2.1: Introduction to Group

- Page ID

- 131036

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Let \(G\) be a non-empty set.

A binary operation, \(\star\), on \(G\) is defined as : \( a \star b\) for all \(a,b \in G.\)

A closed binary operation, \(\star\), on \(G\) is defined as a function: \(\star: G \times G \rightarrow G, \star(a,b)=a \star b \in G\).

Then \(G\) with the closed binary operation \(\star \), \((G,\star) \), is a group if all of the following conditions are satisfied:

-

Associative: \(a\star (b \star c)=(a \star b) \star c\); \(\forall a,b,c \in G\).

-

Identity: There exists an identity, \(e \in G\), s.t. \(e \star a=a \star e=a\).

-

Inverse: For each element \(a \in G\), there exists an element \(b \in G\) s.t. \(a\star b=b \star a=e\).

In other words, A group is a non-empty set associated with a binary operation that satisfies certain axioms. The operation must be closed, associative, and have an identity element. Additionally, every element must have an inverse.

Let \((G,\ast)\) be a group. Then \((G,\ast )\) is called an abelian group if \(a \star b=b \star a, \forall a, b \in G\). That is that the group satisfies the commutative property

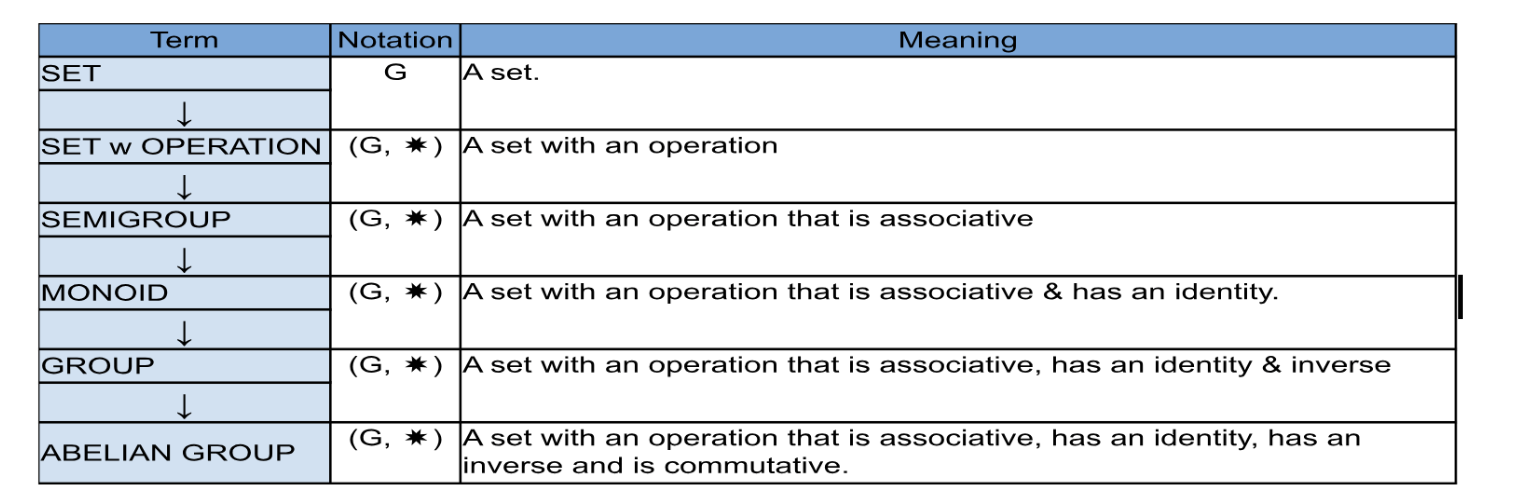

A summary of the terms is shown below.

The sets \( \mathbb{Z}, \mathbb{Q}, \mathbb{R}, \) and \( \mathbb{C} \) with addition \(+\) are groups with the identity of \(0\) and each element \(a\) an inverse \(-a.\)

\((\mathbb{Z}, \cdot)\) is a monoid, has no inverse, and is thus not a group. Why?

It's a set with an operation, is closed, is associative, and has an identity but does not have an inverse.

Counterexample:

\(2 \in \mathbb{Z}\), but there is no element \(b \in \mathbb{Z}\) s.t. \(2 \cdot b=1.\)

Let \( V \) be a vector space, then \((V, +)\) is an abelian group.

Let \(n\in \mathbb{Z}_+ \).

Let \(M_{nn} (\mathbb{R}) \) be the set of all \(n \times n\) matrices over \(\mathbb{R}\) then \((M_{nn} (\mathbb{R}) ,+)\) is an abelian group.

Let \(M_{nn} (\mathbb{C}) \) be the set of all \(n \times n\) matrices over \(\mathbb{C}\) then \((M_{nn} (\mathbb{C}), +)\) is an abelian group.

\( GL_2 (\mathbb{R})= \Big\{ A=\begin{bmatrix}a & b\\

c & d\end{bmatrix} \big| a,b,c,d \in \mathbb{R}, \det {(A)} =ad-bc \ne 0 \Big\} \) where \(GL_2(\mathbb{R})\) stands for General Linear Group that is a \(2 \times 2\) matrix.

Is \((GL_2(\mathbb{R}), \cdot)\) a group? Yes, but not an Abelian group.

\([A] \cdot ([B] \cdot [C]) = ([A] \cdot [B]) \cdot[C]\) is true, so we have associativity.

Every element \([A]\) in \( GL_2 (\mathbb{R})\) has an inverse since \(det(A)\ne 0\).

Since \(I \in GL_2 (\mathbb{R}), GL_2 (\mathbb{R})\) has an identity.

Matrix multiplication is not commutative since \([A] \cdot [B] \ne [B] \cdot [A]\).

Counterexample:

\(\begin{bmatrix}0 & 1\\

1& 0\end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\\

0& -1\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}0 & -1\\

1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\)

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0\\

0 & -1 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1\\

1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0\\

-1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\)

Notice that \(\begin{bmatrix}0 & 1\\

1& 0\end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\\

0& -1\end{bmatrix} \in GL_2({\mathbb{R}}). \)

Since \( \begin{bmatrix}0 & -1\\

1 & 0\end{bmatrix} \ne \begin{bmatrix}0 & 0\\

-1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\), \((GL_2(\mathbb{R}), \cdot)\) is not commutative.

Thus \((GL_2(\mathbb{R}), \cdot)\) is a group, but not an abelian group since it is not commutative.

Let \(n\in \mathbb{Z}_+ \).

\( GL_n (\mathbb{R})= \Big\{ A\in M_{nn}(\mathbb{R})| \det {(A)} \ne 0 \Big\} \), General Linear Group over \(\mathbb{R}\).

\( GL_n (\mathbb{C})= \Big\{ A\in M_{nn}(\mathbb{C})| \det {(A)} \ne 0 \Big\} \), General Linear Group over \(\mathbb{C}\).

Let \(SL_2(\mathbb{R})= \Big\{ A=\begin{bmatrix}a & b\\

c & d\end{bmatrix} \big| a,b,c,d \in \mathbb{R}, \det {(A)} =ad-bc = 1 \Big\}\), where \(SL_2(\mathbb{R})\) stands for Special Linear Group that is a \(2 \times 2\) matrix. Is \((SL_2(\mathbb{R}), \cdot)\) a group?

Proof:

Let \(A,B \in SL_2(\mathbb{R})\).

Then \(\det {(A)}=\det {(B)}=1\).

Consider \(\det{(AB)}= \det{(A)} \cdot \det{(B)}=(1)(1)=1\).

Hence \(AB \in SL_2(\mathbb{R})\).

Since matrix multiplication is associative, \((SL_2(\mathbb{R}), \cdot)\) is associative.

Since the \(2 \times 2\) matrix identity, \(I =\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\\

0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\in SL_2(\mathbb{R}),\) and \(AI=IA=A\) for all \(A\in SL_2(\mathbb{R})\), \((SL_2(\mathbb{R}), \cdot)\) has the identity.

Inverse:

Proof:

Let \(A \in SL_2(\mathbb{R})\).

Then \(\det{(A)}=1\), therefore \(A^{-1}\) exists.

Consider \(\det{(A^{-1})}= \frac{1}{\det{(A)}}=1\).

Therefore \(A^{-1} \in SL_2(\mathbb{R})\).

Hence \(SL_2(\mathbb{R})\) is a group, but not an abelian group.

Note that \(SL_2(\mathbb{R}) \subseteq GL_2(\mathbb{R})\).

If \((G, *)\) is a group, then

-

If \(|G|\) is finite, then \((G,*)\) is called a finite group.

-

If \(|G|\) is infinite, then \((G,*)\) is called an infinite group.

A Cayley table, named after the British mathematician Arthur Cayley, is a square table used in group theory to represent the binary operation of a finite group. It provides a concise way to display all possible combinations of group elements and the result of their operation.

Here are some examples of Cayley tables.

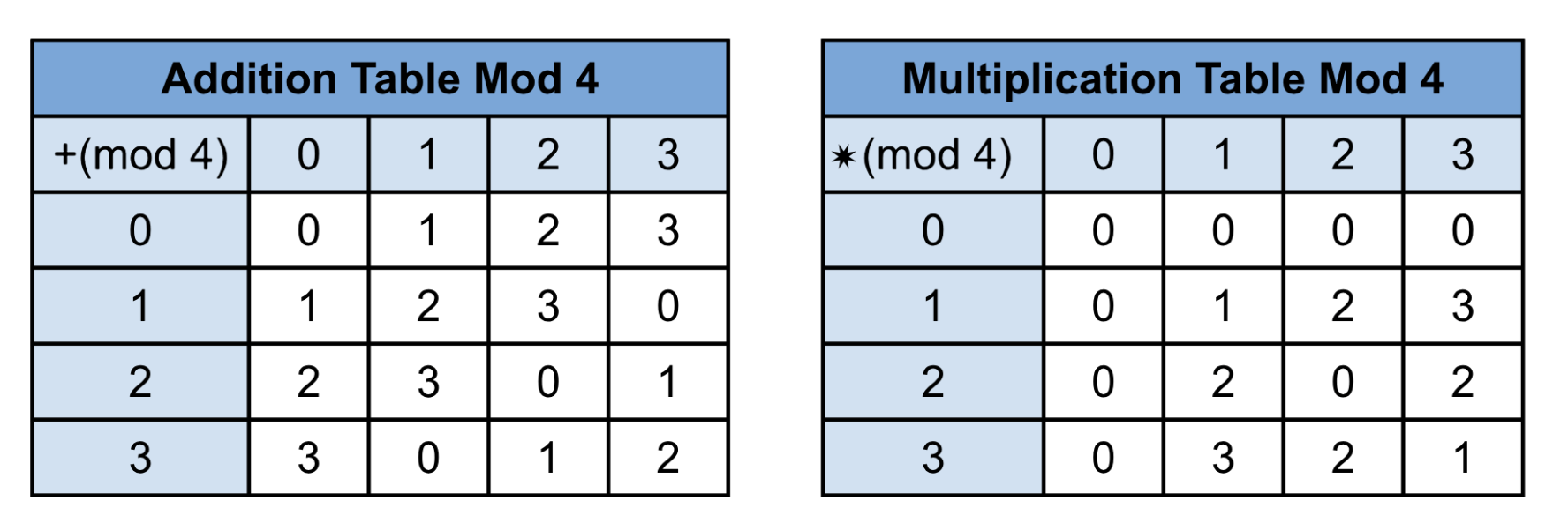

Define a relation on \(\mathbb{Z}\) by \( a R b\) iff \(a \equiv b \pmod{4} \), \(a,b \in \mathbb{Z},\) then \( R \) is an equivalence relation and the equivalence classes are \([0],[1],[2] \) and \([3] \). Another way to show the equivalence classes is to use the following notation: \(\mathbb{Z}_4=\{0,1,2,3\} \).

Cayley Tables for \(+\) and \(\cdot (mod 4)\) are shown below.

Note: The above tables are commutative; we can see them by noticing a mirror image along the diagonal.

\((\mathbb{Z}_4, +)\) is an abelian group. In fact, \((\mathbb{Z}_n, +)\) is an abelian group for every positive integer \(n\).

Note: In the case of multiplication, we must remove zero to make a group in many cases. We will denote \(\mathbb{Z}_n^*=\{1, 2, \cdots, n-1\}\) .

However, in the case of \((\mathbb{Z}_4^*,+) \) and \((\mathbb{Z}_4^*,\ast ) \) this would not make a group, since \(2+2=0 \pmod{4} \), \(2\cdot2=0 \pmod{4} \), but \(0 \notin \mathbb{Z}_4^* \).

\((\mathbb{Z}_n^*,\ast ) \) forms a group if \(n\) is prime.

|

Thinking Out Loud - Discussion of Modular Operations Let \(m \in \mathbb{Z}_+ \). If \(a \equiv b \pmod{m} \) and \(c \equiv d \pmod{m} \),then \(ac \equiv bd \pmod{m} \), \(a+c \equiv b+d \pmod{m} \), and \(a^n \equiv b^n \pmod{m} \). In terms of \(\pmod{m} \), we use \(\mathbb{Z}_m=\{0,1,2,3,\ldots\, m-1\} \). Note \((\mathbb{Z}_m, +\pmod{m}) \) is always an abelian group. Note \((\mathbb{Z}_m, \bullet \pmod{m}) \) is not always a group (need to remove zero and for \(m= \) a prime). If \((\mathbb{Z}_m^*, \bullet \pmod{m})\) is a group, then the group is abelian, since \(ab \equiv ba \pmod{m} \). |

Let \((G,\ast)\) be the set \(\{A, R, L, B\}\) where A stands for "attention," R stands for "turn right," L stands for "Turn Left," and B stands for "About Face." The Cayley table is shown below:

|

\(\ast\) |

A |

R |

L |

B |

|

A |

A |

R |

L |

B |

|

R |

R |

B |

A |

L |

|

L |

L |

A |

B |

R |

|

B |

B |

L |

R |

A |

Note that the multiplication table is same as \((\mathbb{Z}_4,+ \pmod{4})\). In this case, we say that this group isomorphic to \((\mathbb{Z}_4,+ \pmod{4})\).

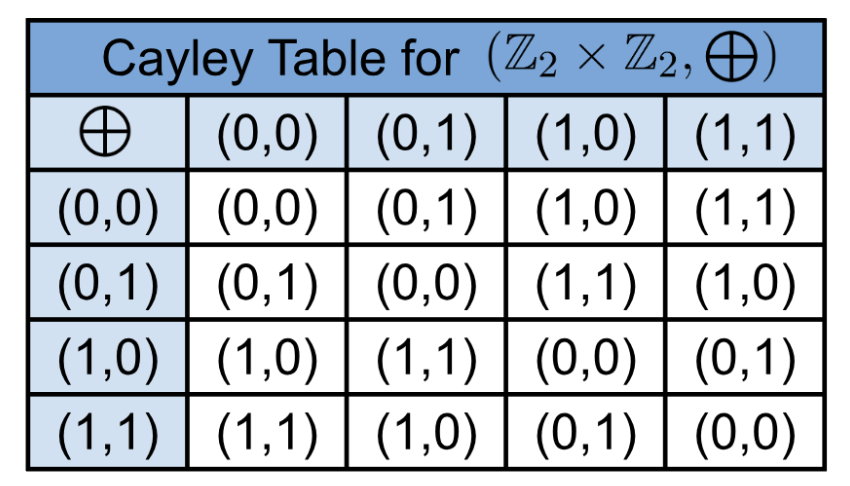

Is \((\mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2, \bigoplus)\) a group?

-

The product (in this case, component modulo 2) of any two elements is contained in the set.

-

The set and operation are associative since \(a \bigoplus (b \bigoplus c)= (a \bigoplus b) \bigoplus c) \forall a,b,c \in \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2\).

-

The SEMIGROUP has an identity since \(a\bigoplus e=e \bigoplus a =a, \forall a \in \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2\). The identity is \((0,0)\).

-

The semigroup has an inverse since \(\exists a,b \in \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2| a\bigoplus b=b \bigoplus a = e\). Look at \((0,1)\bigoplus(0,1)=(0,0)\), which is the identity. For proof, we would need to examine all cases.

-

The GROUP is also abelian since it is commutative (determined by seeing that the top diagonal matrix is the same as the bottom diagonal matrix).

-

The group is also finite since we could list all the elements.

Note: \((\mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2, \bigoplus)\) is called a Klein 4 \( (K_4) \) Group. This can be defined as \(K_4=\{e, a, b, c\}\) such that \(a^2=b^2=c^2=e\) with the product of any two distinct non-identity elements is the third: \(ab = c\), \(ac = b\), and \(bc = a\).

Quaternion Group:

\( 1 =\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\\

0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\), \( I =\begin{bmatrix}0 & 1\\

-1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\), \( J =\begin{bmatrix}0 & i\\

i & 0\end{bmatrix}\), \( K =\begin{bmatrix} i & 0\\

0 & -i \end{bmatrix}\), where \(i\) is the complex number such that \(i^2=-1.\)

Notation Notes:

\((\mathbb{Q}^*, \bullet)\): the * indicates that zero is eliminated. This is usually done to obtain an inverses.

\((\mathbb{Z}_n,+)\): The subscript indicates the operation is \(\pmod{n}\).

We will discuss these examples in detail later.

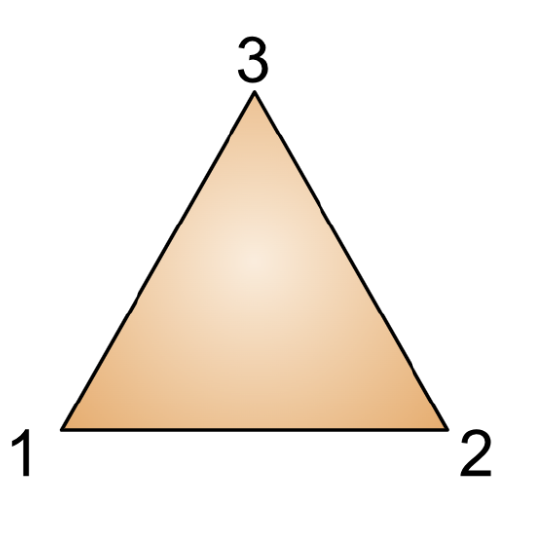

Example \(\PageIndex{11}\): Dihedral Group

Consider the equilateral triangle below. What rigid motions can we make to it that will result in the triangle occupying the same space? What happens if we combine rigid motions? Keep in mind that "doing nothing" is also a rigid motion.

Symmetries of equilateral triangles:

Let \(r\) be a rotation then there are three rotations \( I, r, r^2.\) Let \(s\) be a reflection, then there are \(s, rs, r^2s \) elements. In this case, \( r^3=s^2=I\) and \(sr=r^2s.\) Thus \(D_3=\{I,r,r^2,s, rs, r^2s \}.\)

Notation:

\(1 \equiv \begin{pmatrix}

1 & 2 & 3\\

1 & 2 & 3

\end{pmatrix}\) the identity matrix.

\((1,2) \equiv \begin{pmatrix}

1 & 2 & 3\\

2 & 1 & 3

\end{pmatrix}\). Note that 3 points to itself.

\((1,2,3) \equiv \begin{pmatrix}

1 & 2 & 3\\

2 & 3 & 1

\end{pmatrix}\).

\((1,3,2) \equiv \begin{pmatrix}

1 & 3 & 2\\

3 & 2 & 1

\end{pmatrix}\).

\(S_3= \{1,(1,2),(1,3), (2,3), (1,2,3),(1,3,2)\}\). This is the list of possible permutations of the above triangle in Example \(\PageIndex{11}\). Note that \((1,2,3)\) and \((3,2,1)\) are rotations, while \((1,2), (1,3),\) and \((2,3)\) are reflections around the missing angles bisection. \(|S_3|=3!=2\cdot 3=6\).

|

Cayley Table for \(S_3\) |

||||||

|

1 |

(1,2,3) |

(1,3) |

(1,2) |

(2,3) |

(1,3,2) |

|

|

1 |

1 |

(1,2,3) |

(1,3) |

(1,2) |

(2,3) |

(1,3,2) |

|

(1,2,3) |

(1,2,3) |

(1,3,2) |

(2,3) |

(1,3) |

(1,2) |

1 |

|

(1,3) |

(1,3) |

(1,2) |

1 |

(1,2,3) |

(1,3,2) |

(2,3) |

|

(1,2) |

(1,2) |

(2,3) |

(1,3,2) |

1 |

(1,2,3) |

(1,3) |

|

(2,3) |

(2,3) |

(1,3) |

(1,2,3) |

(1,3,2) |

1 |

(1,2) |

|

(1,3,2) |

(1,3,2) |

1 |

(1,2) |

(2,3) |

(1,3) |

(1,2,3) |

Notes: The operation goes from right to left. For example, the operation is \((1, 2,3)(1,3)=(2,3).\) In this case \((1,3)\) done first and then \((1,2,3)\).

\(S_3\) is a non-abelian group of order \(6\).

Let \(n\) be a positive integer.

Then define \(U(n)=\{a \in \mathbb{Z}_+| \gcd(a,n)=1\}.\) Then \((U(n), \cdot \mod n)\) is an abelian group. \(U(n)\) is a unitary group of order \(|\phi(n)|\) .

Summary:

|

Examples of Sets with Binary Operation \((G,\ast) \) have associative property, identity, and an inverse. |

|||

|

Examples |

↙ |

↘ |

Examples |

|

\(S_3\), \(Q_8\) |

Finite Group |

Infinite Group |

|

|

↓ |

↓ |

||

|

\((\{e\},*)\), \((\mathbb{Z}_n,+)\), \((\mathbb{Z}_p,\cdot)\), \((\mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2, \bigoplus)\), \(U(n)\) |

Abelian (commutative) |

Abelian (commutative) |

\((\mathbb{Z},+)\), \((\mathbb{Q},+)\), \((\mathbb{R},+)\), \((\mathbb{C},+)\),\(SL_n(\mathbb{R})=\{ M_n(\mathbb{R}) \big| \det {(M_n(\mathbb{R})} =1\}\), \( GL_n(\mathbb{R})=\{ M_n(\mathbb{R}) \big| \det {(M_n(\mathbb{R})} \ne 0 \}\),\( (\mathbb{Q}^*, \bullet)\), …. |

When referring to a group, we will denote \((G, \ast)\) as \(G\) and represent the operation as \(ab\) instead of \(a \ast b\) for simplicity and clarity.