5.1: Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

- Learn the definition of eigenvector and eigenvalue.

- Learn to find eigenvectors and eigenvalues geometrically.

- Learn to decide if a number is an eigenvalue of a matrix, and if so, how to find an associated eigenvector.

- Recipe: find a basis for the λ-eigenspace.

- Pictures: whether or not a vector is an eigenvector, eigenvectors of standard matrix transformations.

- Theorem: the expanded invertible matrix theorem.

- Vocabulary word: eigenspace.

- Essential vocabulary words: eigenvector, eigenvalue.

In this section, we define eigenvalues and eigenvectors. These form the most important facet of the structure theory of square matrices. As such, eigenvalues and eigenvectors tend to play a key role in the real-life applications of linear algebra.

Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

Here is the most important definition in this text.

Let A be an n×n matrix.

- An eigenvector of A is a nonzero vector v in Rn such that Av=λv, for some scalar λ.

- An eigenvalue of A is a scalar λ such that the equation Av=λv has a nontrivial solution.

If Av=λv for v≠0, we say that λ is the eigenvalue for v, and that v is an eigenvector for λ.

The German prefix “eigen” roughly translates to “self” or “own”. An eigenvector of A is a vector that is taken to a multiple of itself by the matrix transformation T(x)=Ax, which perhaps explains the terminology. On the other hand, “eigen” is often translated as “characteristic”; we may think of an eigenvector as describing an intrinsic, or characteristic, property of A.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors are only for square matrices.

Eigenvectors are by definition nonzero. Eigenvalues may be equal to zero.

We do not consider the zero vector to be an eigenvector: since A0=0=λ0 for every scalar λ, the associated eigenvalue would be undefined.

If someone hands you a matrix A and a vector v, it is easy to check if v is an eigenvector of A: simply multiply v by A and see if Av is a scalar multiple of v. On the other hand, given just the matrix A, it is not obvious at all how to find the eigenvectors. We will learn how to do this in Section 5.2.

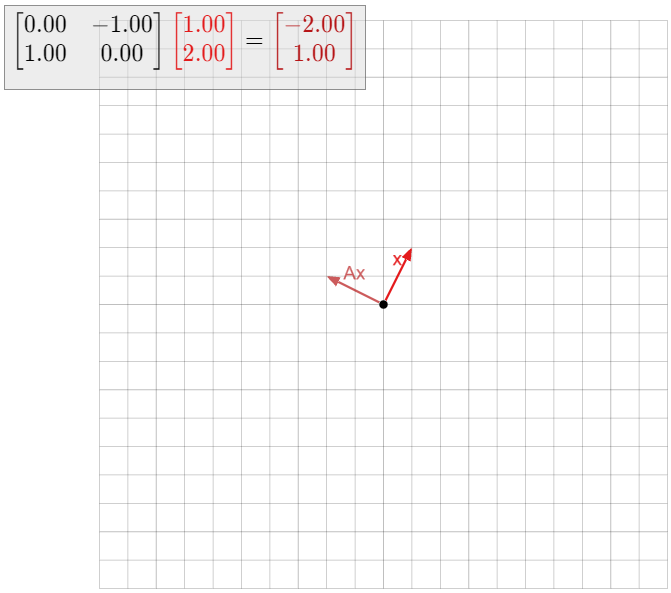

Consider the matrix

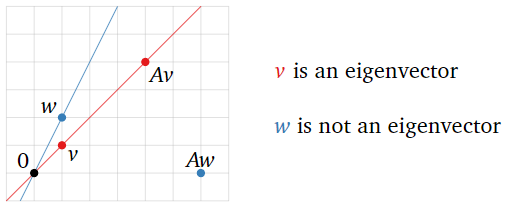

A=(22−48)and vectorsv=(11)w=(21).

Which are eigenvectors? What are their eigenvalues?

Solution

We have

Av=(22−48)(11)=(44)=4v.

Hence, v is an eigenvector of A, with eigenvalue λ=4. On the other hand,

Aw=(22−48)(21)=(60).

which is not a scalar multiple of w. Hence, w is not an eigenvector of A.

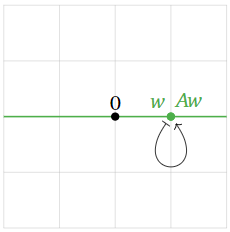

Figure 5.1.1

Consider the matrix

A=(06812000120)and vectorsv=(1641)w=(222).

Which are eigenvectors? What are their eigenvalues?

Solution

We have

Av=(06812000120)(1641)=(3282)=2v.

Hence, v is an eigenvector of A, with eigenvalue λ=2. On the other hand,

Aw=(06812000120)(222)=(2811),

which is not a scalar multiple of w. Hence, w is not an eigenvector of A.

Let

A=(1326)v=(−31).

Is v an eigenvector of A? If so, what is its eigenvalue?

Solution

The product is

Av=(1326)(−31)=(00)=0v.

Hence, v is an eigenvector with eigenvalue zero.

As noted above, an eigenvalue is allowed to be zero, but an eigenvector is not.

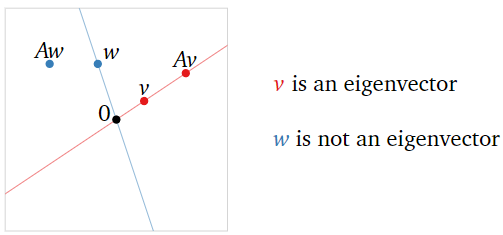

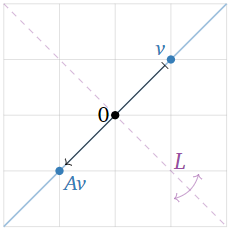

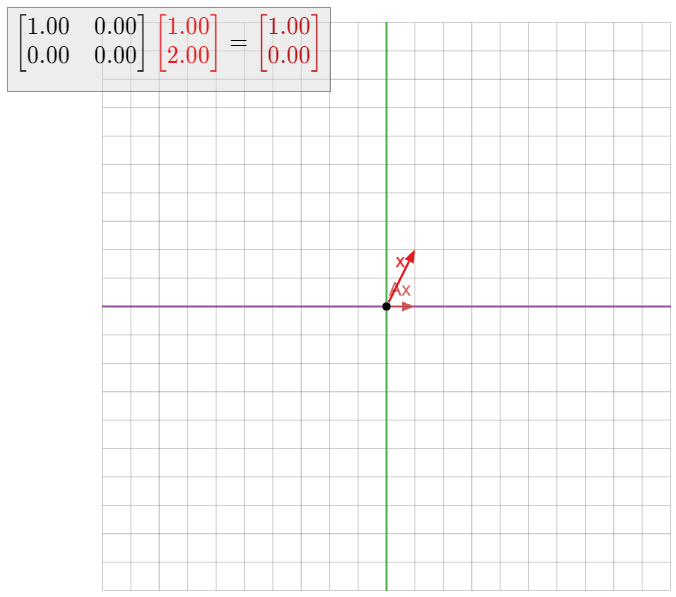

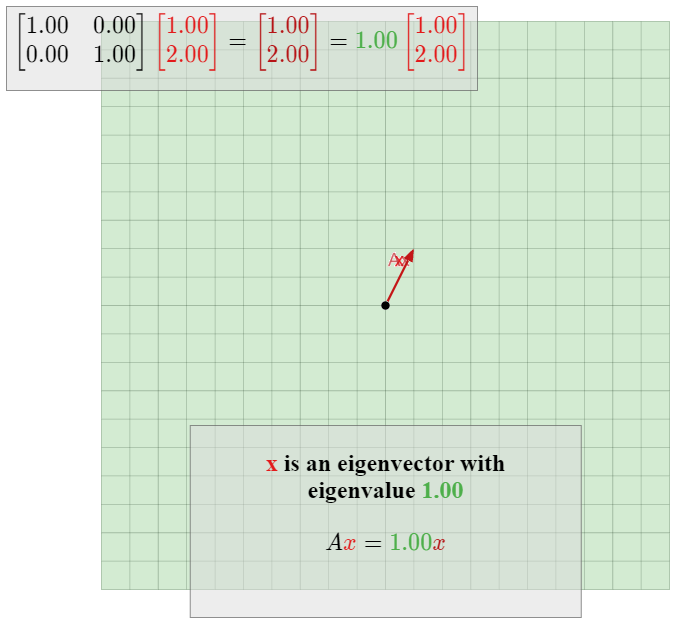

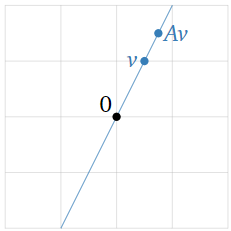

To say that Av=λv means that Av and λv are collinear with the origin. So, an eigenvector of A is a nonzero vector v such that Av and v lie on the same line through the origin. In this case, Av is a scalar multiple of v; the eigenvalue is the scaling factor.

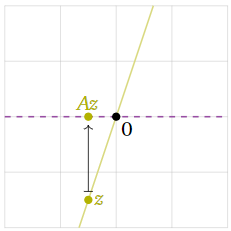

Figure 5.1.2

For matrices that arise as the standard matrix of a linear transformation, it is often best to draw a picture, then find the eigenvectors and eigenvalues geometrically by studying which vectors are not moved off of their line. For a transformation that is defined geometrically, it is not necessary even to compute its matrix to find the eigenvectors and eigenvalues.

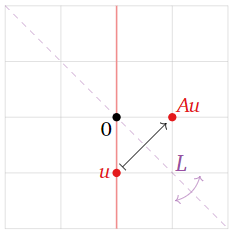

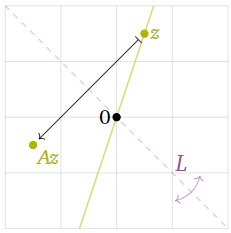

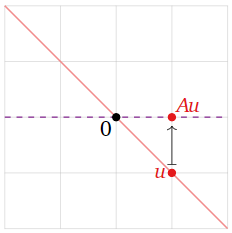

Here is an example of this. Let T:R2→R2 be the linear transformation that reflects over the line L defined by y=−x, and let A be the matrix for T. We will find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of A without doing any computations.

This transformation is defined geometrically, so we draw a picture.

Figure 5.1.3

The vector u is not an eigenvector, because Au is not collinear with u and the origin.

Figure 5.1.4

The vector z is not an eigenvector either.

Figure 5.1.5

The vector v is an eigenvector because Av is collinear with v and the origin. The vector Av has the same length as v, but the opposite direction, so the associated eigenvalue is −1.

Figure 5.1.6

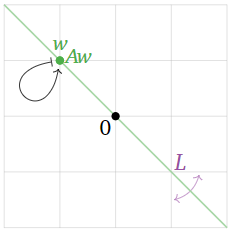

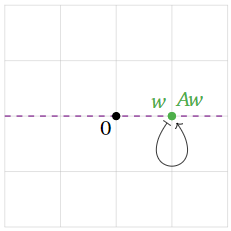

The vector w is an eigenvector because Aw is collinear with w and the origin: indeed, Aw is equal to w! This means that w is an eigenvector with eigenvalue 1.

It appears that all eigenvectors lie either on L, or on the line perpendicular to L. The vectors on L have eigenvalue 1, and the vectors perpendicular to L have eigenvalue −1.

We will now give five more examples of this nature

Let T:R2→R2 be the linear transformation that projects a vector vertically onto the x-axis, and let A be the matrix for T. Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of A without doing any computations.

Solution

This transformation is defined geometrically, so we draw a picture.

Figure 5.1.8

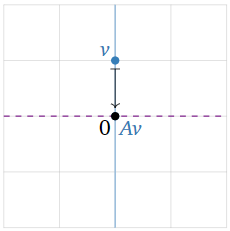

The vector u is not an eigenvector, because Au is not collinear with u and the origin.

Figure 5.1.9

The vector z is not an eigenvector either.

Figure 5.1.10

The vector v is an eigenvector. Indeed, Av is the zero vector, which is collinear with v and the origin; since Av=0v, the associated eigenvalue is 0.

Figure 5.1.11

The vector w is an eigenvector because Aw is collinear with w and the origin: indeed, Aw is equal to w! This means that w is an eigenvector with eigenvalue 1.

It appears that all eigenvectors lie on the x-axis or the y-axis. The vectors on the x-axis have eigenvalue 1, and the vectors on the y-axis have eigenvalue 0.

Find all eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the identity matrix In.

Solution

The identity matrix has the property that Inv=v for all vectors v in Rn. We can write this as Inv=1⋅v, so every nonzero vector is an eigenvector with eigenvalue 1.

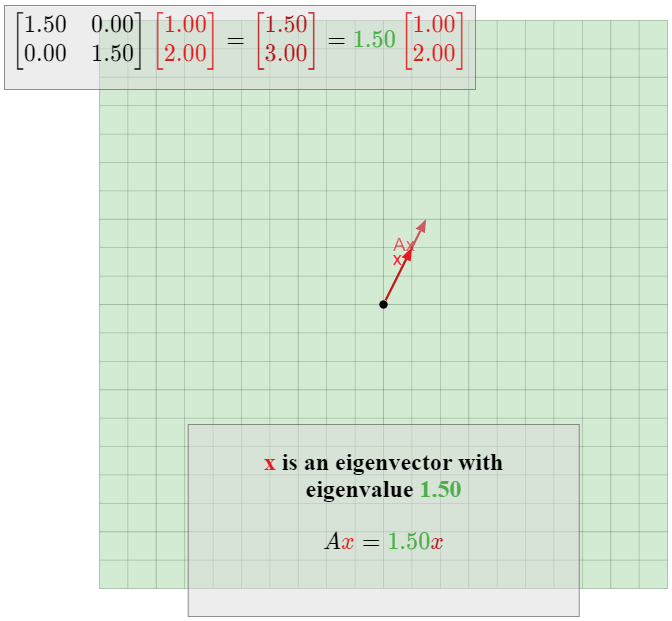

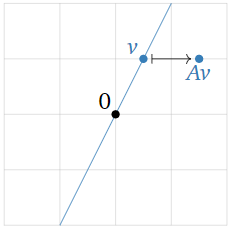

Let T:R2→R2 be the linear transformation that dilates by a factor of 1.5, and let A be the matrix for T. Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of A without doing any computations.

Solution

We have

Av=T(v)=1.5v

for every vector v in R2. Therefore, by definition every nonzero vector is an eigenvector with eigenvalue 1.5.

Figure 5.1.14

Let

A=(1101)

and let T(x)=Ax, so T is a shear in the x-direction. Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of A without doing any computations.

Solution

In equations, we have

A(xy)=(1101)(xy)=(x+yy).

This tells us that a shear takes a vector and adds its y-coordinate to its x-coordinate. Since the x-coordinate changes but not the y-coordinate, this tells us that any vector v with nonzero y-coordinate cannot be collinear with Av and the origin.

Figure 5.1.16

On the other hand, any vector v on the x-axis has zero y-coordinate, so it is not moved by A. Hence v is an eigenvector with eigenvalue 1.

Figure 5.1.17

Accordingly, all eigenvectors of A lie on the x-axis, and have eigenvalue 1.

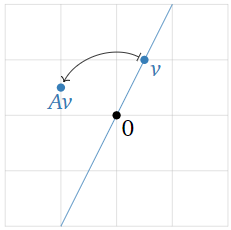

Let T:R2→R2 be the linear transformation that rotates counterclockwise by 90∘, and let A be the matrix for T. Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of A without doing any computations.

Solution

If v is any nonzero vector, then Av is rotated by an angle of 90∘ from v. Therefore, Av is not on the same line as v, so v is not an eigenvector. And of course, the zero vector is never an eigenvector.

Figure 5.1.19

Therefore, this matrix has no eigenvectors and eigenvalues.

Here we mention one basic fact about eigenvectors.

Let v1,v2,…,vk be eigenvectors of a matrix A, and suppose that the corresponding eigenvalues λ1,λ2,…,λk are distinct (all different from each other). Then {v1,v2,…,vk} is linearly independent.

- Proof

-

Suppose that {v1,v2,…,vk} were linearly dependent. According to the increasing span criterion, Theorem 2.5.2 in Section 2.5, this means that for some j, the vector vj is in Span{v1,v2,…,vj−1}. If we choose the first such j, then {v1,v2,…,vj−1} is linearly independent. Note that j>1 since v1≠0.

Since vj is in Span{v1,v2,…,vj−1},, we can write

vj=c1v1+c2v2+⋯+cj−1vj−1

for some scalars c1,c2,…,cj−1. Multiplying both sides of the above equation by A gives

λjvj=Avj=A(c1v1+c2v2+⋯+cj−1vj−1)=c1Av1+c2Av2+⋯+cj−1Avj−1=c1λ1v1+c2λ2v2+⋯+cj−1λj−1vj−1.

Subtracting λj times the first equation from the second gives

0=λjvj−λjvj=c1(λ1−λj)v1+c2(λ2−λj)v2+⋯+cj−1(λj−1−λj)vj−1.

Since λi≠λj for i<j, this is an equation of linear dependence among v1,v2,…,vj−1, which is impossible because those vectors are linearly independent. Therefore, {v1,v2,…,vk} must have been linearly independent after all.

When k=2, this says that if v1,v2 are eigenvectors with eigenvalues λ1≠λ2, then v2 is not a multiple of v1. In fact, any nonzero multiple cv1 of v1 is also an eigenvector with eigenvalue λ1:

A(cv1)=cAv1=c(λ1v1)=λ1(cv1).

As a consequence of the above Fact 5.1.1, we have the following.

An n×n matrix A has at most n eigenvalues.

Eigenspaces

Suppose that A is a square matrix. We already know how to check if a given vector is an eigenvector of A and in that case to find the eigenvalue. Our next goal is to check if a given real number is an eigenvalue of A and in that case to find all of the corresponding eigenvectors. Again this will be straightforward, but more involved. The only missing piece, then, will be to find the eigenvalues of A; this is the main content of Section 5.2.

Let A be an n×n matrix, and let λ be a scalar. The eigenvectors with eigenvalue λ, if any, are the nonzero solutions of the equation Av=λv. We can rewrite this equation as follows:

Av=λv⟺Av−λv=0⟺Av−λInv=0⟺(A−λIn)v=0.

Therefore, the eigenvectors of A with eigenvalue λ, if any, are the nontrivial solutions of the matrix equation (A−λIn)v=0, i.e., the nonzero vectors in Nul(A−λIn). If this equation has no nontrivial solutions, then λ is not an eigenvector of A.

The above observation is important because it says that finding the eigenvectors for a given eigenvalue means solving a homogeneous system of equations. For instance, if

A=(713−32−3−3−2−1),

then an eigenvector with eigenvalue λ is a nontrivial solution of the matrix equation

(713−32−3−3−2−1)(xyz)=λ(xyz).

This translates to the system of equations

{7x+y+3z=λx−3x+2y−3z=λy−3x−2y−z=λz⟶{(7−λ)x+y+3z=0−3x+(2−λ)y−3z=0−3x−2y+(−1−λ)z=0.

This is the same as the homogeneous matrix equation

(7−λ13−32−λ−3−3−2−1−λ)(xyz)=0,

i.e., (A−λI3)v=0.

Let A be an n×n matrix, and let λ be an eigenvalue of A. The λ-eigenspace of A is the solution set of (A−λIn)v=0, i.e., the subspace Nul(A−λIn).

The λ-eigenspace is a subspace because it is the null space of a matrix, namely, the matrix A−λIn. This subspace consists of the zero vector and all eigenvectors of A with eigenvalue λ.

Since a nonzero subspace is infinite, every eigenvalue has infinitely many eigenvectors. (For example, multiplying an eigenvector by a nonzero scalar gives another eigenvector.) On the other hand, there can be at most n linearly independent eigenvectors of an n×n matrix, since Rn has dimension n.

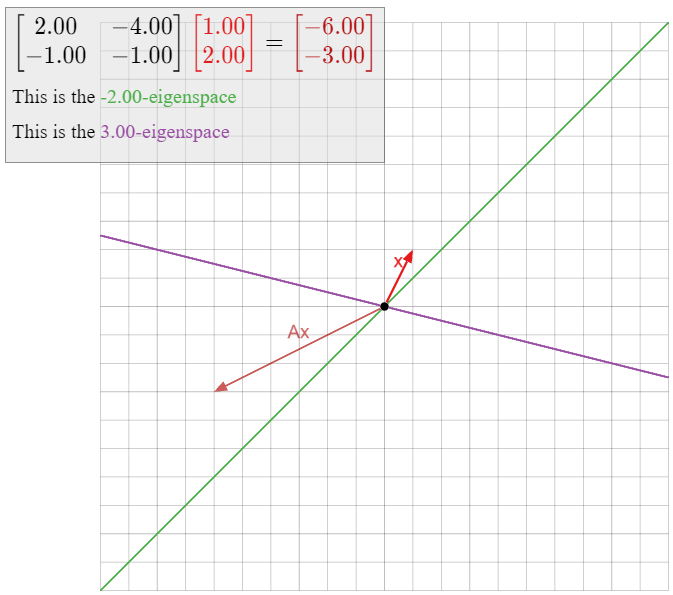

For each of the numbers λ=−2,1,3, decide if λ is an eigenvalue of the matrix

A=(2−4−1−1),

and if so, compute a basis for the λ-eigenspace.

Solution

The number 3 is an eigenvalue of A if and only if Nul(A−3I2) is nonzero. Hence, we have to solve the matrix equation (A−3I2)v=0. We have

A−3I2=(2−4−1−1)−3(1001)=(−1−4−1−4).

The reduced row echelon form of this matrix is

(1400)parametricform→{x=−4yy=yparametricvector form→(xy)=y(−41).

Since y is a free variable, the null space of A−3I2 is nonzero, so 3 is an eigenvector. A basis for the 3-eigenspace is {(−41)}.

Concretely, we have shown that the eigenvectors of A with eigenvalue 3 are exactly the nonzero multiples of (−41). In particular, (−41) is an eigenvector, which we can verify:

(2−4−11)(−41)=(−123)=3(−41).

The number 1 is an eigenvalue of A if and only if Nul(A−I2) is nonzero. Hence, we have to solve the matrix equation (A−I2)v=0. We have

A−I2=(2−4−1−1)−(1001)=(1−4−1−2).

This matrix has determinant −6, so it is invertible. By Theorem 3.6.1 in Section 3.6, we have Nul(A−I2)={0}, so 1 is not an eigenvalue.

The eigenvectors of A with eigenvalue −2, if any, are the nonzero solutions of the matrix equation (A+2I2)v=0. We have

A+2I2=(2−4−1−1)+2(1001)=(4−4−11).

The reduced row echelon form of this matrix is

(1−100)parametricform→{x=yy=yparametricvector form→(xy)=y(11).

Hence there exist eigenvectors with eigenvalue −2, namely, any nonzero multiple of (11). A basis for the −2-eigenspace is {(11)}.

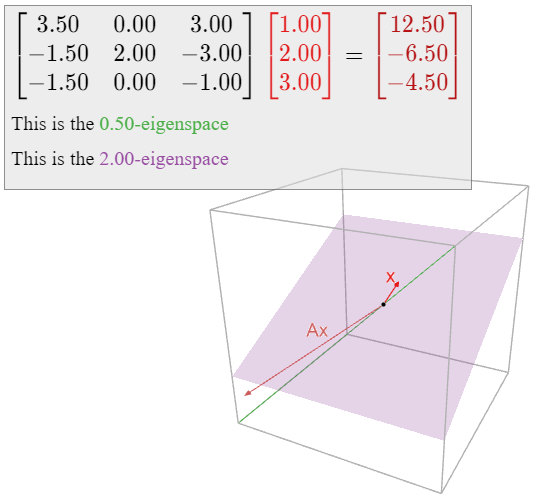

For each of the numbers λ=0,12,2, decide if λ is an eigenvector of the matrix

A=(7/203−3/22−3−3/20−1),

and if so, compute a basis for the λ-eigenspace.

Solution

The number 2 is an eigenvalue of A if and only if Nul(A−2I3) is nonzero. Hence, we have to solve the matrix equation (A−2I3)v=0. We have

A−2I3=(7/203−3/22−3−3/201)−2(100010001)=(3/203−3/20−3−3/20−3).

The reduced row echelon form of this matrix is

(102000000)parametricform→{x=−2zy=yz=zparametricvector form→(xyz)=y(010)+z(−201).

The matrix A−2I3 has two free variables, so the null space of A−2I3 is nonzero, and thus 2 is an eigenvector. A basis for the 2-eigenspace is

{(010),(−201)}.

This is a plane in R3.

The eigenvectors of A with eigenvalue 12, if any, are the nonzero solutions of the matrix equation (A−12I3)v=0. We have

A−12I3=(7/203−3/22−3−3/201)−12(100010001)=(303−3/23/2−3−3/20−3/2).

The reduced row echelon form of this matrix is

(10101−1000)parametricform→{x=−zy=zz=zparametricvector form→(xyz)=z(−111).

Hence there exist eigenvectors with eigenvalue 12, so 12 is an eigenvalue. A basis for the 12-eigenspace is

{(−111)}.

This is a line in R3.

The number 0 is an eigenvalue of A if and only if Nul(A−0I3)=Nul(A) is nonzero. This is the same as asking whether A is noninvertible, by Theorem 3.6.1 in Section 3.6. The determinant of A is det so A is invertible by the invertibility property, Proposition 4.1.2 in Section 4.1. It follows that 0 is not an eigenvalue of A.

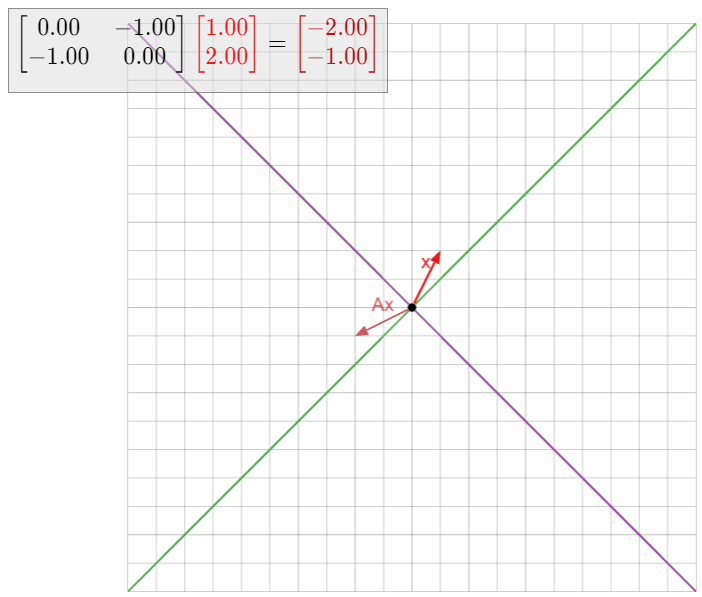

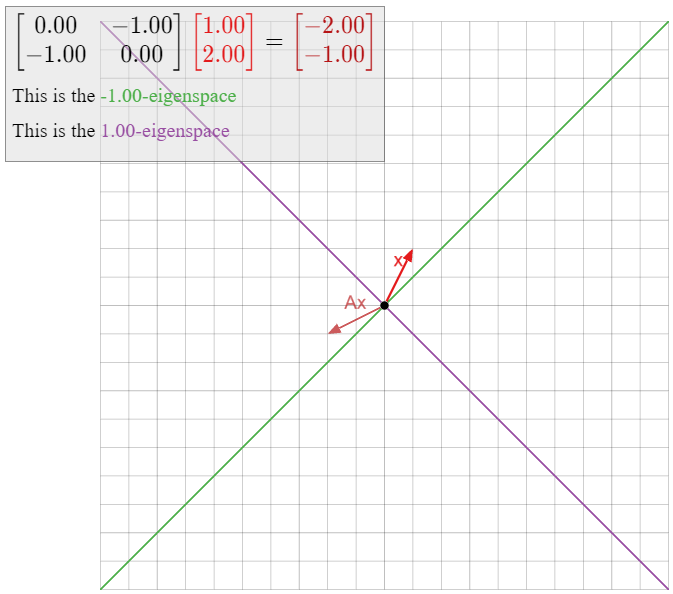

Let T\colon\mathbb{R}^2\to\mathbb{R}^2 be the linear transformation that reflects over the line L defined by y=-x\text{,} and let A be the matrix for T. Find all eigenspaces of A.

Solution

We showed in Example \PageIndex{4} that all eigenvectors with eigenvalue 1 lie on L\text{,} and all eigenvectors with eigenvalue -1 lie on the line L^\perp that is perpendicular to L. Hence, L is the 1-eigenspace, and L^\perp is the -1-eigenspace.

None of this required any computations, but we can verify our conclusions using algebra. First we compute the matrix A\text{:}

T\left(\begin{array}{c}1\\0\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{c}0\\-1\end{array}\right)\quad T\left(\begin{array}{c}0\\1\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{c}-1\\0\end{array}\right)\quad\implies\quad A=\left(\begin{array}{cc}0&-1\\-1&0\end{array}\right).\nonumber

Computing the 1-eigenspace means solving the matrix equation (A-I_2)v=0. We have

A-I_{2}=\left(\begin{array}{cc}0&-1\\-1&0\end{array}\right)-\left(\begin{array}{cc}1&0\\0&1\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{cc}-1&-1\\-1&-1\end{array}\right)\quad\xrightarrow{\text{RREF}}\quad\left(\begin{array}{cc}1&1\\0&0\end{array}\right).\nonumber

The parametric form of the solution set is x = -y\text{,} or equivalently, y = -x\text{,} which is exactly the equation for L. Computing the -1-eigenspace means solving the matrix equation (A+I_2)v=0\text{;} we have

A+I_{2}=\left(\begin{array}{cc}0&-1\\-1&0\end{array}\right)+\left(\begin{array}{cc}1&0\\0&1\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{cc}1&-1\\-1&1\end{array}\right)\quad\xrightarrow{\text{RREF}}\quad\left(\begin{array}{cc}1&-1\\0&0\end{array}\right).\nonumber

The parametric form of the solution set is x = y\text{,} or equivalently, y = x\text{,} which is exactly the equation for L^\perp.

Let A be an n\times n matrix and let \lambda be a number.

- \lambda is an eigenvalue of A if and only if (A-\lambda I_n)v = 0 has a nontrivial solution, if and only if \text{Nul}(A-\lambda I_n)\neq\{0\}.

- In this case, finding a basis for the \lambda-eigenspace of A means finding a basis for \text{Nul}(A-\lambda I_n)\text{,} which can be done by finding the parametric vector form of the solutions of the homogeneous system of equations (A-\lambda I_n)v = 0.

- The dimension of the \lambda-eigenspace of A is equal to the number of free variables in the system of equations (A-\lambda I_n)v = 0\text{,} which is the number of columns of A - \lambda I_n without pivots.

- The eigenvectors with eigenvalue \lambda are the nonzero vectors in \text{Nul}(A-\lambda I_n), or equivalently, the nontrivial solutions of (A-\lambda I_n)v = 0.

We conclude with an observation about the 0-eigenspace of a matrix.

Let A be an n\times n matrix.

- The number 0 is an eigenvalue of A if and only if A is not invertible.

- In this case, the 0-eigenspace of A is \text{Nul}(A).

- Proof

-

We know that 0 is an eigenvalue of A if and only if \text{Nul}(A - 0I_n) = \text{Nul}(A) is nonzero, which is equivalent to the noninvertibility of A by Theorem 3.6.1 in Section 3.6. In this case, the 0-eigenspace is by definition \text{Nul}(A-0I_n) = \text{Nul}(A).

Concretely, an eigenvector with eigenvalue 0 is a nonzero vector v such that Av=0v\text{,} i.e., such that Av = 0. These are exactly the nonzero vectors in the null space of A.

The Invertible Matrix Theorem: Addenda

We now have two new ways of saying that a matrix is invertible, so we add them to the invertible matrix theorem, Theorem 3.6.1 in Section 3.6.

Let A be an n\times n matrix, and let T\colon\mathbb{R}^n \to\mathbb{R}^n be the matrix transformation T(x) = Ax. The following statements are equivalent:

- A is invertible.

- A has n pivots.

- \text{Nul}(A) = \{0\}.

- The columns of A are linearly independent.

- The columns of A span \mathbb{R}^n .

- Ax=b has a unique solution for each b in \mathbb{R}^n .

- T is invertible.

- T is one-to-one.

- T is onto.

- \det(A) \neq 0.

- 0 is not an eigenvalue of A.