6.1: Complex Numbers

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

- Understand the geometric significance of a complex number as a point in the plane.

- Prove algebraic properties of addition and multiplication of complex numbers, and apply these properties. Understand the action of taking the conjugate of a complex number.

- Understand the absolute value of a complex number and how to find it as well as its geometric significance.

Although very powerful, the real numbers are inadequate to solve equations such as x2+1=0, and this is where complex numbers come in. We define the number i as the imaginary number such that i2=−1, and define complex numbers as those of the form z=a+bi where a and b are real numbers. We call this the standard form, or Cartesian form, of the complex number z. Then, we refer to a as the real part of z, and b as the imaginary part of z. It turns out that such numbers not only solve the above equation, but in fact also solve any polynomial of degree at least 1 with complex coefficients. This property, called the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra, is sometimes referred to by saying C is algebraically closed. Gauss is usually credited with giving a proof of this theorem in 1797 but many others worked on it and the first completely correct proof was due to Argand in 1806.

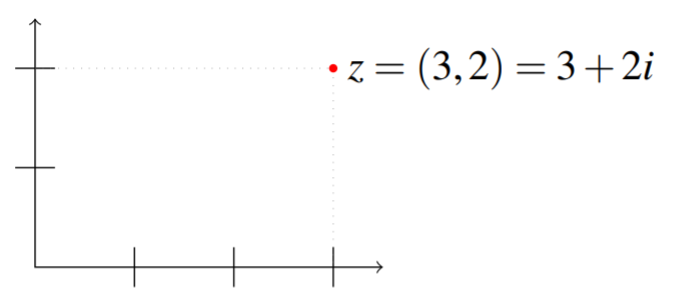

Just as a real number can be considered as a point on the line, a complex number z=a+bi can be considered as a point (a,b) in the plane whose x coordinate is a and whose y coordinate is b. For example, in the following picture, the point z=3+2i can be represented as the point in the plane with coordinates (3,2).

Addition of complex numbers is defined as follows. (a+bi)+(c+di)=(a+c)+(b+d)i

This addition obeys all the usual properties as the following theorem indicates.

Let z,w, and v be complex numbers. Then the following properties hold.

- Commutative Law for Addition z+w=w+z

- Additive Identity z+0=z

- Existence of Additive Inverse For eachz∈C,there exists−z∈C such thatz+(−z)=0In fact if z=a+bi, then −z=−a−bi.

- Associative Law for Addition (z+w)+v=z+(w+v)

- Proof

-

The proof of this theorem is left as an exercise for the reader.

Now, multiplication of complex numbers is defined the way you would expect, recalling that i2=−1. (a+bi)(c+di)=ac+adi+bci+i2bd=(ac−bd)+(ad+bc)i

Consider the following examples.

- (2−3i)(−3+4i)=6+17i

- (4−7i)(6−2i)=10−50i

- (−3+6i)(5−i)=−9+33i

The following are important properties of multiplication of complex numbers.

Let z,w and v be complex numbers. Then, the following properties of multiplication hold.

- Commutative Law for Multiplication zw=wz

- Associative Law for Multiplication (zw)v=z(wv)

- Multiplicative Identity 1z=z

- Existence of Multiplicative Inverse For eachz≠0,there existsz−1 such thatzz−1=1

- Distributive Law z(w+v)=zw+zv

You may wish to verify some of these statements. The real numbers also satisfy the above axioms, and in general any mathematical structure which satisfies these axioms is called a field. There are many other fields, in particular even finite ones particularly useful for cryptography, and the reason for specifying these axioms is that linear algebra is all about fields and we can do just about anything in this subject using any field. Although here, the fields of most interest will be the familiar field of real numbers, denoted as R, and the field of complex numbers, denoted as C.

An important construction regarding complex numbers is the complex conjugate denoted by a horizontal line above the number, ¯z. It is defined as follows.

Let z=a+bi be a complex number. Then the conjugate of z, written ¯z is given by ¯a+bi=a−bi

Geometrically, the action of the conjugate is to reflect a given complex number across the x axis. Algebraically, it changes the sign on the imaginary part of the complex number. Therefore, for a real number a, ¯a=a.

- If z=3+4i, then ¯z=3−4i, i.e., ¯3+4i=3−4i.

- ¯−2+5i=−2−5i.

- ¯i=−i.

- ¯7=7.

Consider the following computation.

(¯a+bi)(a+bi)=(a−bi)(a+bi)=a2+b2−(ab−ab)i=a2+b2

Notice that there is no imaginary part in the product, thus multiplying a complex number by its conjugate results in a real number.

Let z and w be complex numbers. Then, the following properties of the conjugate hold.

- ¯z±w=¯z±¯w.

- ¯(zw)=¯z ¯w.

- ¯(¯z)=z.

- ¯(zw)=¯z¯w.

- z is real if and only if ¯z=z.

Division of complex numbers is defined as follows. Let z=a+bi and w=c+di be complex numbers such that c,d are not both zero. Then the quotient z divided by w is

zw=a+bic+di=a+bic+di×c−dic−di=(ac+bd)+(bc−ad)ic2+d2=ac+bdc2+d2+bc−adc2+d2i.

In other words, the quotient zw is obtained by multiplying both top and bottom of zw by ¯w and then simplifying the expression.

1i=1i×−i−i=−i−i2=−i

2−i3+4i=2−i3+4i×3−4i3−4i=(6−4)+(−3−8)i32+42=2−11i25=225−1125i

1−2i−2+5i=1−2i−2+5i×−2−5i−2−5i=(−2−10)+(4−5)i22+52=−1229−129i

Interestingly every nonzero complex number a+bi has a unique multiplicative inverse. In other words, for a nonzero complex number z, there exists a number z−1 (or 1z) so that zz−1=1. Note that z=a+bi is nonzero exactly when a2+b2≠0, and its inverse can be written in standard form as defined now.

Let z=a+bi be a complex number. Then the multiplicative inverse of z, written z−1 exists if and only if a2+b2≠0 and is given by

z−1=1a+bi=1a+bi×a−bia−bi=a−bia2+b2=aa2+b2−iba2+b2

Note that we may write z−1 as 1z. Both notations represent the multiplicative inverse of the complex number z. Consider now an example.

Consider the complex number z=2+6i. Then z−1 is defined, and

1z=12+6i=12+6i×2−6i2−6i=2−6i22+62=2−6i40=120−320i

You can always check your answer by computing zz−1.

Another important construction of complex numbers is that of the absolute value, also called the modulus. Consider the following definition.

The absolute value, or modulus, of a complex number, denoted |z| is defined as follows. |a+bi|=√a2+b2

Thus, if z is the complex number z=a+bi, it follows that |z|=(z¯z)1/2

Also from the definition, if z=a+bi and w=c+di are two complex numbers, then |zw|=|z||w|. Take a moment to verify this.

The triangle inequality is an important property of the absolute value of complex numbers. There are two useful versions which we present here, although the first one is officially called the triangle inequality.

Let z,w be complex numbers.

The following two inequalities hold for any complex numbers z,w: |z+w|≤|z|+|w|||z|−|w||≤|z−w| The first one is called the Triangle Inequality.

- Proof

-

Let z=a+bi and w=c+di. First note that z¯w=(a+bi)(c−di)=ac+bd+(bc−ad)i and so |ac+bd|≤|z¯w|=|z||w|.

Then, |z+w|2=(a+c+i(b+d))(a+c−i(b+d)) =(a+c)2+(b+d)2=a2+c2+2ac+2bd+b2+d2 ≤|z|2+|w|2+2|z||w|=(|z|+|w|)2

Taking the square root, we have that |z+w|≤|z|+|w| so this verifies the triangle inequality.

To get the second inequality, write z=z−w+w,w=w−z+z and so by the first form of the inequality we get both: |z|≤|z−w|+|w|,|w|≤|z−w|+|z|

Hence, both |z|−|w| and |w|−|z| are no larger than |z−w|. This proves the second version because ||z|−|w|| is one of |z|−|w| or |w|−|z|.

With this definition, it is important to note the following. You may wish to take the time to verify this remark.

Let z=a+bi and w=c+di. Then

|z−w|=√(a−c)2+(b−d)2.

Thus the distance between the point in the plane determined by the ordered pair (a,b) and the ordered pair (c,d) equals |z−w| where z and w are as just described.

For example, consider the distance between (2,5) and (1,8). Letting z=2+5i and w=1+8i, z−w=1−3i, (z−w)(¯z−w)=(1−3i)(1+3i)=10 so |z−w|=√10.

Recall that we refer to z=a+bi as the standard form of the complex number. In the next section, we examine another form in which we can express the complex number.