1.3: Primes

- Page ID

- 131033

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Definition:

Prime Numbers - integers greater than \(1\) with exactly \(2\) positive divisors: \(1\) and itself.

Let \(n\) be a positive integer greater than \(1\). Then \(n\) is called a prime number if \(n\) has exactly two positive divisors, \(1\) and \(n.\)

Composite Numbers - integers greater than 1 which are not prime.

Note that: \(1\) is neither prime nor composite.

There are infinitely many primes, which was proved by Euclid in 100BC.

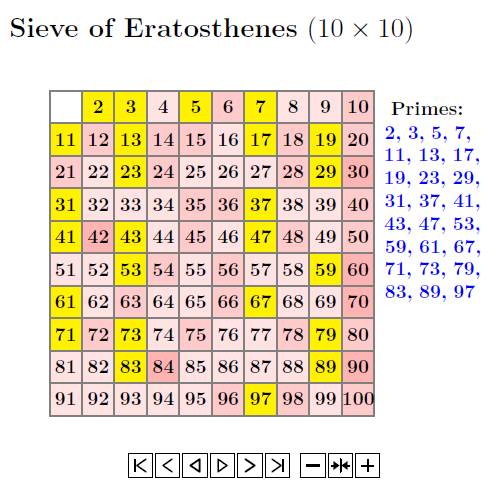

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Method of Sieve of Eratosthenes

Examples of prime numbers are \(2\) (this is the only even prime number), \(3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, \ldots\).

Method of Sieve of Eratosthenes:

The following will provide us a way to decide given number is prime.

Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Let \(n\) be a composite number with exactly \(3\) positive divisors. Then there exists a prime \(p\) such that \(n=p^2. \)

- Proof

-

Let \(n\) be a positive integer with exactly \(3\) positive divisors. Then two of the positive divisors are \(1\) and \(n.\)

Let \(d \) be the third positive divisor. Then \(1 < d < n \) and the only positive divisors of \(d\) are \(1 \) and \(d.\)

Therefore \(d\) is prime.

Since \(d \mid n\), \(n=md, m \in\mathbb{Z_+}\).

Since \(m \mid n\) and \(1 <m<n, m=d, n=d^2.\)

Thus, \(d \) is prime. \(\Box\)

Theorem \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Every composite number \(n\) has a prime divisor less than or equal to \(\sqrt{n}\). If \(p\) is a prime number and \(p \mid n\), then \(1<p \leq \sqrt{n}.\)

- Proof

-

Suppose \(p\) be the smallest prime divisor of \(n\). Then there exists an integer \(m\) such that \(n=pm\). Assume that \(p > \sqrt{n}\). Then \(m < \sqrt{n}.\)

Let \( q\) be any prime divisor of \(m\). Then \( q \) is also a prime divisor of \(n\) and \( q < m < \sqrt{n} < p.\) This is a contradiction.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\):

Is \(223\) a prime number?

Solution:

The prime numbers \(< \sqrt{223}\) are as follows: \(2, 3, 5, 7, 11,\) and \(13\). Note that \( 17^2 >223.\)

Since \(223\) is not divisible by any of the prime numbers identified above, \(223\) is a prime number.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Is \(2011\) a prime number?.

- Answer

-

yes.

Theorem \(\PageIndex{3}\): Prime divisibility theorem

Let \(p\) be a prime number. If \(p \mid ab, a,b \in \mathbb{Z}, \) then \(p\mid a\) or \(p\mid b\).

- Proof

-

Let \(p\) be a prime number and let \(a,b \in \mathbb{Z}.\) Assume that \(p \mid ab\). If \(p\mid a\), we are done. So we suppose that \(p\) does not divide \(a\). Thus \(gcd(a,p)=1.\) Thus there exists \(x,y \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(1=ax+py\). Hence \(b=abx+pby\). Since \(p \mid ab\), \(ab=pm, m\in \mathbb{Z}.\) Thus \(b=pmx+pby=p(mx+by).\) Hence, \(p\mid b.\)

Theorem \(\PageIndex{5}\)

There are infinitely many primes.

- Proof

-

Proof by contradiction.

Suppose there are finitely many primes \(p_1, p_2, ...,p_n\), where \(n\) is a positive integer. Consider the integer \(Q\) such that

\[Q=p_1p_2...p_n+1.\]

Notice that \(Q\) is not prime. Hence \(Q\) has at least a prime divisor, say \(q\). If we prove that \(q\) is not one of the primes listed then we obtain a contradiction. Suppose now that \(q=p_i\) for \(1\leq i\leq n\). Thus \(q\) divides \(p_1p_2...p_n\) and as a result \(q\) divides \(Q-p_1p_2...p_n\). Therefore \(q\) divides 1. But this is impossible since there is no prime that divides 1 and as a result \(q\) is not one of the primes listed.

The following theorem explains the gaps between prime numbers:

Theorem \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Let \(n\) be an integer. Then there exists \(n\) consecutive composite integers.

- Proof

-

Let \(n\) be an integer. Consider the sequence of integers \[(n+1)!+2, (n+1)!+3,...,(n+1)!+n, (n+1)!+(n+1)\]

Notice that every integer in the above sequence is composite because \(k\) divides \((n+1)!+k\) if \(2\leq k\leq (n+1)\).

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\):

Does there exist a block of \(1000000\) consecutive integers without a prime number among them?

Solution

Use \(1000001 !\) and consider \(1000001 ! +2 , \ldots, 1000001!+1000001\)

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\):

Consider the formula \(y=x^2+x+13\). Then

1. Find the values \(y\) for \( x=1, \cdots, 12\). How many of these values are prime?

2. Can we conclude that this formula always generates a prime number?

Definition: Twin primes

Two prime numbers are called twin primes if they differ by \(2\).

Theorem \(\PageIndex{6}\) Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic (FTA)

Let \(n \in\mathbb{Z_+}\), then n can be expressed as a product of primes in a unique way. This means

\(n=p_1^{n_1} p_2^{n_2} \cdots p_k^{n_k}\), where \(p_1 <p_2< ... <p_k\) are primes.

Neither the fundamental theorem nor the proof shows us how to find the prime factors. We can use tests for divisibility to find prime factors whenever possible.

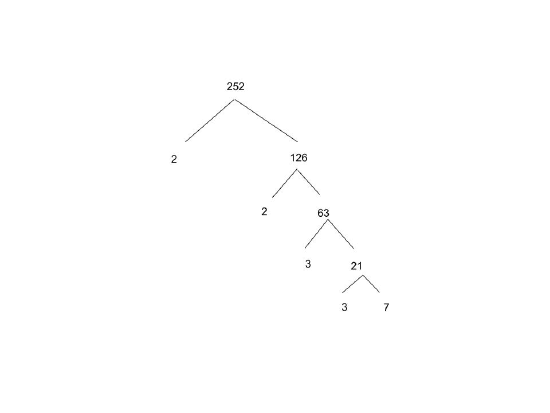

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\):

Find the prime factorization of

1. \(252\)

2.\(2018\).

3. \(1000\)

Solution

1. Using divisibility tests, we can find that \(252= 2^2 3^2 7\)

2. We can see that \(2018\) is divisible by 2, and \(2018= 2 \times 1009\). \(1009 \) is prime (why?).

3. \(1000=10^3=((2)(5))^3=2^3 5^3\)

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\):

Find the prime factorization of \(1000001\).

Solution

Consider \(1000001=1000000+1= 10^6+1=(10^2)^3+1^3= (10^2+1^2) (10^4-10^2+1^2)= 101 \times 9901 \). \(101\) and \(9901\) are prime (why?)

Determine \( gcd( 2^6 \times 3^9, 2^4 \times 3^8 \times 5^2)\) and \(lcm( 2^6 \times 3^9, 2^4 \times 3^8 \times 5^2)\).

Solution

\( gcd( 2^6 \times 3^9, 2^4 \times 3^8 \times 5^2)= 2^4 \times 3^8\) (the lowest powers of all prime factors that appear in both factorizations) and \(lcm( 2^6 \times 3^9, 2^4 \times 3^8 \times 5^2)= 2^6 \times 3^9 \times 5^2\) (the largest powers of each prime factors that appear in factorizations).

Note: Conjectures

Goldbach's Conjecture(1742)

Every even integer \(n >2\) is the sum of two primes.

Goldbach's Ternary Conjecture:

Every odd integer \(n \geq 5 \) is the sum of at most three primes.

Wilson's Theorem

Let \(p\) be a prime number. Then \((p - 1)! + 1\) is divisible by \(p\).

- Proof:

-

Consider the product \(P = 1 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdots (p-1)\). Now, let's pair each number \(k\) from \(1\) to \(p-1\) with its modular inverse \(k^{-1}\) modulo \(p\).

We know that for every \(k\) such that \(1 \leq k \leq p-1\), there exists a unique \(k^{-1}\) such that \(kk^{-1} \equiv 1 \pmod{p}\). Moreover, these pairs will be distinct because if \(kk^{-1} \equiv 1 \pmod{p}\) and \(jj^{-1} \equiv 1 \pmod{p}\) for \(k \neq j\), then \(k = kj^{-1}\) and \(j = jk^{-1}\), implying \(k = j\), which contradicts the distinctness of the pairs.

Thus, we can pair each \(k\) with \(k^{-1}\) such that the product of these pairs is congruent to \(1 \pmod{p}\). Therefore, \(P \equiv (p-1)! \equiv -1 \pmod{p}\). Adding \(1\) to both sides gives \((p-1)! + 1 \equiv 0 \pmod{p}\), which means \((p-1)! + 1\) is divisible by \(p\).

Fermat's Little Theorem

For any prime number \( p \) and any positive integer \( a \) such that \( p \) does not divide \( a \), we have \( a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \pmod{p} \).

Euler's Theorem

If \(a\) and \(n\) are relatively prime (i.e., \(\gcd(a, n) = 1\)), then \[ a^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \pmod{n} \]

The following results will help us find Euler's totient function\(\phi(n)\) for \(n\in \mathbb{N}\).

1. If \(p\) is prime then \(\phi(p)=p-1.\)

2. If \(p\) is prime and \(k\) is a positive integer then \(\phi(p^k)=p^k-p^{k-1}.\)

3. If \(m\) and \(n\) are relatively prime, then \(\phi(mn)=\phi(m)\phi(n).\)

4. \[ \phi(n) = n \times \prod_{p|n} \left(1 - \frac{1}{p}\right) \] where the product is taken over distinct prime factors \(p\) of \(n.\)

Find \(\phi(252)\).

Solution

Since \(252= 2^2 3^2 7\), \(\phi(252)=(2^2-2)(3^2-3)(7-1)=72\).