2.6: Subspaces

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

- Learn the definition of a subspace.

- Learn to determine whether or not a subset is a subspace.

- Learn the most important examples of subspaces.

- Learn to write a given subspace as a column space or null space.

- Recipe: compute a spanning set for a null space.

- Picture: whether a subset of R2 or R3 is a subspace or not.

- Vocabulary words: subspace, column space, null space.

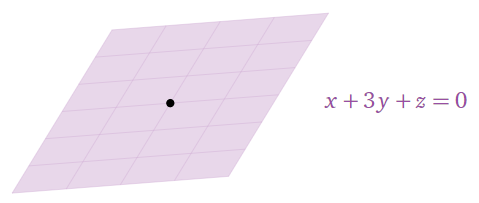

In this section we discuss subspaces of Rn. A subspace turns out to be exactly the same thing as a span, except we don’t have a particular set of spanning vectors in mind. This change in perspective is quite useful, as it is easy to produce subspaces that are not obviously spans. For example, the solution set of the equation x+3y+z=0 is a span because the equation is homogeneous, but we would have to compute the parametric vector form in order to write it as a span.

Figure 2.6.1

(A subspace also turns out to be the same thing as the solution set of a homogeneous system of equations.)

Subspaces: Definition and Examples

A subset of Rn is any collection of points of Rn.

For instance, the unit circle

C={(x,y) in R2|x2+y2=1}

is a subset of R2.

Above we expressed C in set builder notation, Note 2.2.3 in Section 2.2: in English, it reads “C is the set of all ordered pairs (x,y) in R2 such that x2+y2=1.”

A subspace of Rn is a subset V of Rn satisfying:

- Non-emptiness: The zero vector is in V.

- Closure under addition: If u and v are in V, then u+v is also in V.

- Closure under scalar multiplication: If v is in V and c is in R, then cv is also in V.

As a consequence of these properties, we see:

- If v is a vector in V, then all scalar multiples of v are in V by the third property. In other words the line through any nonzero vector in V is also contained in V.

- If u,v are vectors in V and c,d are scalars, then cu,dv are also in V by the third property, so cu+dv is in V by the second property. Therefore, all of Span{u,v} is contained in V

- Similarly, if v1,v2,…,vn are all in V, then Span{v1,v2,…,vn} is contained in V. In other words, a subspace contains the span of any vectors in it.

If you choose enough vectors, then eventually their span will fill up V, so we already see that a subspace is a span. See this Theorem 2.6.1 below for a precise statement.

Suppose that V is a non-empty subset of Rn that satisfies properties 2 and 3. Let v be any vector in V. Then 0v=0 is in V by the third property, so V automatically satisfies property 1. It follows that the only subset of Rn that satisfies properties 2 and 3 but not property 1 is the empty subset {}. This is why we call the first property “non-emptiness”.

The set Rn is a subspace of itself: indeed, it contains zero, and is closed under addition and scalar multiplication.

The set {0} containing only the zero vector is a subspace of Rn: it contains zero, and if you add zero to itself or multiply it by a scalar, you always get zero.

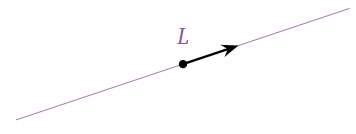

A line L through the origin is a subspace.

Figure 2.6.2

Indeed, L contains zero, and is easily seen to be closed under addition and scalar multiplication.

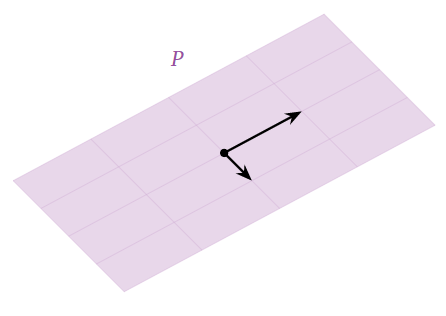

A plane P through the origin is a subspace.

Figure 2.6.3

Indeed, P contains zero; the sum of two vectors in P is also in P; and any scalar multiple of a vector in P is also in P.

A line L (or any other subset) that does not contain the origin is not a subspace. It fails the first defining property: every subspace contains the origin by definition.

Figure 2.6.4

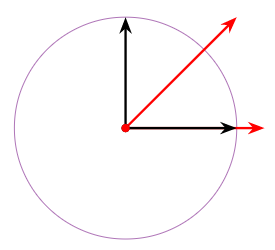

The unit circle C is not a subspace. It fails all three defining properties: it does not contain the origin, it is not closed under addition, and it is not closed under scalar multiplication. In the picture, one red vector is the sum of the two black vectors (which are contained in C), and the other is a scalar multiple of a black vector.

Figure 2.6.5

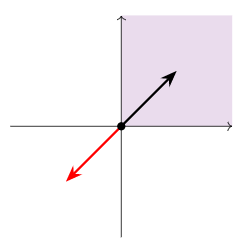

The first quadrant in R2 is not a subspace. It contains the origin and is closed under addition, but it is not closed under scalar multiplication (by negative numbers).

Figure 2.6.6

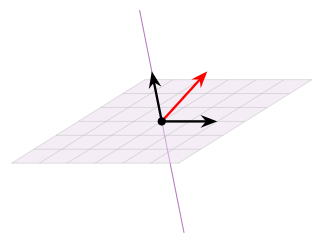

The union of a line and a plane in R3 is not a subspace. It contains the origin and is closed under scalar multiplication, but it is not closed under addition: the sum of a vector on the line and a vector on the plane is not contained in the line or in the plane.

Figure 2.6.7

A subset of Rn is any collection of vectors whatsoever. For instance, the unit circle

C={(x,y) in R2|x2+y2=1}

is a subset of R2, but it is not a subspace. In fact, all of the non-examples above are still subsets of Rn. A subspace is a subset that happens to satisfy the three additional defining properties.

In order to verify that a subset of Rn is in fact a subspace, one has to check the three defining properties. That is, unless the subset has already been verified to be a subspace: see this important note, Note 2.6.3, below.

Let

V={(ab) in R2|2a=3b}.

Verify that V is a subspace.

Solution

First we point out that the condition “2a=3b” defines whether or not a vector is in V: that is, to say (ab) is in V means that 2a=3b. In other words, a vector is in V if twice its first coordinate equals three times its second coordinate. So for instance, (32) and (1/21/3) are in V, but (23) is not because 2⋅2≠3⋅3.

Let us check the first property. The subset V does contain the zero vector (00), because 2⋅0=3⋅0.

Next we check the second property. To show that V is closed under addition, we have to check that for any vectors u=(ab) and v=(cd) in V, the sum u+v is in V. Since we cannot assume anything else about u and v, we must treat them as unknowns.

We have

(ab)+(cd)=(a+cb+d).

To say that (a+cb+d) is contained in V means that 2(a+c)=3(b+d), or 2a+2c=3b+3d. The one thing we are allowed to assume about u and v is that 2a=3b and 2c=3d, so we see that u+v is indeed contained in V.

Next we check the third property. To show that V is closed under scalar multiplication, we have to check that for any vector v=(ab) in V and any scalar c in R, the product cv is in V. Again, we must treat v and c as unknowns. We have

c(ab)=(cacb).

To say that (cacb) is contained in V means that 2(ca)=3(cb), i.e., that c⋅2a=c⋅3b. The one thing we are allowed to assume about v is that 2a=3b, so cv is indeed contained in V.

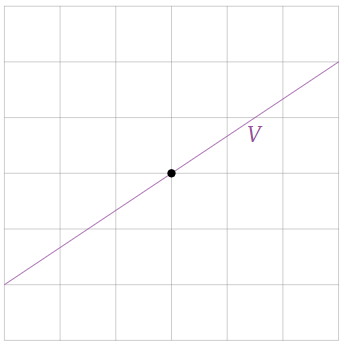

Since V satisfies all three defining properties, it is a subspace. In fact, it is the line through the origin with slope 2/3.

Figure 2.6.8

Let

V={(ab) in R2|ab=0}.

Is V a subspace?

Solution

First we point out that the condition “ab=0” defines whether or not a vector is in V: that is, to say (ab) is in V means that ab=0. In other words, a vector is in V if the product of its coordinates is zero, i.e., if one (or both) of its coordinates are zero. So for instance, (10) and (02) are in V, but (11) is not because 1⋅1≠0.

Let us check the first property. The subset V does contain the zero vector (00), because 0⋅0=0.

Next we check the third property. To show that V is closed under scalar multiplication, we have to check that for any vector v=(ab) in V and any scalar c in R, the product cv is in V. Since we cannot assume anything else about v and c, we must treat them as unknowns.

We have

c(ab)=(cacb).

To say that (cacb) is contained in V means that (ca)(cb)=0. Rewriting, this means c2(ab)=0. The one thing we are allowed to assume about v is that ab=0, so we see that cv is indeed contained in V.

Next we check the second property. It turns out that V is not closed under addition; to verify this, we must show that there exists some vectors u,v in V such that u+v is not contained in V. The easiest way to do so is to produce examples of such vectors. We can take u=(10) and v=(01); these are contained in V because the products of their coordinates are zero, but

(10)+(01)=(11)

is not contained in V because 1⋅1≠0.

Since V does not satisfy the second property (it is not closed under addition), we conclude that V is not a subspace. Indeed, it is the union of the two coordinate axes, which is not a span.

Figure 2.6.9

Common Types of Subspaces

If v1,v2,…,vp are any vectors in Rn, then Span{v1,v2,…,vp} is a subspace of Rn. Moreover, any subspace of Rn can be written as a span of a set of p linearly independent vectors in Rn for p≤n.

- Proof

-

To show that Span{v1,v2,…,vp} is a subspace, we have to verify the three defining properties.

- The zero vector 0=0v1+0v2+⋯+0vp is in the span.

- If u=a1v1+a2v2+⋯+apvp and v=b1v1+b2v2+⋯+bpvp are in Span{v1,v2,…,vp}, then

u+v=(a1+b1)v1+(a2+b2)v2+⋯+(ap+bp)vp

is also in Span{v1,v2,…,vp}. - If v=a1v1+a2v2+⋯+apvp is in Span{v1,v2,…,vp} and c is a scalar, then

cv=ca1v1+ca2v2+⋯+capvp

is also in Span{v1,v2,…,vp}.

Since Span{v1,v2,…,vp} satisfies the three defining properties of a subspace, it is a subspace.

Now let V be a subspace of Rn. If V is the zero subspace, then it is the span of the empty set, so we may assume V is nonzero. Choose a nonzero vector v1 in V. If V=Span{v1}, then we are done. Otherwise, there exists a vector v2 that is in V but not in Span{v1}. Then Span{v1,v2} is contained in V, and by the increasing span criterion in Section 2.5, Theorem 2.5.2, the set {v1,v2} is linearly independent. If V=Span{v1,v2} then we are done. Otherwise, we continue in this fashion until we have written V=Span{v1,v2,…,vp} for some linearly independent set {v1,v2,…,vp}. This process terminates after at most n steps by this important note in Section 2.5, Note 2.5.2.

If V=Span{v1,v2,…,vp}, we say that V is the subspace spanned by or generated by the vectors v1,v2,…,vp. We call {v1,v2,…,vp} a spanning set for V.

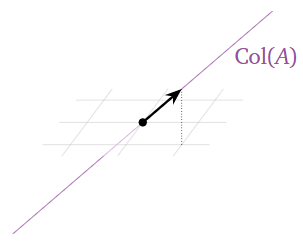

Any matrix naturally gives rise to two subspaces.

Let A be an m×n matrix.

- The column space of A is the subspace of Rm spanned by the columns of A. It is written Col(A).

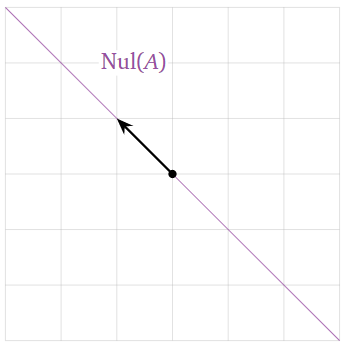

- The null space of A is the subspace of Rn consisting of all solutions of the homogeneous equation Ax=0:

Nul(A)={x in Rn|Ax=0}.

The column space is defined to be a span, so it is a subspace by the above Theorem, Theorem 2.6.1. We need to verify that the null space is really a subspace. In Section 2.4 we already saw that the set of solutions of Ax=0 is always a span, so the fact that the null spaces is a subspace should not come as a surprise.

We have to verify the three defining properties. To say that a vector v is in Nul(A) means that Av=0.

- The zero vector is in Nul(A) because A0=0.

- Suppose that u,v are in Nul(A). This means that Au=0 and Av=0. Hence

A(u+v)=Au+Av=0+0=0

by the linearity of the matrix-vector product in Section 2.3, Proposition 2.3.1. Therefore, u+v is in Nul(A). - Suppose that v is in Nul(A) and c is a scalar. Then

A(cv)=cAv=c⋅0=0 by the linearity of the matrix-vector product, Proposition 2.3.1 in Section 2.3, so cv is also in Nul(A).

Since Nul(A) satisfies the three defining properties of a subspace, it is a subspace.

Describe the column space and the null space of

A=(111111).

Solution

The column space is the span of the columns of A:

Col(A)=Span{(111),(111)}=Span{(111)}.

This is a line in R3.

Figure 2.6.10

The null space is the solution set of the homogeneous system Ax=0. To compute this, we need to row reduce A. Its reduced row echelon form is

(110000).

This gives the equation x+y=0, or

{x=−yy=yparametric vector form→(xy)=y(−11).

Hence the null space is Span{(−11)}, which is a line in R2.

Figure 2.6.11

Notice that the column space is a subspace of R3, whereas the null space is a subspace of R2. This is because A has three rows and two columns.

The column space and the null space of a matrix are both subspaces, so they are both spans. The column space of a matrix A is defined to be the span of the columns of A. The null space is defined to be the solution set of Ax=0, so this is a good example of a kind of subspace that we can define without any spanning set in mind. In other words, it is easier to show that the null space is a subspace than to show it is a span—see the proof above. In order to do computations, however, it is usually necessary to find a spanning set.

The null space of a matrix is the solution set of a homogeneous system of equations. For example, the null space of the matrix

A=(172−2134−2−3)

is the solution set of Ax=0, i.e., the solution set of the system of equations

{x+7y+2z=0−2x+y+3z=04x−2y−3z=0.

Conversely, the solution set of any homogeneous system of equations is precisely the null space of the corresponding coefficient matrix.

To find a spanning set for the null space, one has to solve a system of homogeneous equations.

To find a spanning set for Nul(A), compute the parametric vector form of the solutions to the homogeneous equation Ax=0. The vectors attached to the free variables form a spanning set for Nul(A).

Find a spanning set for the null space of the matrix

A=(23−8−5−12−3−8).

Solution

We compute the parametric vector form of the solutions of Ax=0. The reduced row echelon form of A is

(10−1201−2−3).

The free variables are x3 and x4; the parametric form of the solution set is

{x1=x3−2x4x2=2x3+3x4x3=x3x4=x4parametric→vector form(x1x2x3x4)=x3(1210)+x4(−2301).

Therefore,

Nul(A)=Span{(1210),(−2301)}.

Find a spanning set for the null space of the matrix

A=(1324).

Solution

We compute the parametric vector form of the solutions of Ax=0. The reduced row echelon form of A is

(1001).

There are no free variables; hence the only solution of Ax=0 is the trivial solution. In other words,

Nul(A)={0}=Span{0}.

It is natural to define Span{}={0}, so that we can take our spanning set to be empty. This is consistent with the definition of dimension, Definition 2.7.2, in Section 2.7.

Writing a subspace as a column space or a null space

A subspace can be given to you in many different forms. In practice, computations involving subspaces are much easier if your subspace is the column space or null space of a matrix. The simplest example of such a computation is finding a spanning set: a column space is by definition the span of the columns of a matrix, and we showed above how to compute a spanning set for a null space using parametric vector form. For this reason, it is useful to rewrite a subspace as a column space or a null space before trying to answer questions about it.

When asking questions about a subspace, it is usually best to rewrite the subspace as a column space or a null space.

This also applies to the question “is my subset a subspace?” If your subset is a column space or null space of a matrix, then the answer is yes.

Let

V={(ab) in R2|2a=3b}

be the subset of a previous Example 2.6.9. The subset V is exactly the solution set of the homogeneous equation 2x−3y=0. Therefore,

V=Nul(2−3)

In particular, it is a subspace. The reduced row echelon form of (2−3) is (1−3/2), so the parametric form of V is x=3/2y, so the parametric vector form is (xy)=y(3/21), and hence {(3/21)} spans V.

Let V be the plane in R3 defined by

V={(2x+yx−y3x−2y)|x,y are in R}.

Write V as the column space of a matrix.

Solution

Since

(2x+yx−y3x−2y)=x(213)+y(1−1−2),

we notice that V is exactly the span of the vectors

(213)and(1−1−2).

Hence

V=Col(211−13−2).