\). We then have

\[\begin{align} &= \frac{\pi}{4}\int_1^5 \sqrt{u} du \\ &= \frac{\pi}{4}\frac{2}{3} u^{3/2}\big|_1^5 \\ &= \frac{\pi}{6}\left ( 5\sqrt{5}-1\right ) \\ &\approx 5.33 \text{ units}^2. \end{align}\]

The solid formed by revolving \(y=x^2\) about the \(y\)-axis is graphed in Figure \(\PageIndex{7b}\).

Our final example is a famous mathematical "paradox."

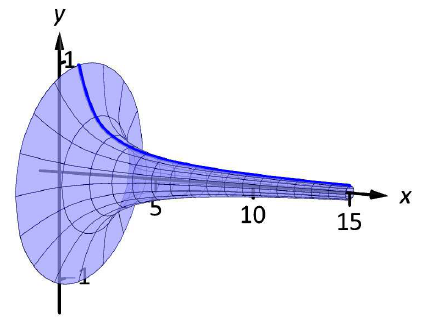

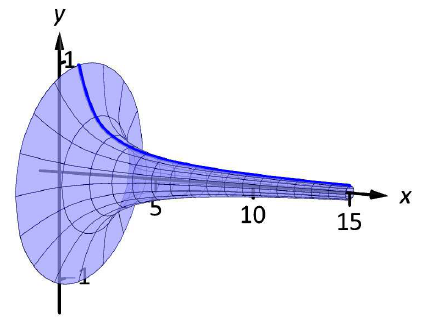

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\): The surface area and volume of Gabriel's Horn

Consider the solid formed by revolving \(y=1/x\) about the \(x\)-axis on \([1,\infty)\). Find the volume and surface area of this solid. (This shape, as graphed in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\), is known as "Gabriel's Horn" since it looks like a very long horn that only a supernatural person, such as an angel, could play.)

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): A graph of Gabriel's Horn.

Solution

To compute the volume it is natural to use the Disk Method. We have:

\[\begin{align}V &= \pi\int_1^\infty \frac{1}{x^2}\ dx \\ &= \lim_{b\to\infty}\pi\int_1^b\frac{1}{x^2}\ dx \\ &= \lim_{b\to\infty} \left.\pi\left(\frac{-1}{x}\right)\right|_1^b \\ &= \lim_{b\to\infty} \pi\left(1-\frac1b\right) \\ &= \pi \ \text{units}^3.\end{align}\]

Gabriel's Horn has a finite volume of \(\pi\) cubic units. Since we have already seen that regions with infinite length can have a finite area, this is not too difficult to accept.

We now consider its surface area. The integral is straightforward to setup:

\[SA = 2\pi\int_1^\infty \frac{1}{x}\sqrt{1+1/x^4}\ dx.\]

Integrating this expression is not trivial. We can, however, compare it to other improper integrals. Since \(1< \sqrt{1+1/x^4} \) on \([1,\infty)\), we can state that

\[2\pi\int_1^\infty \frac{1}{x} dx <2\pi\int_1^\infty \frac{1}{x}\sqrt{1+1/x^4} dx .\]

By Key Idea 21, the improper integral on the left diverges. Since the integral on the right is larger, we conclude it also diverges, meaning Gabriel's Horn has infinite surface area.

Hence the "paradox": we can fill Gabriel's Horn with a finite amount of paint, but since it has infinite surface area, we can never paint it.

Somehow this paradox is striking when we think about it in terms of volume and area. However, we have seen a similar paradox before, as referenced above. We know that the area under the curve \(y=1/x^2\) on \([1,\infty)\) is finite, yet the shape has an infinite perimeter. Strange things can occur when we deal with the infinite.

A standard equation from physics is "Work = force \(\times\) distance", when the force applied is constant. In the next section we learn how to compute work when the force applied is variable.