2.2: Equivalence Relations, and Partial order

- Page ID

- 7443

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Definition: Equivalence Relation

A binary relation is an equivalence relation on a nonempty set \(S\) if and only if the relation is reflexive(R), symmetric(S) and transitive(T).

Definition: Partial Order

A binary relation is a partial order if and only if the relation is reflexive(R), antisymmetric(A) and transitive(T).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): \(=\)

Let \(S=\mathbb{R}\). Define a relation \(R\) on \(S\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a=b.\) Is the relation \(R\) on \(S\),

a) reflexive, b) symmetric, c) antisymmetric, d) transitive, e) an equivalence relation, f) a partial order.

Solution:

-

\(R\) is reflexive.

Proof:

Let \(a \in \mathbb{R}\). Since \(a=a\), \(R\) is reflexive.◻

2. \(R\) is symmetric.

Proof:

Let \(a,b \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(a R b.\) Now, \( a=b \implies b=a\). Thus \(b R a.\) Hence \(R\) is symmetric.◻

3. \(R\) is antisymmetric.

Proof:

Proof:

Proof:

Since is reflexive, symmetric and transitive, it is an equivalence relation.

Proof:

is a partial order, since

is reflexive, antisymmetric and transitive.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Less than or equal to

Let and

be

. Is the relation a) reflexive, b) symmetric, c) antisymmetric, d) transitive, e) an equivalence relation, f) a partial order.

Solution

Proof:

Counterexample:

It is true that , but it is not true that

.

Proof:

We will show that given and

that

.

Proof:

We will show that given and

that

.

5. No, is not an equivalence relation on

since it is not symmetric.

6. Yes, is a partial order on

since it is reflexive, antisymmetric and transitive.

Definition: Equivalence Class

Given an equivalence relation \( R \) over a set \( S, \) for any \(a \in S \) the equivalence class of a is the set \( [a]_R =\{ b \in S \mid a R b \} \), that is

\([a]_R \) is the set of all elements of S that are related to \(a\).

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Equivalence relation

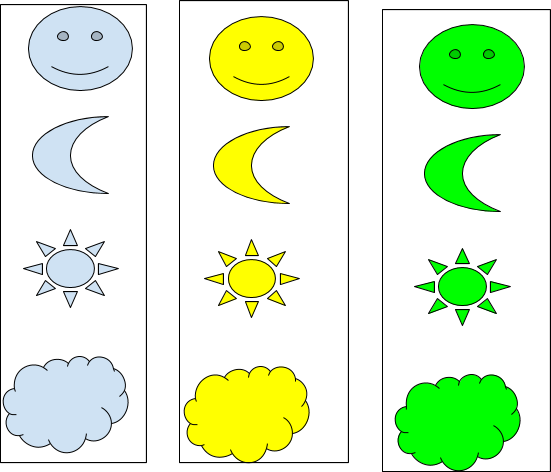

Define a relation that two shapes are related iff they are the same color. Is this relation an equivalence relation?

Equivalence classes are:

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\):

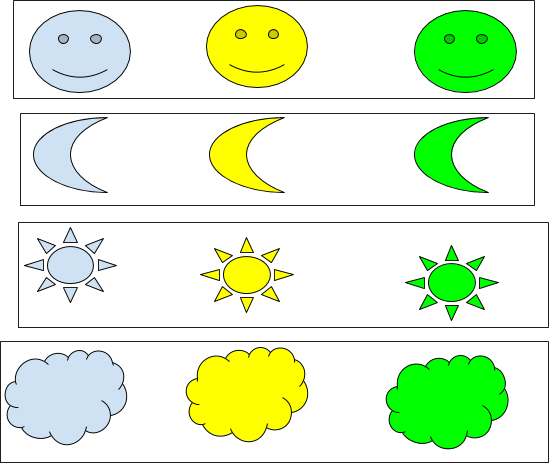

Define a relation that two shapes are related iff they are similar. Is this relation an equivalence relation?

Equivalence classes are:

Let \(A\) be a nonempty set. A partition of \(A\) is a set of nonempty pairwise disjoint sets whose union is A.

Note

For every equivalence relation over a nonempty set \(S\), \(S\) has a partition.

Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\)

If \( \sim \) is an equivalence relation over a non-empty set \(S\). Then the set of all equivalence classes is denoted by \(\{[a]_{\sim}| a \in S\}\) forms a partition of \(S\).

This means

1. Either \([a] \cap [b] = \emptyset\) or \([a]=[b]\), for all \(a,b\in S\).

2. \(S= \cup_{a \in S} [a]\).

- Proof

-

Assume

is an equivalence relation on a nonempty set

.

Let

. If

, then we are done. Otherwise,

Let

be the common element between them.

Then

and

, which means that

and

.

Since

is an equivalence relation and

.

Since

and

(due to transitive property),

.

For the following examples, determine whether or not each of the following binary relations on the given set

is reflexive, symmetric, antisymmetric, or transitive. If a relation has a certain property, prove this is so; otherwise, provide a counterexample to show that it does not. If

is an equivalence relation, describe the equivalence classes of

.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\):

Let \(S = \{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9\}\). Define a relation \(R\) on \(A = S \times S \) by \((a, b) R (c, d)\) if and only if \(10a + b \leq 10c + d.\)

Solution

Proof:

Counter Example:

Since ,

is not symmetric on

.◻

Proof:

Thus is antisymmetric on

.◻

5. is transitive on .

Proof:

6. is not an equivalence relation since it is not reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\):

Let . Define a relation

on

, by

if and only if

Solution

Proof:

Clearly since

and a negative integer multiplied by a negative integer is a positive integer in

.

Since ,

is reflexive on

.◻

2. is symmetric on

.

Proof:

Counter Example:

Since ,

is not antisymmetric on

.◻

Proof:

There are two cases to be examined:

Since in both possible cases

is transitive on

.◻

5. Since is reflexive, symmetric and transitive, it is an equivalence relation. Equivalence classes are

and

.

Note this is a partition since or

. So we have all the intersections are empty.

Further, we have . Note that

is excluded from

.

Hasse Diagram

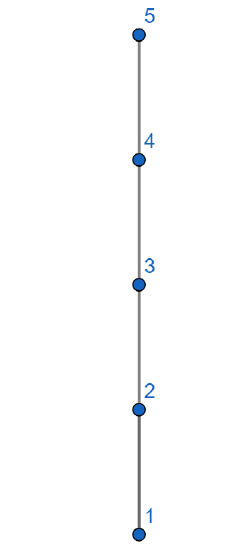

Consider the set \( S=\{1,2,3,4,5\}\). Then the relation \(\leq\) is a partial order on \(S\). Check!

Partial orders are often pictured using the Hasse diagram, named after mathematician Helmut Hasse (1898-1979).

Definition: Hasse Diagram

Let S be a nonempty set and let \(R\) be a partial order relation on \(S\). Then Hasse diagram construction is as follows:

- there is a vertex (denoted by dots) associated with every element of \(S\).

- if \( a R b\) , then the vertex \(b\) is positioned higher than vertex \(a\).

- if \( a R b\) and there is no \(c\) such that \(a R c\) and \(c R b\), then a line is drawn from a to b.

This diagram is called the Hasse diagram.

Hasse diagram for \( S=\{1,2,3,4,5\}\) with the relation \(\leq\).

Solution

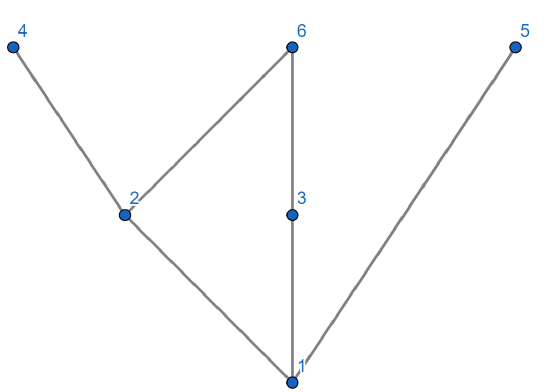

Show that \( \mathbb{Z}_+ \) with the relation \( | \) is a partial order. Draw a Hasse diagram for \( S=\{1,2,3,4,5,6\}\) with the relation \( | \).

Solution