2.4: Cyclic groups

- Page ID

- 131666

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Order of group element

Let \((G,\star)\) be a group.

Let \(a \in G\), then the order of an element \(a \in G\), denoted by \(|a|\), be the smallest positive integer \(n\) s.t. \(a^n=e\). If no such \(n\) exists, we say that the order is infinite.

Consider the group \(\mathbb{Z}_{10}\) with addition modulo \(10.\) What is the order of its elements?

Consider \(\mathbb{Z}_{10}=\{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9\}\). Note that \(\{0\}\) is the identity and its order is \(1. \)

|

element |

Order |

Calculations |

|

0 |

\(|\langle 0 \rangle |=1\) |

|

|

1 |

\(|\langle 1 \rangle |=10\) |

\(1^{10}\equiv 0 \pmod{10}\) |

|

2 |

\(|\langle 2 \rangle |=5\) |

\(2^{1}\equiv 2\pmod{10}\), \(2^2 \equiv 4 \pmod{10}\), \(2^{3}\equiv 6 \pmod{10}\), \(2^{4} \equiv 8 \pmod{10}\), and \(2^{5}\equiv 0 \pmod{10}\). |

|

3 |

\(|\langle 3 \rangle |=10\) |

\(3^1\equiv 3 \pmod{10}\), \(3^2\equiv 6 \pmod{10}\) , \(3^3\equiv 9 \pmod{10}\), \(3^4\equiv 2 \pmod{10}\), \(3^5\equiv 5 \pmod{10}\), \(3^6\equiv 8 \pmod{10}\), \(3^7\equiv 1 \pmod{10}\), \(3^8\equiv 4 \pmod{10}\), \(3^9\equiv 7 \pmod{10}\), and \(3^{10}\equiv 0 \pmod{10}\). |

|

4 |

\(|\langle 4 \rangle |=5\) |

\(4^1 \equiv 4 \pmod{10}\), \(4^2 \equiv 8 \pmod{10}\), \(4^3 \equiv 2 \pmod{10}\), \(4^4 \equiv 6 \pmod{10}\), and \(4^5 \equiv 0 \pmod{10}\). |

|

5 |

\(|\langle 5 \rangle |=2\) |

\(5^1 \equiv 5 \pmod{10}\), and \(5^2 \equiv 0 \pmod{10}\). |

|

6 |

\(|\langle 6 \rangle |=5\) |

\(6^1 \equiv 6 \pmod{10}\), \(6^2 \equiv 2 \pmod{10}\), \(6^3 \equiv 8 \pmod{10}\), \(6^4 \equiv 4 \pmod{10}\) and \(6^5 \equiv 0 \pmod{10}\). |

|

7 |

\(|\langle 7 \rangle |=10\) |

\(7^1 \equiv 7 \pmod{10}\), \(7^2 \equiv 4 \pmod{10}\), \(7^3 \equiv 1 \pmod{10}\), \(7^4 \equiv 8 \pmod{10}\), \(7^5 \equiv 5 \pmod{10}\), \(7^6 \equiv 2 \pmod{10}\), \(7^7 \equiv 9 \pmod{10}\), \(7^8 \equiv 6 \pmod{10}\), \(7^9 \equiv 3 \pmod{10}\), and \(7^{10} \equiv 0 \pmod{10}\). |

|

8 |

\(|\langle 8 \rangle |=5\) |

\(8^1 \equiv 8 \pmod{10}\), \(8^2 \equiv 6 \pmod{10}\), \(8^3 \equiv 4 \pmod{10}\), \(8^4 \equiv 2 \pmod{10}\), and \(8^5 \equiv 0 \pmod{10}\). |

|

9 |

\(|\langle 9 \rangle |=10\) |

\(9^1 \equiv 9 \pmod{10}\), \(9^2 \equiv 8 \pmod{10}\), \(9^3 \equiv 7 \pmod{10}\), \(9^4 \equiv 6 \pmod{10}\), \(9^5 \equiv 5 \pmod{10}\), \(9^6 \equiv 4 \pmod{10}\), \(9^7 \equiv 3 \pmod{10}\), \(9^8 \equiv 2 \pmod{10}\), \(9^9 \equiv 1 \pmod{10}\), and \(9^{10} \equiv 0 \pmod{10}\). |

The order of a group is the number of elements in the group.

The order of an element \(a \in G\), denoted by \(|a|\), be the smallest positive integer \(n\) s.t. \(a^n=e\).

Let \((G,\star)\) be a group.

Let \(X=\{x_1, x_2 \dots, x_n\}\) where \(x_1, x_2 \dots, x_n \in G\), then the subset of \(G\) generated by \(X\) denoted by \(\langle X \rangle \) is

\( \left\{x_1^{m_1} x_2^{m_2} \cdots x_n^{m_n} \mid m_1, m_2 \cdots, m_n \in \mathbb{Z} \right\}.\)

Let \((G,\star)\) be a group.

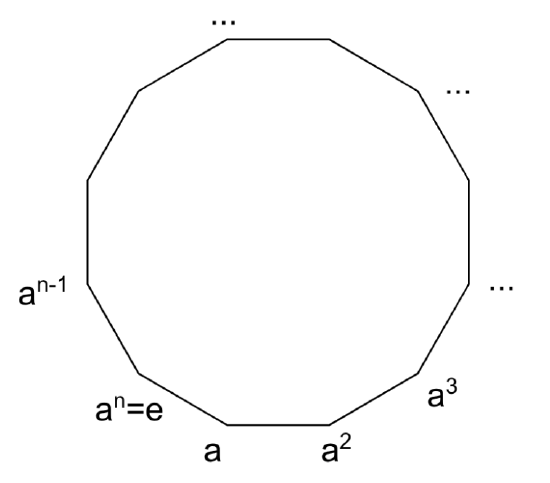

Let \(a \in G\), then define the set generated by \(a\) denoted by \(\langle a \rangle \) is \(\{a^m|m\in \mathbb{Z}\}=\{\cdots, a^{-2}, a^{-1}, e, a, a^2, \cdots\}\).

Note: \(a^0=e\).

Let \((G,\star)\) be a group.

Let \(a \in G\), then \(\langle a \rangle \) is the smallest subgroup of \(G\) that contains \(a\).

- Proof

-

Let \((G,\star)\) be a group. Let \(a \in G\). If \(a=e\) then \(\langle a \rangle =\{e\}\) is the smallest subgroup of \(G\) that contains \(e\).

Suppose \(a \ne e.\) Clearly \(e \in \langle a \rangle.\) Let \(g,h \in \langle a \rangle.\) Then \(g=a^m\) for some \(m\in \mathbb{Z}\) and \(h=a^n\) for some \(n \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Consider \(gh^{-1}=a^m \left(a^n\right)^{-1}=a^m a^{-n}=a^{m-n}.\) Since \(m-n \in \mathbb{Z}\), \(gh^{-1} \in \langle a \rangle.\)

Thus, \(\langle a \rangle \leq G.\) Suppose \(H\) is a subgroup of G that contains \(a\). Clearly, \(\langle a \rangle \leq H.\) \(\square\)

Let \((G,\star)\) be a group.

Let \(a \in G\), then \(\langle a \rangle \) is called cyclic subgroup of \( G.\)

If \( G=\langle a \rangle \) for some \(a \in G\), then \(G\) is called a cyclic group.

Remember the definition of a unitary group:

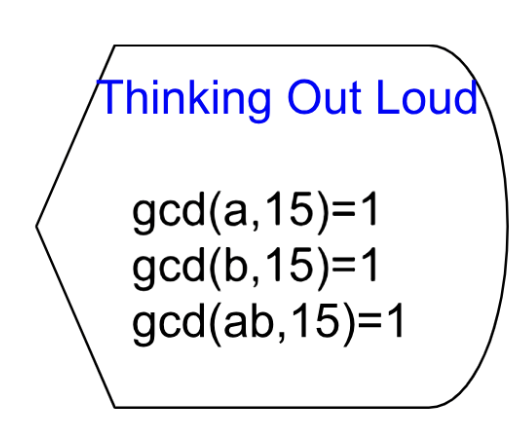

Let \(n\) be a positive integer. Then define \(U(n)=\{a \in \mathbb{Z}_+| \gcd(a,n)=1\}.\) Then \((U(n), \cdot \pmod n)\) is an abelian group. \(U(n)\) is a unitary group of order \(|\phi(n)|\) .

\(U(15)=\{1,2,4,7,8,11,13,14\}\) and \(\star= \cdot \pmod{15}\).

Let \(a \in U(15)\) and \(b \in U(15)\).

Then \(a(x)+15(y)=1\) and \(ab(x)+15by=b\) therefore \(U(15)\) is closed.

Since \(U(15)\) is a finite group, the order of the group is \(|U(15)|=8\).

However, \(U(15)\) is not a cyclic group.

Proof: (by exhaustion)

Let \(a \in U(15)\).

We will show that \(\not \exists a \in U(15)\), s.t. \(| \langle a \rangle |=8\).

\(|\langle1 \rangle |=1\) since \(1^1 \equiv 1 \pmod{15}\)

\(|\langle2 \rangle |=4\) since \(2^4 \equiv 1 \pmod{15}\)

\(|\langle4 \rangle |=2\) since \(4^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{15}\)

\(|\langle7 \rangle |=4\) since \(7^4 \equiv 1 \pmod{15}\).

\(|\langle8 \rangle |=4\) since \(8^4 \equiv 1 \pmod{15}\).

\(|\langle11 \rangle |=2\) since \(11^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{15}\).

\(|\langle13 \rangle |=4\) since \(13^4 \equiv 1 \pmod{15}\).

\(|\langle14 \rangle |=2\) since \(14^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{15}\).

Since \(\not \exists a \in U(15)\), s.t. \(|\langle a \rangle |=8\), \(U(15)\) is not a cyclic group.◻

Prove that \((U(14),(\cdot \pmod{14}))\) is cyclic.

Proof:

We will show that \(\exists a \in U(14)\) s.t. \(|\langle a \rangle |=|U(14)|\).

Consider \(U(14)=\{1,3,5,9,11,13\}\) where \(|U(14)|=6\).

Consider \(3^1\equiv 3 \pmod{14}\), \(3^2\equiv 9 \pmod{14}\), \(3^3 \equiv 13 \pmod{14}\), \(3^4\equiv 11 \pmod{14}\), \(3^5\equiv 5 \pmod{14}\) and \(3^6 \equiv 1 \pmod{14}\).

\(|\langle3 \rangle |=6\) since \(3^6 \equiv 1 \pmod{14}\).

Thus \(|\langle3 \rangle |=6\).

Therefore, \(U(14)\) is cyclic and \(3\) is a generator.◻

The following is an infinite cyclic group. Any infinite cyclic group is isomorphic to this group.

Is \((\mathbb{Z},+)\) cyclic group? If so, what are the possible generators?

Yes, \((\mathbb{Z},+)\) is a cyclic group that is generated by \(\pm 1\).

Proof of being a cyclic group:

Since the group generated by \(1\) contains \(1,\) the identity \(0,\) and the inverse of \(1, (-1),\) as well as all multiples of \(1 \) and \((-1)\), \((\mathbb{Z},+)\) is cyclic.

Possible Generators:

Note \(1^n\) is \(1+1+\cdots+1\) with \(n\) terms when \(n \rangle 0\) and \((-1)+(-1)+\cdots+(-1)\) with \(n\) terms when \(n\) is \(\langle0\).

We shall show \(\mathbb{Z}=\langle1 \rangle =\langle-1 \rangle \).

Consider that \(1^n\) means \(1+1+\cdots +1\) with \(n\) terms and that \(1^{-n}\) means \(+(-1)+(-1)+\cdots+(-1)\) with \(n\) terms.

It should be clear that \(1^n\) will generate \(\mathbb{Z}_+\) and that \(1^{-n}\) will generate \(\mathbb{Z}_-\). Note that \(1^0\) is interpreted as \(0\cdot 1=0\).

\(\langle1 \rangle =\{ \ldots, -3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,\ldots \}\).

Thus \(\langle1 \rangle \) is a generator of \((\mathbb{Z},+)\).

Similarly, we will show that \(\langle-1 \rangle \) is a generator of \((\mathbb{Z},+)\).

Consider that \((-1)^n\) means \(+(-1)+(-1)+\cdots+(-1)\) with \(n\) terms and that \(1^{-n}\) means \(1+1+\cdots +1\) with \(n\) terms.

It should be clear that \(1^n\) will generate \(\mathbb{Z}_-\) and that \(1^{-n}\) will generate \(\mathbb{Z}_+\). \(\langle-1 \rangle =\{ \ldots, -3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,\ldots \}\).

Thus the generators of \((\mathbb{Z},+)\) are \(\langle1 \rangle \) and \(\langle-1 \rangle \).

Properties:

Cyclic groups are abelian.

- Proof:

-

Let \((G,\star)\) be a group.

If \(G\) is cyclic, then \(G\) is abelian.

Assume that \(G\) is cyclic.

Then \(G=\langle g \rangle \) for some \(g \in G\).

Let \(a,b \in G\).

We will show \(ab=ba\).

Then \(a=g^m\) and \(b=g^n\), \(m,n \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Consider \begin{align*} ab &=g^mg^n\\&=g^{m+n}\\&=g^{n+m}\\&=g^ng^m\\&=ba. \end{align*}

Hence, \(G\) is abelian.◻

The converse is not true. Specifically, if a group is abelian, it is not necessarily cyclic. A counterexample is \((U(15), \bullet)\) since it is abelian but not cyclic.

Every subgroup of a cyclic group will be cyclic.

Let \((G, \star)\) be a cyclic group. If \(H \le G\), then \(H\) is a cyclic group.

- Proof

-

Let \(G=\langle g \rangle , \; g \in G\).

We will show \(H=\langle g^k \rangle \) for some \(k \in \mathbb{Z}\).

There are two cases to consider.

Case 1: \(H=\{e\}\)

Let \(H=\{e\}\), then we are done since \(e \star e=e\) thus \(|H|=|\langle e \rangle |=1\).

Case 2: \(H \ne \{e\}\)

Let \(H \ne \{e\}\).

Thus \(\exists h \in H\) s.t. \(h \ne e\).

Since \(h \in H\), \(h \in G\).

Hence \(h=g^m\) for some \(m \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Without loss of generality, we may assume \(m \in \mathbb{N}\).

Define \(S=\{n\in \mathbb{N}|g^n \in H\} \subseteq \mathbb{N}\).

Since \(S(\ne \{\})\) by the well ordering principle \(S\) has a smallest element \(k\).

We shall show that \(H=\langle g^k \rangle \).

Since \(g^k \in H\), \(\langle g^k \rangle \le H\).

Let \(h \in H\).

We shall show that \(h \in \langle g^k \rangle \).

Since \(h \in H\), \(h=g^m, m \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Since \(k,m \in \mathbb{Z}\), by the division algorithm, there exists \(q,r\) s.t. \(m=qk+r, \; 0\le r<k\).

Then \(g^m=g^{qk}g^r\) and \(g^{m-qk}=g^r\).

Since \(g^m, g^{qk} \in H\), then \(g^r \in H\).

Since \(k\) is the smallest, \(r=0\). (I think this is because \(g^0=e\))

Therefore \(g^m=(g^k)^q \in \langle g^k \rangle \).

Thus \(H \le \langle g^k \rangle \).◻

The Converse is not true. Every sub-group of the Klein 4-group is cyclic, but not the group.

Subgroups of \( (\mathbb{Z}, +)\) are of the form \((n\mathbb{Z},+)\), \(n\in \mathbb{N}\).

Let \(G\) be a cyclic group s.t. \(G=\langle a \rangle \) and \(|G|=n\).

Then \(a^k=e\) iff \(n|k\).

- Proof

-

Let \(G=\langle a \rangle \) with \(a^n=e\).

\(\langle a \rangle =\{e,a,a^2\ldots,a^{n-1}\}\).

Let \(a^k=e, \; k \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Since by the division algorithm, unique integers q and r exist such that \(k=nq+r, \; 0\le r< n, \; q,r \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Consider \(a^r=a^{k-nq}\)

\(=a^k(a^n)^{-q}\) Note: \(a^k=e\) is our assumption & \(n\) is the order of group.

\(=ee^{-q}\)

\(=e\).

Hence \(r=0\).

Hence \(r=0\).Thus \(k=nq\).

Therefore \(n|k\).

Conversely, assume that \(n|k\).

Then \(k=nm, m \in \mathbb{Z}\).

\(a^k=a^{nm}\).

\(=(a^n)^m\)

\(=e^m\)

\(=e\).

Hence the result.◻

Consider the group \(\mathbb{Z}_{12}\) with addition modulo \(12. \)

1. Is \((\mathbb{Z}_{12} ,+ mod (12) )\) cyclic group? If so, what are the possible generators? How many distinct generators are there? What can you say about the number of generators (hint: Euler totient number) and the possible generators (Hint: Divisors)?

3. Find all subgroups of \(\mathbb{Z}_{12}\) generated by each element. What are the orders of them? What can you say about these orders?

- Answer

-

1. Consider \(\mathbb{Z}_{12}=\{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11\}\) with addition modulo \(12. \) Note that \(\{0\}\) is the identity and its order is \(1. \)

Element

Order

Calculations

\(0\)

\(|\langle 0 \rangle |=1\)

\(1\)

\(|\langle 1 \rangle |=12\)

\(1^{12}\equiv 0 \pmod{12}\)

\(2\)

\(|\langle 2 \rangle |=6\)

\(2^{1}\equiv 2\pmod{12}\), \(2^2 \equiv 4 \pmod{12}\), \(2^{3}\equiv 6 \pmod{12}\), \(2^{4} \equiv 8 \pmod{12}\), \(2^{5}\equiv 10 \pmod{12}\) and \(2^{6}\equiv 0 \pmod{12}\).

\(3\)

\(|\langle 3 \rangle |=4\)

\(3^1\equiv 3 \pmod{12}\), \(3^2\equiv 6 \pmod{12}\) , \(3^3\equiv 9 \pmod{12}\), and \(3^4\equiv 0 \pmod{12}\).

\(4\)

\(|\langle 4 \rangle |=3\)

\(4^1 \equiv 4 \pmod{12}\), \(4^2 \equiv 8 \pmod{12}\), and \(4^3 \equiv 0 \pmod{12}\).

\(5\)

\(|\langle 5 \rangle |=12\)

\(5^1 \equiv 5 \pmod{12}\), \(5^2 \equiv 10 \pmod{12}\), \(5^3 \equiv 3 \pmod{12}\), \(5^4\equiv 8 \pmod{12}\), \(5^5 \equiv 1 \pmod{12}\), \(5^6 \equiv 6 \pmod{12}\), \(5^7 \equiv 11 \pmod{12}\), \(5^8 \equiv 4 \pmod{12}\),\(5^9 \equiv 9 \pmod{12}\), \(5^{10} \equiv 2 \pmod{12}\), \(5^{11} \equiv 7 \pmod{12}\), and \(5^{12} \equiv 0 \pmod{12}\).

\(6\)

\(|\langle 6 \rangle |=2\) \(6^1 \equiv 6 \pmod{12}\), and \(6^2 \equiv 2 \pmod{12}\).

\(7\)

\(|\langle 7 \rangle |=12\)

\(7^1 \equiv 7 \pmod{12}\), \(7^2 \equiv 2 \pmod{12}\), \(7^3 \equiv 9 \pmod{12}\), \(7^4 \equiv 4 \pmod{12}\), \(7^5 \equiv 11 \pmod{12}\), \(7^6 \equiv 6 \pmod{12}\), \(7^7 \equiv 1 \pmod{12}\), \(7^8 \equiv 8 \pmod{12}\), \(7^9 \equiv 3 \pmod{12}\), \(7^{10} \equiv 10 \pmod{12}\), \(7^{11} \equiv 5 \pmod{12}\), and \(7^{12} \equiv 0 \pmod{12}\).

\(8\)

\(|\langle 8 \rangle |=3\)

\(8^1 \equiv 8 \pmod{12}\), \(8^2 \equiv 4 \pmod{12}\) and \(8^3 \equiv 0 \pmod{12}\).

\(9\)

\(|\langle 9 \rangle |=4\)

\(9^1 \equiv 9 \pmod{12}\), \(9^2 \equiv 6 \pmod{12}\), \(9^3 \equiv 3 \pmod{12}\) and \(9^4 \equiv 0 \pmod{12}\).

\(9^5 \equiv 5 \pmod{10}\), \(9^6 \equiv 4 \pmod{10}\), \(9^7 \equiv 3 \pmod{10}\), \(9^8 \equiv 2 \pmod{10}\), \(9^9 \equiv 1 \pmod{10}\), and \(9^{10} \equiv 0 \pmod{10}\).

\(10\) \(|\langle 10 \rangle |=6\) \(10^1 \equiv 10 \pmod{12}\), \(10^2 \equiv 8 \pmod{12}\), \(10^3 \equiv 6 \pmod{12}\), \(10^4 \equiv 4 \pmod{12}\), \(10^5 \equiv 2 \pmod{12}\) and \(10^6 \equiv 0 \pmod{12}\).

\(11\) \(|\langle 11 \rangle |=12\) \(11^1 \equiv 11 \pmod{12}\), \(11^2 \equiv 10 \pmod{12}\), \(11^3 \equiv 9 \pmod{12}\), \(11^4 \equiv 8 \pmod{12}\), \(11^5 \equiv 7 \pmod{12}\), \(11^6 \equiv 6 \pmod{12}\), \(11^7 \equiv 5 \pmod{12}\), \(11^8 \equiv 4 \pmod{12}\), \(11^9 \equiv 3 \pmod{12}\), \(11^{10} \equiv 2 \pmod{12}\), \(11^{11} \equiv 1 \pmod{12}\), and \(11^{12} \equiv 0 \pmod{12}\). From the table, \((\mathbb{Z}_{12},+ mod (12) )\) is a cyclic group, the set of all possible generators are \(\{1, 5, 7, 11\}=\{ a \in \mathbb{Z}| gcd(a,12)=1 ,\; 1 \leq a < 12 \} \). Hence, the number of generators is the same as the number of integers relatively prime to \(12=2^2\,3\). That is, the number of generators is the Euler totient number \( \phi(12) =(2^2-2)(3^1-1)= 4 \;\; .\)

2. From the above table, we see that the orders of the subgroups are \(1, 2, 3, 4, 6\) and 12, which are all divisors of the order of \(\mathbb{Z}_{12}\). Specifically, the order of the subgroup generated by \(g \in \mathbb{Z}_{12}\) is \(\dfrac{n}{ gcd(g, n)}.\)

Note that \(12=2^2 \, 3\). Then the cyclic subgroups are \(\langle 1 \rangle , \langle 6 \rangle , \langle 4 \rangle , \langle 3 \rangle , \langle 2 \rangle , \langle 0 \rangle \) with orders \(12, 2, 3, 4, 6\) and \(1.\)

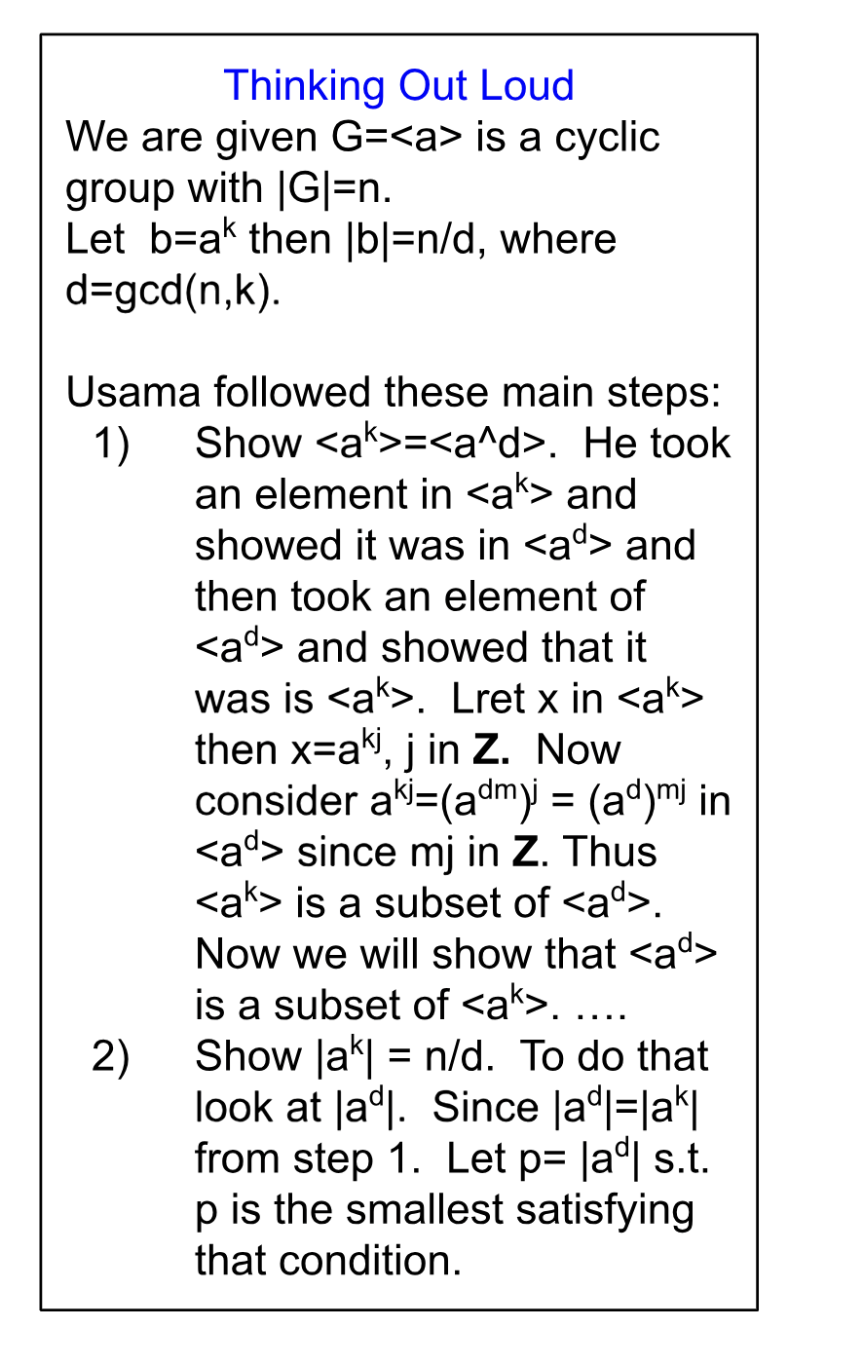

\(\langle a^k \rangle =\langle a^{\gcd(n,k)} \rangle \)

Let \(G=\langle a \rangle \) be a cyclic group with \(|G|=n\).

Let \(b \in G\).

If \(b=a^k\) then \(|b|=\frac{n}{d}, \; d=\gcd(k,n)\).

- Answer

-

Let \(G=\langle a \rangle \) with \(|G|=n\) and \(a \in G\).

Let \(a^n=e\).

We will show that \(\langle a^k \rangle =\langle a^{\gcd{(n,k)}} \rangle \).

Let \(x \in \langle a^k \rangle \).

Since \(\gcd(n,k)=d\) for some \(d \in \mathbb{Z}_+\), \(d|n\) and \(d|k\).

Thus, \( k=md, m\in \mathbb{Z}\).

Consider an arbitrary power of \(a^k\), \((a^k)^j \in \langle a^k \rangle \).

\((a^k)^j = (a^{md})^j=(a^d)^{jm} \in \langle a^d \rangle \in \langle a^{\gcd{(n,k)}} \rangle \).

Let \(d=xn+yk, \; n,k \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Using the division algorithm, \((a^{xn+yk})^h= (a^n)^{xh} (a^k)^{yh}, \;n,k,h \in \mathbb{Z}\)

\(=(a^k)^{yh} \in \langle a^k \rangle \).

Thus \(a^k = a^d\).

Now we want to show \(|a^k|=\frac{n}{d}\).

Consider \((a^k)^{\frac{n}{d}}=(a^n)^{\frac{k}{d}}=e^{\frac{k}{d}}=e\).

Thus \(|a^k|\le \frac{n}{d}\).

Now consider \((a^d)^{\frac{n}{d}}=(a^n)=e \; \Rightarrow \; |a^d| \le \frac{n}{d}\).

Now consider \(0 \le i <\frac{n}{d}\).

Thus \( di< n\), where \(d\) is positive since it is the greatest common denominator.

Thus \((a^d)^i=a^{di}\ne e\) for \(di<n\).

Then we can show \(|a^d|=\frac{n}{d}\).

Consider \(|a^k|=|\langle a^k \rangle |=|\langle a^d \rangle |=|a^d|= \frac{n}{d}\).

Hence \(|a^k|=\frac{n}{d}\).

Let \(G=\langle g \rangle \) be a cyclic group with \(|g|=n\). Then \(G=\langle g^k \rangle \) if and only if \(gcd(k,n)=1.\)

- Proof

-

Let \(G=\langle g \rangle \) be a cyclic group with \(|g|=n\). Then

\( g \in G \) and \(g^n=e\).Assume that \( G = \langle g^k \rangle \). Then \( g = (g^k)^ x \) for some \( x \in \mathbb{Z} \).

Thus,

\(

g^{1 - kx} = e.

\)

By Theorem 2.4.5, \( n \mid (1 - kx) \). Therefore,

\(1 - kx = ny, \) for some \(y \in \mathbb{Z}.

\)

Which implies,

\(

1 = kx + ny,

\)

hence,

\(

\gcd(k, n) = 1.

\)Conversly, we shall show that if \( \gcd(k, n) = 1 \), then \( G = \langle g^k \rangle \).

Suppose that \( \gcd(k, n) = 1 \). Then

\(kx + ny = 1\), for some \( x, y \in \mathbb{Z}.\)

By using the properties of powers in a group and \(g^n=e\), we get,

\[

g^1 = g^{kx + ny}=(g^k)^x (g^n)^y=(g^k)^x.

\]Hence \( g \in \langle g^k \rangle \).

Therefore, we have \( G \subseteq \langle g^k \rangle \). Since \( \langle g^k \rangle \ \subseteq G\),

\(

G = \langle g^k \rangle.

\)

Let \(G=\langle a \rangle \) be a cyclic group with \(|G|=n\). Prove the following statements:

a) If \(H\leq G\) then \(H=\langle a^k \rangle \) for some integer \(k\) that divides \(n\).

b) If \(k|n\) then \(\langle a^{\frac{n}{k}} \rangle\) is the unique subgroup of \(G\) of order \(k\).

- Proof

-

a) Let \(G = \langle a \rangle\) with \(|G| = n.\) Assume that \(H\leq G\). By Theorem 2.4.3, \(H\) is cyclic. Hence \( H=\langle a^k \rangle\) for some integer \(k \in \textbf{Z}. \) Let \(d=gcd(k,n)\). We shall show that \( H=\langle a^d \rangle\). Since \(d=gcd(k,n)\), \(kx + ny = d\), for some \( x, y \in \mathbb{Z}.\) Consider, \[

a^d = a^{kx + ny}=(a^k)^x (a^n)^y=(a^k)^x.

\] Thus \(a^d \in H\). Therefore \(\langle a^d \rangle \subseteq H.\)

Since \(d|k, k=md,\) for some \( m\in \mathbb{Z}.\) Thus, \(a^k=a^{md}=\left(a^d\right)^m.\) Hence \( H \subseteq \langle a^d \rangle \). Thus \( H =\langle a^d \rangle\) and \(d|n.\)b) Let \(G = \langle a \rangle\) with \(|G| = n.\) Assume that \(k|n\). Suppose \(K\) be subgroup of \(G\) of order \(k\). We shall show that \(K=\langle a^{\frac{n}{k}} \rangle\). Since \(K\) is a subgroup of \(G\), \(K=\langle a^m \rangle\), for some, \( m \in \mathbb{Z}.\) By part a, \(m|n.\) Then \(\left(a^m\right)^{n/m}=e\). We shall show that \(\dfrac{n}{m}\) is the smallest positive integer with this property.

Now, \(|K|= \dfrac{n}{m}=k\). Thus, \(m=\dfrac{n}{k}\). Thus \(K= \langle a^\frac{n}{k} \rangle\) which is unique.

A group of prime order is cyclic.

- Proof

-

Let \(G\) be a group s.t. \(|G|=p\), where \(p\) is a prime number.

Let \(g \in G\) s.t. \(H=\langle g \rangle \) is a subgroup of \(G\).Since \(p > 1\), \(g \ne \{e\}\).

Since \(H\) is cyclic, \(\exists \; g^k=e\), for some \( k \in \mathbb{Z}\).

By the division algorithm, \(k=nq+r\) where \(0 \le r < n\).

Hence, \(e=g^k=g^{nq+r}=g^{nq}g^r=eg^r=g^r\).

Since the smallest positive integer \(k\) such that \(g^k=e\) is \(n\), \(r=0\). Thus \(n|k\).

Conversely, if \(n|k\), then \(k=nm\), \(m \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Consequently, \(g^k=g^{nm}=(g^n)^m=e^m=e\).

Thus, \(|\langle g \rangle |\) divides \(|G|\).

Consider that the only two divisors of a prime number are the prime number itself and 1.

Since \(p < 1\), \(|G|=p\).

Since \(|G|=p\), \(G\) is cyclic.◻

List all the cyclic subgroups of \(U(30)\).

\(U(30)=\{1,7,11,13,17,19,23,29\}\) and \(|U(30)|=8\).

|

\(k\) |

Calculations |

\(|k|\) |

|

7 |

\(7^1 \equiv 7 \pmod{30}\), \(7^2 \equiv 19 \pmod{30}\), \(7^3 \equiv 13 \pmod{30}\), \(7^4 \equiv 1 \pmod{30}\) |

4 |

|

11 |

\(11^1 \equiv 11 \pmod{30}\), \(11^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{30}\) |

2 |

|

13 |

\(13^1 \equiv 13 \pmod{30}\), \(13^2 \equiv 19 \pmod{30}\), \(13^3 \equiv 7 \pmod{30}\), \(13^4 \equiv 1 \pmod{30}\) |

4 |

|

17 |

\(17^1 \equiv 17 \pmod{30}\), \(17^2 \equiv 19 \pmod{30}\), \(17^3 \equiv 23 \pmod{30}\), \(17^4 \equiv 1 \pmod{30}\) |

4 |

|

19 |

\(19^1 \equiv 19 \pmod{30}\), \(19^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{30}\) |

2 |

|

23 |

\(23^1 \equiv 23 \pmod{30}\), \(23^2 \equiv 19 \pmod{30}\), \(23^3 \equiv 17 \pmod{30}\), \(23^4 \equiv 1 \pmod{30}\) |

4 |

|

29 |

\(29^1 \equiv 29 \pmod{30}\), \(29^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{30}\) |

2 |

Since \(\not \exists a \in U(30)\) s.t. \(|\langle a \rangle |=|U(30)|=8\), \(U(30)\) is not a cyclic group.

However the following subgroups of \(U(30)\) are cyclic: \(\{1,7,13,19\}\), \(\{1,17,19,23\}\), \(\{1,11\}\), \( \{1,19\} \), \(\{1,29\}\) and \(\{1\}\).

Let \(n \geq 1.\) Then \(U(n)\) is cyclic iff \(n=1, 2, 4, p^k\) or \(2p^k\) where \(p\) is an odd prime and \(k \geq 1.\)

\(U(n)\) is not cyclic if \(n\) is divisible by two distinct odd primes or by \(4\) and an odd prime.

\(U(1), U(2), U(3), U(4), U(5), U(6), U(7), U(9), U(10), U(11), U(18), U(27)\) are cyclic.

\(U(8), U(16), U(20), U(30)\) are not cyclic.