20.2: Equations involving trigonometric functions

- Page ID

- 49081

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The previous section showed how to solve the basic trigonometric equations

\[\sin(x)=c, \quad \cos(x)=c, \quad \text{ and }\quad \tan(x)=c \nonumber \]

The next examples can be reduced to these basic equations.

Solve for \(x\).

- \(2\sin(x)-1=0\)

- \(\sec(x)=-\sqrt{2}\)

- \(7\cot(x)+3=0\)

Solution

- Solving for \(\sin(x)\), we get

\[2\sin(x)-1=0 \stackrel{(+1)}\implies 2\sin(x)=1 \stackrel{(\div 2)}\implies \sin(x)=\dfrac{1}{2} \nonumber \]

One solution of \(\sin(x)=\dfrac 1 2\) is \(\sin^{-1}\left(\dfrac 1 2\right)=\dfrac {\pi}{6}\). The general solution is

\[x=(-1)^n\cdot \dfrac{\pi}{6}+n\pi, \quad \text{ where } n=0,\pm1,\pm2, \dots \nonumber \]

- Recall that \(\sec(x)=\dfrac{1}{\cos(x)}\). Therefore,

\[\sec(x)=-\sqrt{2} \implies \dfrac{1}{\cos(x)}=-\sqrt{2} \quad\stackrel{(\text{reciprocal})} \implies\quad \cos(x)=-\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}=-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \nonumber \]

A special solution of \(\cos(x)=-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) is

\[\cos^{-1}\left(-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)=\pi-\cos^{-1}\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)=\pi-\dfrac{\pi}{4}=\dfrac{4\pi-\pi}{4}=\dfrac{3\pi}{4} \nonumber \]

The general solution is

\[x=\pm\dfrac{3\pi}{4}+2n\pi, \quad \text{ where } n=0,\pm1,\pm2, \dots \nonumber \]

- Recall that \(\cot(x)=\dfrac 1 {\tan(x)}\). So

\[\begin{aligned} 7\cot(x)+3=0 &\stackrel{(-3)}\implies & 7\cot(x)=-3 \stackrel{(\div 7)}\implies \cot(x)=-\dfrac{3}{7} \\ &\implies & \dfrac 1 {\tan(x)}=-\dfrac{3}{7} \quad \stackrel{(\text{reciprocal})} \implies\quad \tan(x)=-\dfrac{7}{3} \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

The solution is

\[x=\tan^{-1}\left(-\dfrac{7}{3}\right)+n\pi \approx -1.166+n\pi, \quad \text{ where } n=0,\pm1,\pm2,\dots \nonumber \]

For some of the more advanced problems it can be helpful to substitute \(u\) for a trigonometric expression first, then solve for \(u\), and finally apply the rules from the previous section to solve for the wanted variable. This method is used in the next example.

Solve for \(x\).

- \(\tan^2(x)+2\tan(x)+1=0\)

- \(2\cos^2(x)-1=0\)

Solution

- Substituting \(u=\tan(x)\), we have to solve the equation

\[u^2+2u+1=0 \stackrel{(\text{factor})}\implies (u+1)(u+1)=0 \implies u+1=0 \stackrel{(-1)}\implies u=-1 \nonumber \]

Resubstituting \(u=\tan(x)\), we have to solve \(\tan(x)=-1\). Using the fact that \(\tan^{-1}(-1)=-\tan^{-1}(1)=-\dfrac{\pi}{4}\), we have the general solution

\[x=-\dfrac{\pi}{4}+n\pi, \quad \text{ where } n=0,\pm1,\pm2, \dots \nonumber \]

- We substitute \(u=\cos(x)\), then we have

\[\begin{aligned} 2u^2-1=0 & \stackrel{(+1)}\implies & 2u^2=1 \quad \stackrel{(\div 2)}\implies \quad u^2=\dfrac 1 2 \\ & \implies & u=\pm\sqrt{\dfrac{1}{2}}=\pm\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}=\pm\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \\ & \implies & u=+\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \quad\text{ or }\quad u=-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

For each of the two cases we need to solve the corresponding equation after replacing \(u=\cos(x)\).

\[\begin{aligned}

\cos (x)&=\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \\

\text { with } \cos ^{-1}\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)&=\dfrac{\pi}{4} \\

\Longrightarrow x&=\pm \dfrac{\pi}{4}+2 n \pi & \text { where } n=0, \pm 1, \pm 2, \ldots

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

\[\begin{aligned}

\cos (x)&=-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \\

&\text { with } \begin{aligned}

\cos ^{-1}\left(-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right) &=\pi-\cos ^{-1}\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right) \\

&=\pi-\dfrac{\pi}{4}=\dfrac{3 \pi}{4}

\end{aligned} \\

\Longrightarrow x&=\pm \dfrac{3 \pi}{4}+2 n \pi \\

& \text { where } n=0, \pm 1, \pm 2, \ldots

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Thus, the general solution is

\[x=\pm\dfrac{\pi}{4}+2n\pi,\quad \text{ or } \quad x=\pm\dfrac{3\pi}{4}+2n\pi, \quad \text{ where } n=0,\pm1, \pm2,\dots \nonumber \]

Solve the equation with the calculator. Approximate the solution to the nearest thousandth.

- \(2\sin(x)=4\cos(x)+3\)

- \(5\cos(2x)=\tan(x)\)

Solution

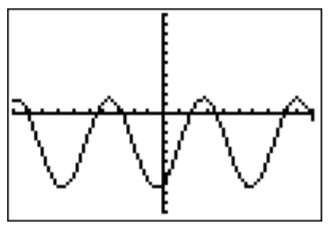

- We rewrite the equation as \(2\sin(x)-4\cos(x)-3=0\), and use the calculator to find the graph of the function \(f(x)=2\sin(x)-4\cos(x)-3\). The zeros of the function \(f\) are the solutions of the initial equation. The graph that we obtain is displayed below.

The graph indicates that the function \(f(x)=2\sin(x)-4\cos(x)-3\) is periodic. This can be confirmed by observing that both \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\) are periodic with period \(2\pi\), and thus also \(f(x)\).

\[f(x+2\pi)= 2\sin(x+2\pi)-4\cos(x+2\pi)-3=2\sin(x)-4\cos(x)-3=f(x) \nonumber \]

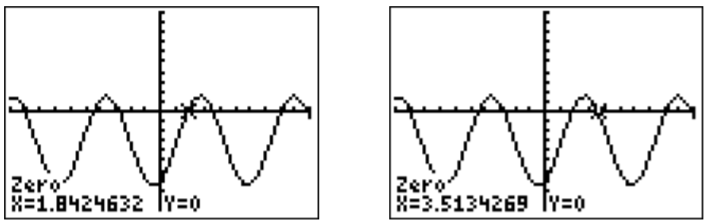

The solution of \(f(x)=0\) can be obtained by finding the “zeros,” that is by pressing \(\boxed{\text{2nd}} \boxed{\text{trace}} \boxed{\text{2}}\), then choosing a left- and right-bound, and making a guess for the zero. Repeating this procedure gives the following two approximate solutions within one period.

The general solution is thus

\[x\approx1.842+2n\pi \quad \text{ or } \quad x\approx3.513+2n\pi, \quad \text{ where } n=0,\pm1,\pm2,\dots \nonumber \]

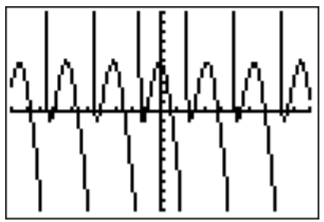

- We rewrite the equation as \(5\cos(2x)-\tan(x)=0\) and graph the function \(f(x)=5\cos(2x)-\tan(x)\) in the standard window.

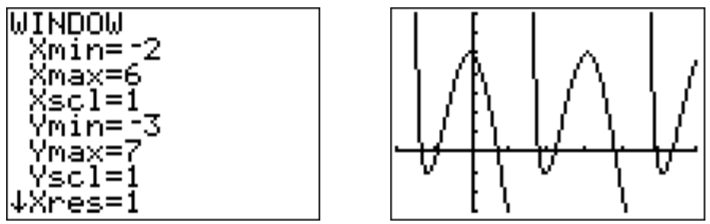

To get a better view of the function we zoom to a more appropriate window.

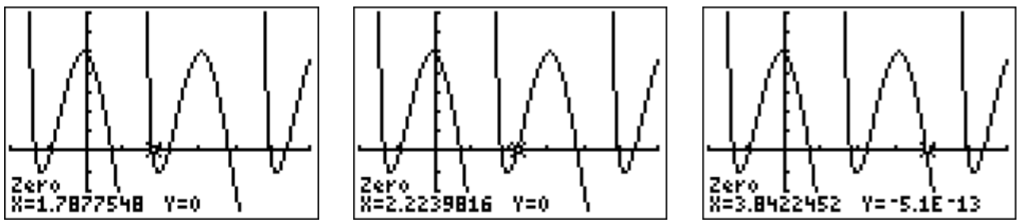

Note again that the function \(f\) is periodic. The period of \(\cos(2x)\) is \(\dfrac{2\pi}{2}=\pi\) (see definition [DEF:amplitude-period-phase] on page ), and the period of \(\tan(x)\) is also \(\pi\) (see equation [EQU:tan-period] on page ). Thus, \(f\) is also periodic with period \(\pi\). The solutions in one period are approximated by finding the zeros with the calculator.

The general solution is given by any of these numbers, with possibly an additional shift by any multiple of \(\pi\).

\[\begin{aligned}

x \approx 1.788+n \pi \quad \text { or } \quad x \approx 2.224+n \pi \quad \text { or } \quad x \approx 3.842+n \pi \quad \text { where } n=0, \pm 1, \pm 2, \pm 3, \ldots \end{aligned} \nonumber \]